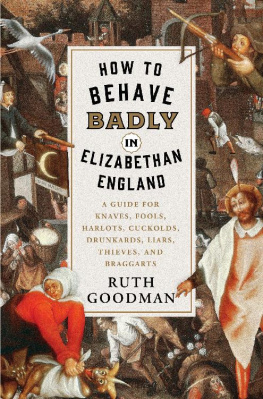

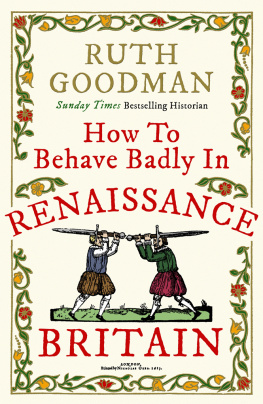

How to Behave Badly in Elizabethan England

A Guide for Knaves, Fools, Harlots, Cuckolds, Drunkards, Liars, Thieves, and Braggarts

Ruth Goodman

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A DIVISION OF W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

CONTENTS

Welcome to a century of bad behaviour. Forget the tales of the great and the good: this is a history of flawed and imperfect people. People whose misdemeanours lead us deeper into their world, as they show us the way that they carved out a life for themselves and reveal some of the thoughts and feelings that made them tick.

For behind the much vaunted gloss of ruffs and shimmering silks, the deeply committed religious reformers, the political visionaries and the great literary figures of the years between 1550 and 1660 lurks the rest of humanity and human experience in all its grubby glory and tarnished glister. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England was a place of vitality, experimentation, expanding horizons and lots of small-minded, petty, badly mannered, irritating and irreverent oiks, guls, gallants and harridans. And I love them all.

Every age and every social stratum has its bad eggs, those who break the rules and rub everyone up the wrong way. People who behave like square pegs in round holes abound in history just as much as in contemporary life. There are people who genuinely dont understand the social conventions of their day, who struggle to follow the subtleties and unwritten rules that govern daily life, and then there are those who deliberately and knowingly flout all codes of conduct. Sometimes the flouters act alone as rebellious individuals, ploughing their own furrow, like Mary Frith who smoked, drank, swaggered and wore mens breeches in public on a regular basis, both shocking and intriguing her fellow citizens. Sometimes people join together in their rule breaking as an act of defiance and seek to forge their own separate group identity, like the idle, arrogant youths of the Damned Crew who drank, fought and bullied their way around the capital, or the holier than thou hotter sort of Protestants, who irritated their neighbours secure in their own sense of superiority. Some navigate their way around and between the rules for their own ends, and others are tossed into transgression by circumstances. The subversion of normal rules can have many causes and many motivations. But the rules are the rules.

Societies in all times and all places are governed by intricate, overlapping codes of conduct. Some of these rules are both open and explicit in the manner of legal pronouncements or formal regulations; others stem from religious beliefs and understandings that can have a more nebulous edge, sliding into the realms of unexplained taboo. Still more grow from allegedly factual interpretations of the world around us that designate certain behaviours right and natural and others perverted and strange. Some have long lost their rationale entirely but persist as part of widely held traditions, rules that demand obedience because we have always done it like that. Many are implied or understood rather than formally spelt out, learnt from the reactions of family, neighbours, colleagues, enemies and friends. They cover every form of social interaction, from hanging out the washing in a communal yard to drinking with mates in the alehouse. The most socially aware and adept individuals can take all these interwoven, and occasionally conflicting, rules and turn them into a seamless performance of confidence and belonging at least some of the time. For historically, just as now, many people struggled to pull it off, to behave perfectly at every encounter and in every situation.

I have a sneaking sympathy for all of them: for the blithely clueless bumbling through the disapproving looks; the acutely embarrassed who would conform if only they knew how; the deliberately curmudgeonly who define themselves by their resistance; the makers of new rules who seek to change the world; the calculating social climbers who pick and choose when to be good and when to be bad; the furiously angry who have gone beyond all care and restraint; the comedians poking fun and the downright mischievous who just cant resist giving the world a little stir.

This is a book for, and about, all of them. It is an exploration of the written and unwritten rules of Tudor and Stuart England, and how people went about breaking them. It is not a history of criminal behaviour as such, although some of the activities in this book will edge into the legally dubious; rather it is a study of all the niggling, antisocial, irritating ways that people used to kick against prevailing social mores. And because the offence and the meaning is all contained within the specific details of these behaviours, you will find, too, within these pages, step-by-step instructions that lay out exactly how to be that annoying and irritating person. We shall rehearse the various ways in which you could embarrass your parents, mock a sober clergyman, disgust your dinner guests and put down your enemies. There are instructions for fighting in various styles so that you can hold your own against the city watch, or at least intimidate the uninitiated into letting you have your way. There are crib sheets of verbal insults outlining the vocabulary but also providing you with a key so that you can extemporize upon certain themes and customize your linguistic attacks to suit the occasion. You will find pointers about sartorial inelegance in several forms that could cause terrible worry to stuffy parents, and also diagrams of rude gestures to assist you in performing them with accuracy for maximum impact. It is a sort of basic tool kit for navigating your way around the edges of society and sliding between the gaps.

And why this particular hundred years? Well, that is very personal. I always have trouble articulating exactly why it is this bit of English history that so captures my attention, heart and soul. But it does, and I cant help but hope that it captures yours, too. I love the combination of the exotically different mingled with the almost familiar, the way you can trace ideas, words, attitudes and habits that at first glance seem so alien as they gently shift into the background of modern life. So much of the twenty-first-century way of life can be illuminated by an understanding of this era. Our current brand of religion and non-religion was shaped at this time. Both the emergence of new forms of worship, the hammering out of new creeds and religious practices and the beginnings of a deep and almost visceral distrust of fundamentalism and overly enthusiastic spiritualism can be found here. Secularism, as well as Quakers and Baptists of various denominations, emerged from these years.

Next page