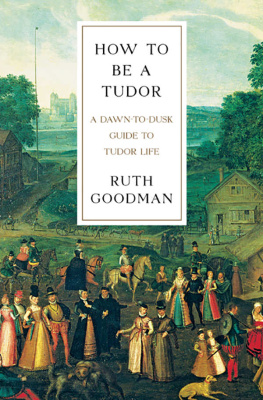

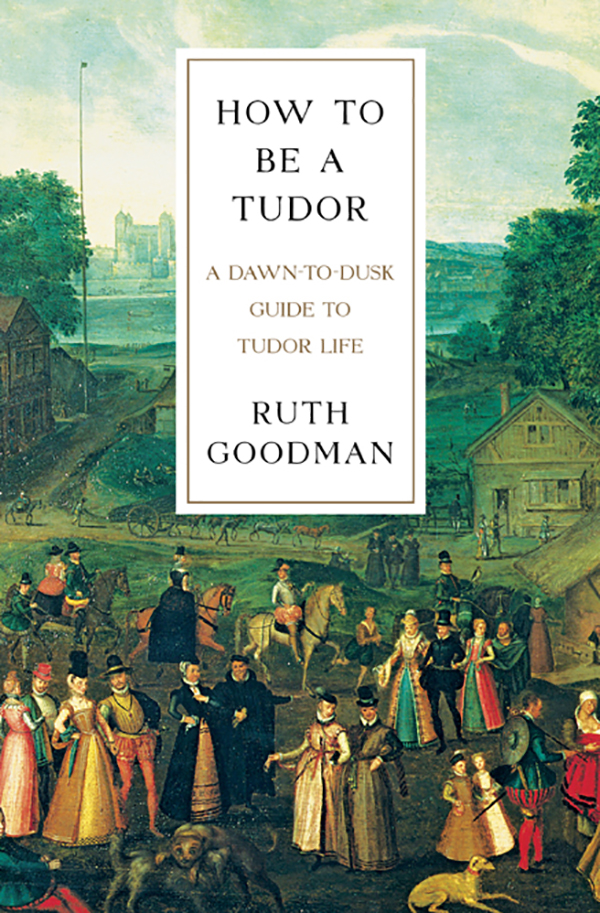

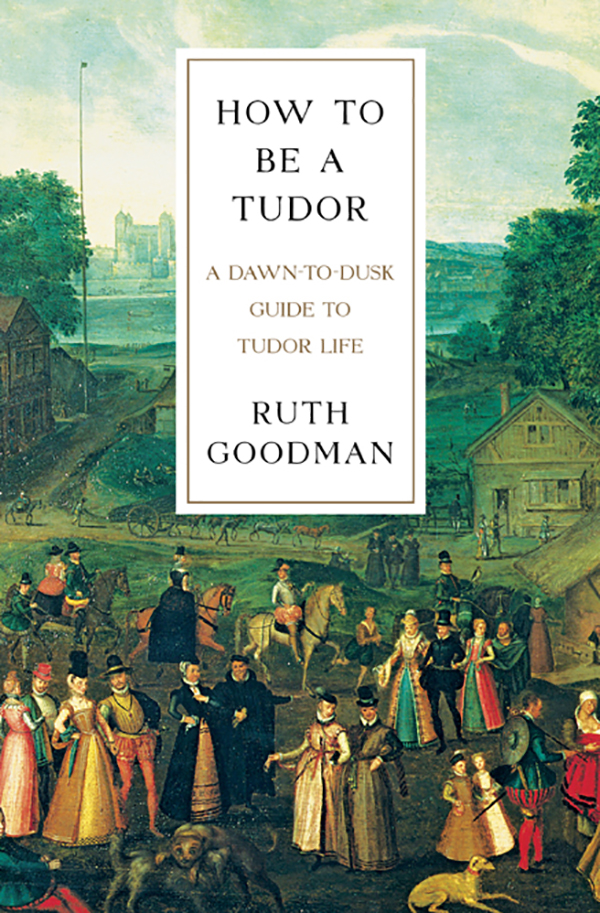

How to Be a Tudor

A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Tudor Life

RUTH GOODMAN

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

Exploring the Tudor world has not been a solo activity, but rather one shared with friends, colleagues and family, and I owe them an enormous debt. First and foremost my husband, who first introduced me to living history and has journeyed with me in more depth ever since. Also my daughter, who was co-opted from five weeks of age before eventually spreading her wings and finding her own historical interests. I would also like to thank Andy Munro, Shona Rutherford and Joan Garlick for those first excursions into Tudor food and Tudor dance. Over the years Dr Eleanor Lowe, Jackie Warren, Karl Robinson, Natalie Stewart and Jon Emmett have been especially helpful, both intellectually and experimentally. Many of the thoughts, ideas and inspirations behind this book come from them. Hugh Beamish, Paul Hargreaves, Kath Adams, Sigrid Holmwood, Paul Binns, Cathy Flower-Bond, Hannah Miller, Sarah Juniper and Jennifer Worrall have all pointed me in new and interesting directions, for which they have my profound gratitude.

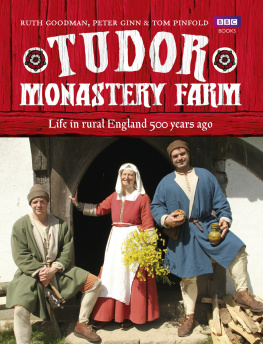

I should also like to extend my thanks to my colleagues within the television industry who have shared and sometimes endured Tudor experiences with me, particularly Peter Ginn, Stuart Elliott, Tim Hodge, Georgina Stewart, Giulia Clark, Tom Pilbeam, Sarah Laker, Felicia Gold, Tom Pinfold and Will Fewkes.

I owe another debt to Jenny Tiramani, Mark Rylance, all the wardrobe, props and other staff and the actors at the Globe Theatre who shared a passion for uncovering the practical realities of Elizabethan theatre and incidentally taught me to love both theatre and Shakespeare.

My thanks too to the staff at the V&A and the Museum of London for access to and discussion about their textile collections. The County Record Offices of Buckinghamshire, Essex, Cheshire and Devon have been generous with both their time and their expertise. Several museums have also allowed me to use their buildings, grounds and collections to experiment and practise different aspects of Tudor Life, adding their own thoughts and interpretations. My thanks extend to The Weald and Downland Museum in West Sussex, St Fagans Museum of Welsh Folk Life in South Wales, Haddon Hall in Derbyshire, the Mary Rose Trust in Portsmouth, the Chiltern Open Air Museum in Buckinghamshire, the National Trust, English Heritage, and Rufford Country Park in Nottinghamshire.

I am indebted to my wonderful editors at Penguin, without whose work this book would be riddled with far more errors than it is (all of which of course are my own, not theirs).

Lastly, I would like to thank the myriad of historical re-enactors, museum staff, volunteers and students that I have worked alongside whose enthusiasm, willingness to get mucky and open-mindedness have made the last twenty-five years so much fun.

By the same author

How to Be a Victorian

Victorian Farm (with Alex Langlands & Peter Ginn)

Edwardian Farm (with Alex Langlands & Peter Ginn)

Wartime Farm (with Alex Langlands & Peter Ginn)

Tudor Monastery Farm (with Peter Ginn & Tom Pinfold)

To Claire and Geoff Steeley,

who taught me to truly look at the world around me

Copyright 2015 by Ruth Goodman

First American Edition 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Books, under the

title How to be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Everyday Life

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

ISBN 978-1-63149-139-9

ISBN 978-1-63149-140-5 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Trying to understand the trials and tribulations of ordinary Tudor life has been my passion for the last twenty-five years. There are other periods of history that I have an interest in, but in truth my heart lies somewhere in the middle of Elizabeth Is reign. I am both constantly delighted with the otherness of Tudor thinking and beguiled by the echoes that have slipped through into modern life, from the belief that redheads have hot tempers to the order in which we eat our meals, with starters, mains and desserts to follow. To get the chance to write some of it down and share my love for all things sixteenth-century has therefore been a delight, rather like being let loose in the sweet shop.

The Tudor era is a long and complicated one, encompassing some of the greatest changes in our history, and no book can hope to tell the truth about all the lives lived throughout it. This, then, is necessarily a series of snapshots of the daily realities of some of the people, some of the time, but for all its incompleteness it is still a heartfelt attempt to understand the practicalities, thoughts and difficulties of our forebears.

To set the scene, in 1485 when Henry Tudor seized the throne, there were under two million people in England and perhaps another half a million in Wales (figures for Scotland and Ireland are almost entirely conjectural). By the time his granddaughter Elizabeth I died in 1603, the population of England and Wales combined had doubled to around four million. More than 90 per cent of the population lived in rural areas. London boasted a population of no more than 50,000 at the start of the period but quadrupled in size to 200,000 by the end, and at all times it contained around half of the entire urban population. This small but energetic population was to become a cultural powerhouse whose ideas and way of life were to influence the subsequent history not just of Britain but of the world.

Throughout this book I have used the term Britain as a loose cultural concept, not a political reality. Scotland was an independent nation; Wales was controlled by England throughout the period but the two nations only became legally united in 1536; and English control over Ireland was distant, patchy and fraught. Politically it makes more sense to speak only of England and Wales as an effective power bloc, and when you start to search through the surviving evidence there is a temptation to speak only of England, and southern England at that, where the vast bulk of available information is concentrated. Yet I feel that in much of Wales and at least in some parts of Ireland and indeed Scotland cultural connections and shared ways of life were present, and to write only of England would be quite misleading.

The rural majority were socially organized according to land holdings. The aristocracy at the top of the tree limited to those holding titles as peers of the realm owned several large estates, maintained households of up to 150 people and moved periodically between their houses on each estate and a town house in London. Theirs was a very public life of politics and power. Beneath them sat the gentry, whose land holdings were generally smaller and more concentrated geographically. Officially a gentleman was someone who had the right to a coat of arms, but in practice a gentleman was anyone who lived according to generally accepted standards, engaging in no productive labour, owning and renting out land for others to work, maintaining a suitable-sized house, wearing suitable clothing, and entertaining on a suitable scale. Those who were called gentlemen by their neighbours boasted homes of six or more rooms, had several servants whose main focus was personal and domestic service, dressed in the best woollen broadcloths trimmed with silks and furs, sat down to three or four dishes of meat at dinner, and expected to lead local society and hold public office.

Next page