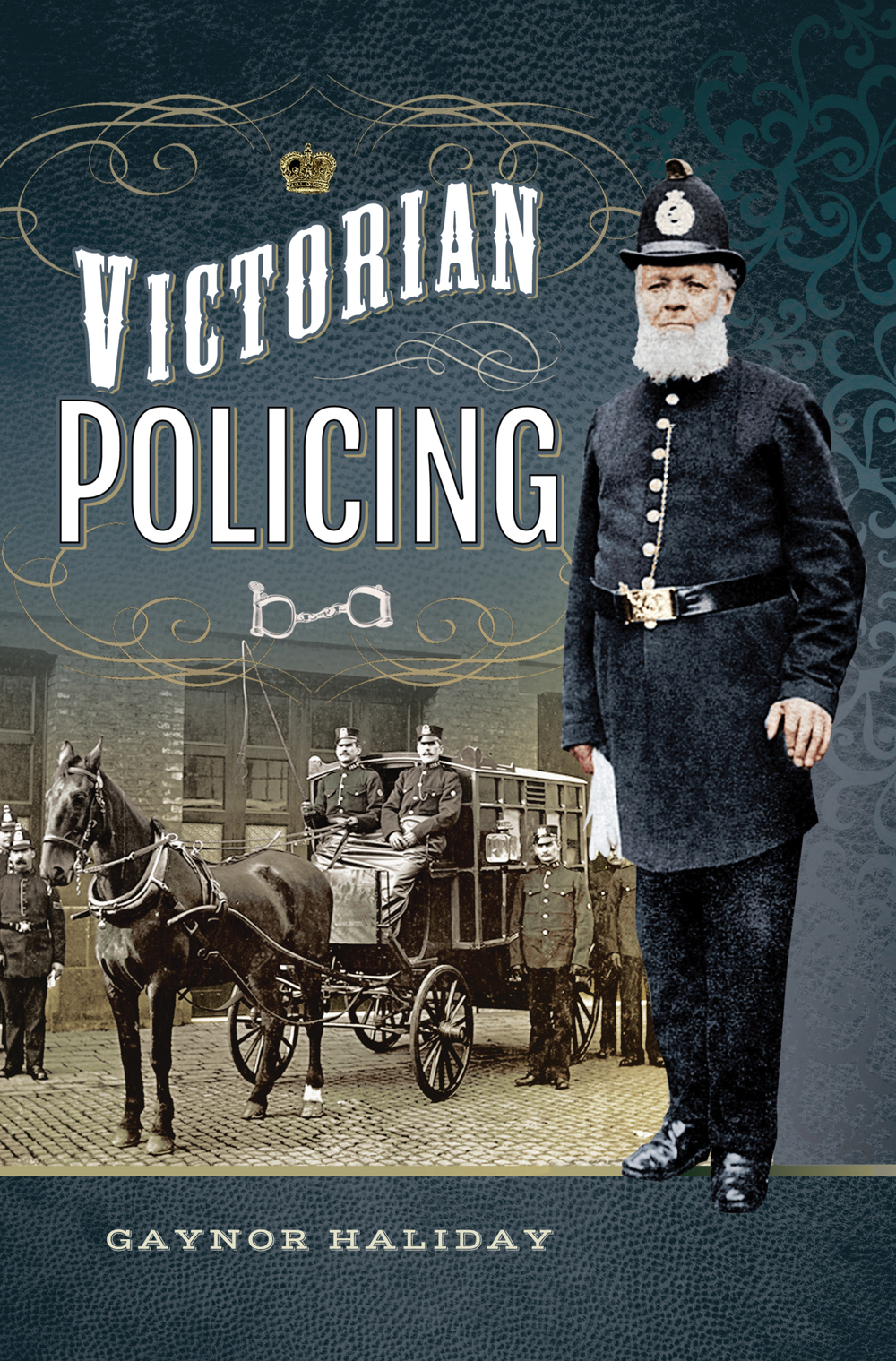

Victorian Policing

Gaynor Haliday

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Gaynor Haliday, 2017

ISBN 978 1 52670 612 6

eISBN 978 1 52670 614 0

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 613 3

The right of Gaynor Haliday to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Foreword

My interest in Victorian policing started when researching my great-great-grandfather, Thomas Bottomley, who had served in Bradford Borough Police Force in the nineteenth century.

PC Thomas Bottomley was one of fifty-eight Bradford street characters whose portraits were painted by professional watercolour artist John Sowden in the 1880s and 1890s. These included colourful personalities, such as Old Betty, Salt Jim, Pot Mary, Fish David and Cheap John, who made their livings as street musicians, or by hawking and peddling all sorts of merchandise as fruit, fish or flower vendors, and were very visible on the Victorian streets. Although the portraits included blind and crippled beggars, only those who were respectable were invited to sit for Sowden at his studio.

Why my great-great-grandfather was among these individuals is somewhat a mystery. Sowden made scant diary notes about his sitters, and his notes on Thomas Bottomley in 1889 merely tell of his quiet, sensitive policing, and rumour that he never had a case reach the courts in thirty years.

Finding Thomass records and learning that he had left his work as a woolcomber to join the police in February 1852, been superannuated in April 1891, and only once been reprimanded yet never progressed beyond the rank of constable, made me keen to discover more.

Many of the Manningham streets where he walked his beat still exist. Two of his former homes also stand. The ornate police station, once his base, remains though in a state of disrepair. With these visible reminders of his life it was easy to conjure up a picture of him, a well-respected peace-keeper, calmly walking about on paved and well-lit streets, sending the odd drunk home to his wife and bairns, and, seeing all was in order, going home to his large family for tea.

Of course, as I discovered, nothing could be further from the truth. Contemporary newspaper accounts revealed PC Thomas Bottomley made many arrests, encountered violent criminals, and was frequently assaulted in the dark and grimy Bradford streets. But despite these tribulations he remained a local beat constable for thirty-nine years an astonishing length of service considering how many others resigned or were dismissed after a very short period. Perhaps that is what earned him a place in the Bradford street characters history, and grudging respect from the criminal fraternity who nick-named him Old Bott.

Victorian Policing explores the lives of the courageous pioneers of policing, who worked long hours with little resource, without the assistance of later developments in technology, and with few rest days.

Coming from a wide range of backgrounds, they had little education or training to handle the roles demanded of them, yet many of the crimes and human issues they dealt with, and the hostility they encountered in doing so, were not dissimilar to those experienced by todays police forces.

The newspaper accounts of the time carried myriad reports of police activities some amusing, some heroic, some tragic. I have tried to include pertinent examples to illustrate what working life was really like for the nineteenth-century bobby on the beat.

I would particularly like to thank the following for their assistance in my research: Staff at West Yorkshire Archive Service (WYAS) for extracting the huge watch committee tomes and other records from the archives. Duncan Broady, Curator, Greater Manchester Police Museum and Archives for his help in their archives, allowing me to photograph accoutrements and documents, and for bringing items to my attention that I would otherwise never have known about. Lisa Marks, Corporate Communications Branch, Greater Manchester Police, for providing many images. Dr Martin Baines QPM and Margaret Gray, of Bradford Police Museum, for assistance and image of PC Bottomley. Pete Simpson, Cambridgeshire Police Museum for images. Holly Wells, Kent Police History Museum for images. Ross Mather, The British Police Helmet website creator, and former curator of the South Wales Police Museum.

Chapter 1

Laying the foundations

We sometimes imagine our ancestors living tough but peaceable lives working hard in the fields, the worst disturbances being a few petty squabbles. A bucolic way of life where a police force was not required. But human nature has occasionally led some people to covet what others have property, land, belongings, spouses and for that reason policing in one form or another has always been necessary to try to keep the peace, deter the criminal fraternity and bring those who disobey the law to justice.

The concept of formal policing was introduced as early as 1285, when the Statute of Winchester instituted a system of watch and ward, putting in place a structure of watchmen, specifying the number of men, according to a towns population, who were to keep watch from dusk to dawn. Their key duty was to arrest any passing strangers, hold them until morning and deliver suspicious characters to the sheriff to be dealt with. These watchmen were obliged to raise the hue and cry and pursue from town to town any stranger who resisted arrest until he was caught. All able-bodied men were to assist in the chase.

Apart from this, it was up to local residents to maintain a modicum of law and order. Under the statute every man between the ages of 15 and 60 was commanded to house equipment to keep the peace, according to the quantity of land and goods he possessed.

The richest were expected to keep a horse, lance, knife, iron helmet and a long coat of chain mail known as a hauberk, while the poorest carried just bows and arrows. Each mans armoury was inspected twice a year by two high constables appointed for each hundred (a division of a county for military and judicial purposes). These high constables reported any defaults of the equipment or of the watchmen, as well as reporting those in country towns who lodged strangers, and any faults in the highway, to the assigned justices, who in turn reported the matter to the king.

Further to this, the Justices of the Peace Act in 1361 instilled the principle of a working partnership between justices and constables and, by appointing people to prosecute felonies and trespasses, established statutory powers for justices of the peace.

Next page