To Joan, for seeing light even in the darkest of places

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

Visit our website at www.papress.com.

2014 Traer Scott

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright.

Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Sara E. Stemen

Designer: Jan Haux

Special thanks to: Meredith Baber, Sara Bader, Nicola Bednarek Brower, Janet Behning, Megan Carey, Carina Cha, Andrea Chlad, Barbara Darko, Benjamin English, Russell Fernandez, Will Foster, Jan Cigliano Hartman, Diane Levinson, Jennifer Lippert, Katharine Myers, Jaime Nelson, Jay Sacher, Rob Shaeffer, Marielle Suba, Kaymar Thomas, Paul Wagner, and Joseph Weston of Princeton Architectural Press

Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

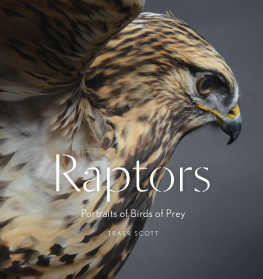

Scott, Traer.

Nocturne : creatures of the night / Traer Scott.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61689-288-3 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-61689-353-8 (epub, mobi)

1. Nocturnal animals. I. Title. II. Title: Creatures of the night.

QL755.5.S36 2014

591.518dc23

2014006210

Into the darkness they go, the wise and the lovely.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Introduction

M y journey into darkness began with visions of brilliantly colored, powdery wings beating softly through the warm night sky. Moths: the mysterious, moonlit cousins of the perky, sunny butterflyflitting wildly and ever frantically near our porch lights but never coming quite close enough to be truly illuminated. One summer evening it suddenly occurred to me how wonderful it would be to do a photographic series about them. There are more than 160,000 different moth species; I could name maybe two, but there are myriad splendid, exotic, even somewhat frightening varieties. An Internet search revealed moths with bright-green wings, moths with astoundingly intricate geometric patterns, and moths with markings so delicate they could have been painted with a feather. The moths eventually led me to ideas about transformation and nightfall, to predators and prey, and then to the bats who eat mothsand then I had it. The idea for Nocturne was hatched, rather appropriately, just after midnight.

In the coming weeks I feverishly researched the roster of nocturnal animals and then began approaching friends and colleagues, who set me up with my first subjects. It is important to note that a great many of the creatures in this book were injured or orphaned wild animals who would never be able to survive in nature. Both of the cougars, for example, were stranded as cubs after their respective mothers were shot by hunters. The great horned owl was hit by a car and has a permanent wing injury. One of the servals has only three legs. By living their lives in semipublic these rescued animals serve as wildlife ambassadors, giving children, in particular, a chance to connect with an animal that they would probably never otherwise see up close, a chance to be inspired to care about wildlife.

Photographers are observers and documentarians, but we are also interlopers, dabbling in lives and milieus that provoke our curiosity but are not ours. In making this book I worked with wildlife rehabilitation centers, educational facilities, and conservation-oriented zoos. The keepers, nurturers, and educators whom I met were filled with passion and knowledge about their animals and utterly dedicated to their well-being. I got to slip in the back door, meet their fascinating charges, and witness the devotion that drives their lives.

While photographing Nocturne I had the opportunity in a few instances to play the role of both observer and nurturer. The beautiful moths that were my very first subjects were obtained as cocoons from scientific supply companies and raised by my family. Studying or photographing large moths is close to impossible unless you hatch them yourself, because their indigenous territories are limited, they are nocturnal, and their lives are extremely brief.

Luna moths, for example, live for only a few days, during which time they dont eat or drink; in fact, they have no mouths. Their sole function during their brief existence is to find a mate and ensure future generations of moths. A romantic friend of mine, touched by their tragically short existence, insists that luna moths live for love, and I suppose, in a way, they do: they live for the love of persistence and evolution.

Luna moths eclose (that is, emerge from their cocoons) in midmorning and immediately scurry up whatever is available; hang upside down; and allow their tiny, crumpled wings to slowly fill with blood. After a few hours the new, bright-green wings will have unfolded, and the moth will begin to dry them by pumping them back and forth a little. Then the moth will rest until nighttime. Luna moths in the wild fly only at night; once the sun sets, the moth will take off in search of a mate. The male hunts doggedly for his female, following hints and trails of scent until he finds her. Female moths emit pheromones at night, which a male moths bushy antennae can detect from several miles away. Mating generally occurs just after midnight, and when the act is complete, the female will lay her eggs on a host plant, often on the underside of a black walnut leaf. Both she and her mate will die shortly after.

I felt very beholden to these fragile and beautiful little creatures that we brought into the world and wanted to make their fleeting lives fulfilling in some way. The dilemma of hatching moths is that if you release one alone, it stands very little chance of finding a mate, but if you wait until all of your cocoons have hatched, in the hope of releasing them together, they may not all survive long enough to be released. So I released my moths incrementally, always in the exact same spot: on a nice, leafy hardwood at the edge of a park full of deciduous trees, near the ocean. Each moth would eclose in the morning; I would photograph it during the day and then release it at sundown. I felt that if they werent going to be able to achieve their mating destiny, the moths should at least be allowed to fly and feel the cool summer night air.

One night, while attempting to guide a sluggish moth to freedom, I spied bats flying overhead and hoped that they would not spot my moth. Little brown bats are quite common in our area. In fact, the previous year, we had one who decided to hang out in our living room after becoming disoriented and flying in through an open window. My husband and I were able to carefully catch him in a towel and send him hurrying off into the night, but many people have no idea what to do when they find a bat in their house. The fear of rabies throws otherwise sane people into an instant panic, even though modern studies prove that a very small percentage of bats actually carry the disease. Still, even when you are armed with that knowledge, seeing a wild bat flying near your sleeping infant, as we did, is a little scary.

In our state it is illegal to kill bats, yet the city does not provide any sort of removal program for them or any other animal deemed nuisance wildlife. Generally people end up calling private wildlife removal services that charge exorbitant fees. These often promise humane removal, but in many cases if the bat is actually caught rather than convinced to relocate, it is euthanized. If a human or household pet has been bitten, the bat must be killed to test for rabies. The bottom line is that most people dont want bats near their family and will do whatever is necessary to get rid of them, which is unfortunate.

Next page