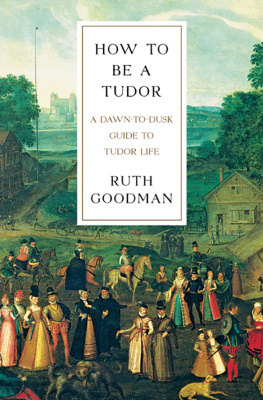

How to Be a Tudor

A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Tudor Life

RUTH GOODMAN

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

To Claire and Geoff Steeley,

who taught me to truly look at the world around me

Contents

Trying to understand the trials and tribulations of ordinary Tudor life has been my passion for the last twenty-five years. There are other periods of history that I have an interest in, but in truth my heart lies somewhere in the middle of Elizabeth Is reign. I am both constantly delighted with the otherness of Tudor thinking and beguiled by the echoes that have slipped through into modern life, from the belief that redheads have hot tempers to the order in which we eat our meals, with starters, mains and desserts to follow. To get the chance to write some of it down and share my love for all things sixteenth-century has therefore been a delight, rather like being let loose in the sweet shop.

The Tudor era is a long and complicated one, encompassing some of the greatest changes in our history, and no book can hope to tell the truth about all the lives lived throughout it. This, then, is necessarily a series of snapshots of the daily realities of some of the people, some of the time, but for all its incompleteness it is still a heartfelt attempt to understand the practicalities, thoughts and difficulties of our forebears.

To set the scene, in 1485 when Henry Tudor seized the throne, there were under two million people in England and perhaps another half a million in Wales (figures for Scotland and Ireland are almost entirely conjectural). By the time his granddaughter Elizabeth I died in 1603, the population of England and Wales combined had doubled to around four million. More than 90 per cent of the population lived in rural areas. London boasted a population of no more than 50,000 at the start of the period but quadrupled in size to 200,000 by the end, and at all times it contained around half of the entire urban population. This small but energetic population was to become a cultural powerhouse whose ideas and way of life were to influence the subsequent history not just of Britain but of the world.

Throughout this book I have used the term Britain as a loose cultural concept, not a political reality. Scotland was an independent nation; Wales was controlled by England throughout the period but the two nations only became legally united in 1536; and English control over Ireland was distant, patchy and fraught. Politically it makes more sense to speak only of England and Wales as an effective power bloc, and when you start to search through the surviving evidence there is a temptation to speak only of England, and southern England at that, where the vast bulk of available information is concentrated. Yet I feel that in much of Wales and at least in some parts of Ireland and indeed Scotland cultural connections and shared ways of life were present, and to write only of England would be quite misleading.

The rural majority were socially organized according to land holdings. The aristocracy at the top of the tree limited to those holding titles as peers of the realm owned several large estates, maintained households of up to 150 people and moved periodically between their houses on each estate and a town house in London. Theirs was a very public life of politics and power. Beneath them sat the gentry, whose land holdings were generally smaller and more concentrated geographically. Officially a gentleman was someone who had the right to a coat of arms, but in practice a gentleman was anyone who lived according to generally accepted standards, engaging in no productive labour, owning and renting out land for others to work, maintaining a suitable-sized house, wearing suitable clothing, and entertaining on a suitable scale. Those who were called gentlemen by their neighbours boasted homes of six or more rooms, had several servants whose main focus was personal and domestic service, dressed in the best woollen broadcloths trimmed with silks and furs, sat down to three or four dishes of meat at dinner, and expected to lead local society and hold public office.

Far more numerous were the yeomen. Their land was often rented from those above them, though many owned portions as well, and they farmed it all themselves. In terms of pure wealth, some were richer than some of the gentlemen, but theirs was a life of active involvement on the land. Most of their servants were not of a personal or domestic nature, but farm servants helping to till the soil and care for livestock. Some did hold junior public positions such as churchwarden or constable, but essentially they were prosperous farmers with four- or five-room houses, good wool clothing and simple but hearty dinners.

Next came the husbandmen, farming their rented lands on a much smaller scale. Their homes were generally two-room affairs and most of the labour came purely from within the family. They were the most numerous of all the groups and their lives held precious few luxuries.

Below them were the labourers who held no land at all but had to hire themselves out to their socially superior neighbours for a daily wage. As our period moves forward, their numbers gradually grew as husbandmen increasingly struggled to maintain an independent hold on the land and joined their ranks. It was a precarious life and one generally lived in single-room dwellings with a diet dominated by bread and little else.

For our tiny urban population the hierarchy was a little different, with international merchants occupying the top spots, serving as mayors, living in large, well-furnished and well-staffed town houses, occasionally hobnobbing with the landed elite. Other merchants formed the next layer down, employing apprentices and servants and living a life that was a little more comfortable, but of a similar social level to that of yeomen. Craftsmen occupied the next slot, aided by their apprentices and family, with typically one or two rooms in addition to a workshop. And, just as in the countryside, the bottom of the pile consisted of labourers paid by the day.

The Tudor economy was essentially a money economy, barter being no more common than in our own times, but what it could buy was fundamentally different. Within a twenty-first-century household, food costs consume typically around 17 per cent of the total income, but within a Tudor context food dominated most peoples expenses, taking around 80 per cent. To understand what money meant to a craftsman contemplating a new coat, it is necessary to think more in terms of disposable income, what was left once the family were fed and the rent paid. For a husbandmans wife, the decision whether to buy in ale, make it herself or let the family make do with water was one that required weighing one set of monetary needs against another, with the margins tipping the balance. At the start of our period a skilled man could command a wage of 4d a day when he was in work, and women could bring in about half that. By the end of the era a skilled wage was more usually 6d. These figures represented the basic survival level for a small family in regular work, enough to eat a plain, cheap diet, but not much more. It is against this subsistence level of financial resources that prices and resources can be gauged.

This then was the structure within which people had to negotiate a livelihood and find a sense of self.

There are many books and studies based on the lives of the Tudor elite, upon the powerful and well-documented, but my interest has always been bound up with the more humble sections of society. As a fairly ordinary person myself who needs to eat, sleep and change the occasional nappy, I wanted from the beginning to know how people coped day to day, to know what resources they really had at their disposal, what skills they needed to acquire and what it all felt like. Twenty-five years ago I could find no book to tell me, and even now when social history receives far more academic attention than before, information is still thin on the ground. So I set out to try and work it out for myself: hunting up period recipes and trying them out; learning to manage fires and skin rabbits; standing on one foot with a dance manual in one hand, trying to make sense of where my next move should be. The more I experimented, the more information I began to find within the period texts that I was looking at. Things that I had just skimmed past in the reading became quite critical in practice, prompting more questions and very much more intense research. Many repeated statements about Tudor life, quoted in very respectable works, turned out to be pure fantasy.

Next page