PRAISE FOR HOW TO BEHAVE BADLY IN RENAISSANCE BRITAIN

Impeccable [Goodmans] research is as comprehensive as the advice she metes out to those wishing to emulate the bad behaviour of their ancestors.

Tracy Borman, BBC History Magazine

This is a masterclass of bad behaviour a lively romp through early modern British social history.

Who Do You Think You Are? magazine

Entertaining.

History Revealed magazine

PRAISE FOR HOW TO BE A TUDOR

This book is packed with delicious kernels of knowledge all served up by the most delightfully eccentric author Ive ever encountered.

The Times

Always entertaining, and her narrative is often lifted by the fact that she has taken the trouble to experience many of the alien aspects of Tudor life.

Observer

Goodmans latest foray into immersive history is a revelation Its the next best thing to being there.

New York Times Book Review

A deeply researched and endlessly fascinating account of what it was like to live as a Tudor. The narrative is rich in period detail and based upon a thorough review of the contemporary sources, but what makes it unique is the fact that Goodman has put it all into practice sleeping, eating, washing and dressing like a Tudor. [It] is one of very few books which can justifiably claim to bring every aspect of this enduringly popular period dazzlingly to life.

Tracy Borman

[Goodmans] enthusiasm is exhilarating and contagious.

Kate Tuttle, Boston Globe

Riveting. This is a real peoples history that takes us straight into the sensate feelings of ordinary life the feel, touch, smells and labour of people living five centuries ago, giving an earthy reality to our enduring fascination with the Tudors.

Juliet Gardiner

PRAISE FOR HOW TO BE A VICTORIAN

I absolutely love this book. Exuberant, absorbing.

A. N. Wilson, Mail on Sunday

Ruth a woman who possesses so much elbow grease that she could probably can the overflow to sell on the side.

Independent

Written with such passion that one cannot help but be carried along Will fascinate and inform anyone who is in any way interested in Victorian ways of life.

Ian Mortimer

Makes you feel as if you could pass as a native.

New Yorker

If the past is a foreign country because they do things differently there, were lucky to have such a knowledgeable cicerone as Ruth Goodman.

Wall Street Journal

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Ruth Goodman 2020

Ruth Goodman asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-782438-50-2 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-782438-53-3 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publisher, so that full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

To all those who have ever swept the ashes from a hearth

CONTENTS

Lived History

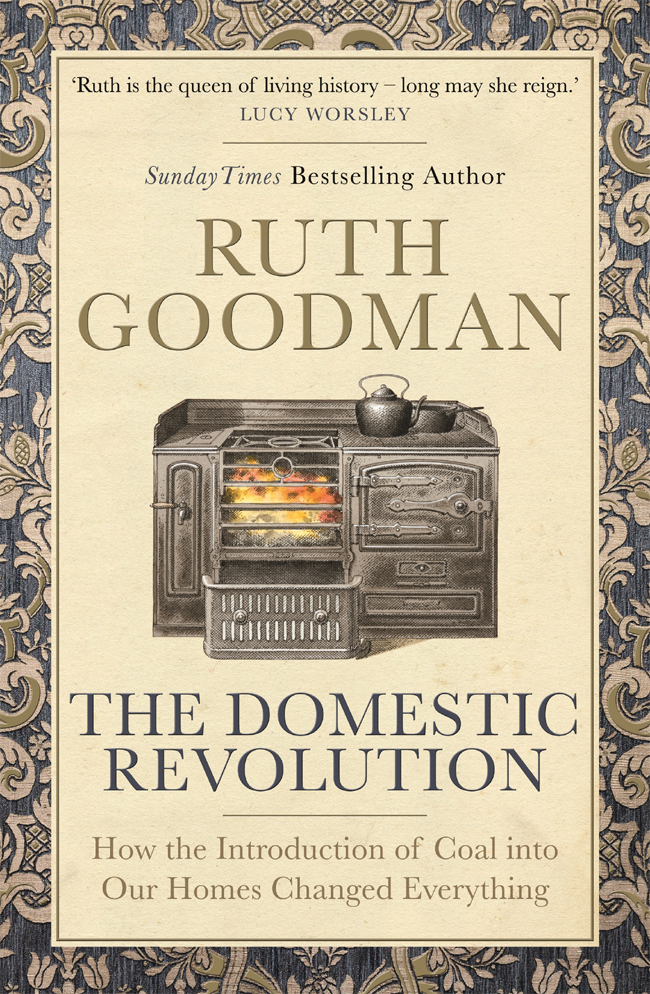

About ten years ago, for the purpose of making a TV programme, I found myself standing in front of a newly refitted coal-fired iron range. It was part of a semi-derelict cottage into which wed already put a huge amount of work rebuilding a staircase, replastering walls, renewing windows and doors, and re-laying a floor. We then inserted a salvaged range, giving it a thorough overhaul before gently easing it into its new home. Brickwork was adjusted around it, then all the gaps were sealed. We gathered round as the first fire was lit and became a tad overexcited when smoke began issuing from the chimney, with barely a wisp visible in the kitchen.

The programme we were making required me and my two colleagues to run a small farm for a year in the manner typical of British people in the second half of the nineteenth century. As the woman on the team, and following on from Victorian practice, this black metal box and its dirty black fuel were to be my responsibility. I had never cooked on coal before. I did, however, have a great deal of experience working with wood fires, including for a previous TV series that had run for a year, as well as twenty years worth of weekends and short breaks in various structures and open spaces. I felt fairly confident that a coal range would be well within my capabilities. Well, I managed it but the encounter was much more challenging and interesting than I had anticipated. And it was one that encompassed much more than cooking.

The radically different practices involved in running a coal-fired home in comparison to running a wood-fired one took me completely by surprise. So many things that I had taken for granted suddenly became immediate and pressing issues. The challenges that I was facing, and the adjustments I was having to make as I learnt to deal with coal, were wide-reaching. When I considered the impact such changes must have had, when multiplied by the number of households that had made these changes in the past, it was mind-boggling. I began to realize that the usual narratives about the development of the home, the countryside and the modern industrial world were missing something: the big switch to domestic coal in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

In many ways I was in a highly unusual position. Most people experimenting with the use of coal as a fuel are approaching the problem from a modern perspective, making comparisons with gas and electricity. Our attitudes and assumptions are necessarily backwards-looking. But much of my experience came from older technologies; I have probably cooked more meals over a wood fire than I have over gas or electric cookers. I have certainly cleaned more houses heated by open wood fires than those with central heating, and long ago adapted my laundry regime to something inspired by earlier methods. My engagement with the great outdoors was almost entirely framed by historical experiment and experience, with weekends spent felling trees with axes and cross-cut saws, coppicing patches of woodland, building period styles of fencing and growing heirloom plants. Looking at the world through wood-burning eyes was second nature to me. From this vantage, it was obvious to me that the switch to coal would have had a huge impact on the daily routines of people from all walks of life.

I first became aware that some of the practical skills I was learning could genuinely form a useful addition to the scholarly understanding of this history when I was invited to help out some twenty years ago at the Mary Rose Trust. This charity is charged with caring for the archaeological remains of Henry VIIIs flagship, which sank as he watched from the shore in the strait between the Isle of Wight and the English mainland on 19 July 1545. The excavation of the flagships remains had revealed two brick structures sitting upon some loose gravel ballast at the ships bottom, on either side of the central keel beam. These were assumed to be the galleys. However, when the ship reached the seabed upon that fateful day nearly five hundred years ago, it had tipped over onto one side, sending one of the two galley structures crashing over on top of the other. The excavations had thus mostly uncovered a mass of rubble. The trust had launched a project to reconstruct the cooking facilities and provide a better picture of life on board a mid-Tudor warship.

Next page