The following artists and scientists have influenced the forming of the ideas in this book: Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Drer, Paul Czanne, Jackson Pollock, DArcy Wentworth Thompson, Wilhelm Reich, Louis Sullivan, Theodore Schwenk, Ernest Lehrs, Hermann Poppelbaum, and my friends of many yearsRobert McCullough, biologist, and Richard Snibbe, architect.

Those who have helped to bring this book to print are Donald Holden, Editorial Director of Watson-Guptill; Juliana Goldman, editor; Anna Walters, typist; Mrs. Alison B. Hale, my helpmate; and my students.

Bibliography

Boon, K. G. Rembrandt: The Complete Etchings.

New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963.

Cirker, Blanche, ed. Eighteen Hundred Woodcuts by Thomas Bewick and His School.

New York: Dover Press, 1962.

Cole, Rex V. The Artistic Anatomy of Trees: Their Structure and Treatment in Painting.

New York: Dover Press, 1951.

Cole, Rex V. Perspective: The Practice and Theory of Perspective as Applied to Pictures.

New York: Dover Press, 1970.

Ferrari, E. L., ed. Goya: His Complete Etchings, Aquatints, and Lithographs.

New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1962.

Gudiol, J., ed. Goya.

New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1965.

Hale, Robert B. Drawing Lessons from the Great Masters.

New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1964.

Kepes, Gyorgy. Language of Vision.

Chicago, Illinois: Paul Theobald, 1945.

Kepes, Gyorgy, ed. Vision and Value (Series)

New York: George Braziller, 1966.

Kurth, Willi. Complete Woodcuts of Albrecht Drer.

New York: Dover Press, 1963.

Lanteri, E. Modelling and Sculpture: A Guide for Artists and Students.

New York: Dover Press, 1965.

MacCurdy, Edward, ed. The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci.

New York: George Braziller, 1955.

Petrides, George A. Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs.

Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, 1958

Poppelbaum, Hermann. Man and Animal.

London: Anthroposophic Press, 1932

Pough, Frederick H. Field Guide to Rocks and Minerals.

Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, 1953.

Reich, Wilhelm. Character Analysis.

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1949.

Reich, Wilhelm. Cosmic Superimposition.

New York: Orgone Institute Press, 1951

Reich, Wilhelm. Ether, God and Devil.

New York: Orgone Institute Press, 1949.

Richter, Jean Paul. The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci.

New York: Dover Press, 1970.

Schindler, Maria. Goethes Theory of Color.

London: New Culture Publications, 1946.

Schwenk, Theodore. Sensitive Chaos.

New York: Rudolph Steiner Publications, 1965.

Sullivan, Louis H. System of Architectural Ornament According with a Philosophy of Mans Powers.

New York: Eakins Press, 1967.

Thompson, DArcy Wentworth. On Growth and Form.

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 1961

White, Christopher. Drer: The Artist and His Drawings.

New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1971

Paperbound unless otherwise indicated. Available at your book dealer, online at www.doverpublications.com, or by writing to Dept. 23, Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, NY 11501. For current price information or for free catalogs (please indicate field of interest), write to Dover Publications or log on to www.doverpublications.com and see every Dover book in print. Each year Dover publishes over 500 books on fine art, music, crafts and needlework, antiques, languages, literature, childrens books, chess, cookery, nature, anthropology, science, mathematics, and other areas.

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

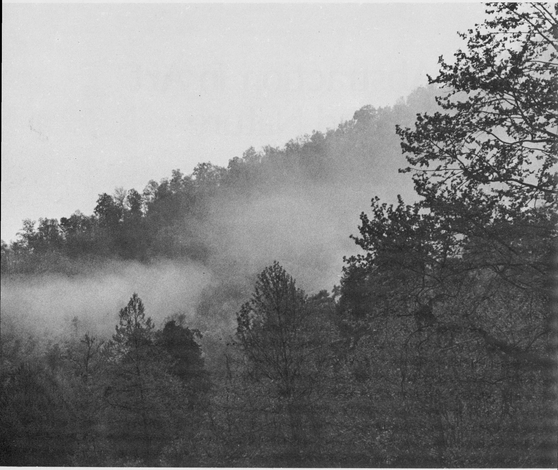

This view of the Cumberland Mountains in Kentucky in early morning would be taken for granted by many people. But to the artist, many things are revealed: the age of the mountains and the direction of the thrust of their strata, the lines of erosion in relation to the plane of gravity, and the lines of levitation in the upward thrust of the trees and plants. In the swirls of the mist of fog, the artist can see the spinning wave movements that animate all nature.

1. The Meaning of Abstraction

The biggest challenge to the artist in the twentieth century is learning the abstract language of art. Long ago it was enough to copy the surface forms of nature, but now it is our task to get to the root of natures meanings. There is no other way to do this than to learn the kind of reasoning that enables us to look beneath the surface of things. The artists of our time are attempting to learn and develop this kind of insight. Not all of their experiments have been successful; some have led the creators into corridors from which there is no outlet.

In the general confusion of twentieth-century styles, it has been difficult for the average person to understand the art of our time; but it is far more difficult for the artist and art student because their careers demand that they find their own path through the chaos. We are faced with so many different schools of thought and conflicting points of view that we overlook the meaning of the word abstraction which simply means the act of drawing out the essential qualities in a thing, a series of things, or a situation.

EVOLUTION OF ABSTRACTION

This book is intended as a guide to help you through the maze of abstract schools to the simple problems of abstraction. Whether you are an art student or an artist learning on your own, this text will help you to grasp the fundamentals of the abstract language of art. It may seem boastful for me to claim that this book will make the problems of abstraction clear. But the answers to these problems are accessible to anyone who takes the time to do a little detective work and to follow the clues that can be found in nature and in the art of the past.

We must try to step aside from the confusion of schools, movements, and current fads, and attempt to see the whole story of art as a meaningful effort of mankind. This confusion is particularly damaging when it happens in the art schools because the pressure of having to choose sides narrows the students point of view, rather than enlarging it. Being forced to make such a choice prevents the student from exploring and freely selecting the kind of expression that is closest to his heart, his character, or his talents. In this book, I hope to avoid this kind of narrowness. Although, as a working artist, I may follow a certain paththe path that is best for me! hope this book will encourage you to find the one that is best for you. Art is a product of evolutionnot often a result of revolutiona product of the meaningful insights accumulated by artists over thousands of years. Fortunately, these insights cannot be easily erased; they continue to endure and they eventually modify and absorb the useful products of revolution.

The language of the abstract elements of art has developed graduallyas mankind has developed. This language is by no means a product of the twentieth century alone. Over thirty thousand years, each of the seven abstract elements of art in Western civilization has emerged to become part of our cultural treasury. These elements are (1) line, (2) shape-form-mass, (3) pattern, (4) scale-proportion-space, (5) analysis-dissection, (6) lightness-darkness, and (7) color. When we understand the amount of time it has taken to build these seven elements, we can begin to value them as a hard-won heritage.