For my sweet Agatha, who is just a little bit wild.

Copyright 2016 by Traer Scott.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 9781452141077 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

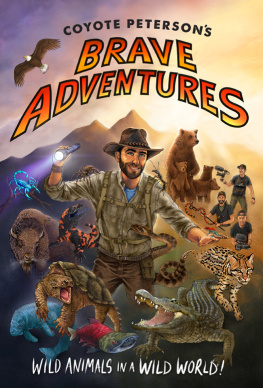

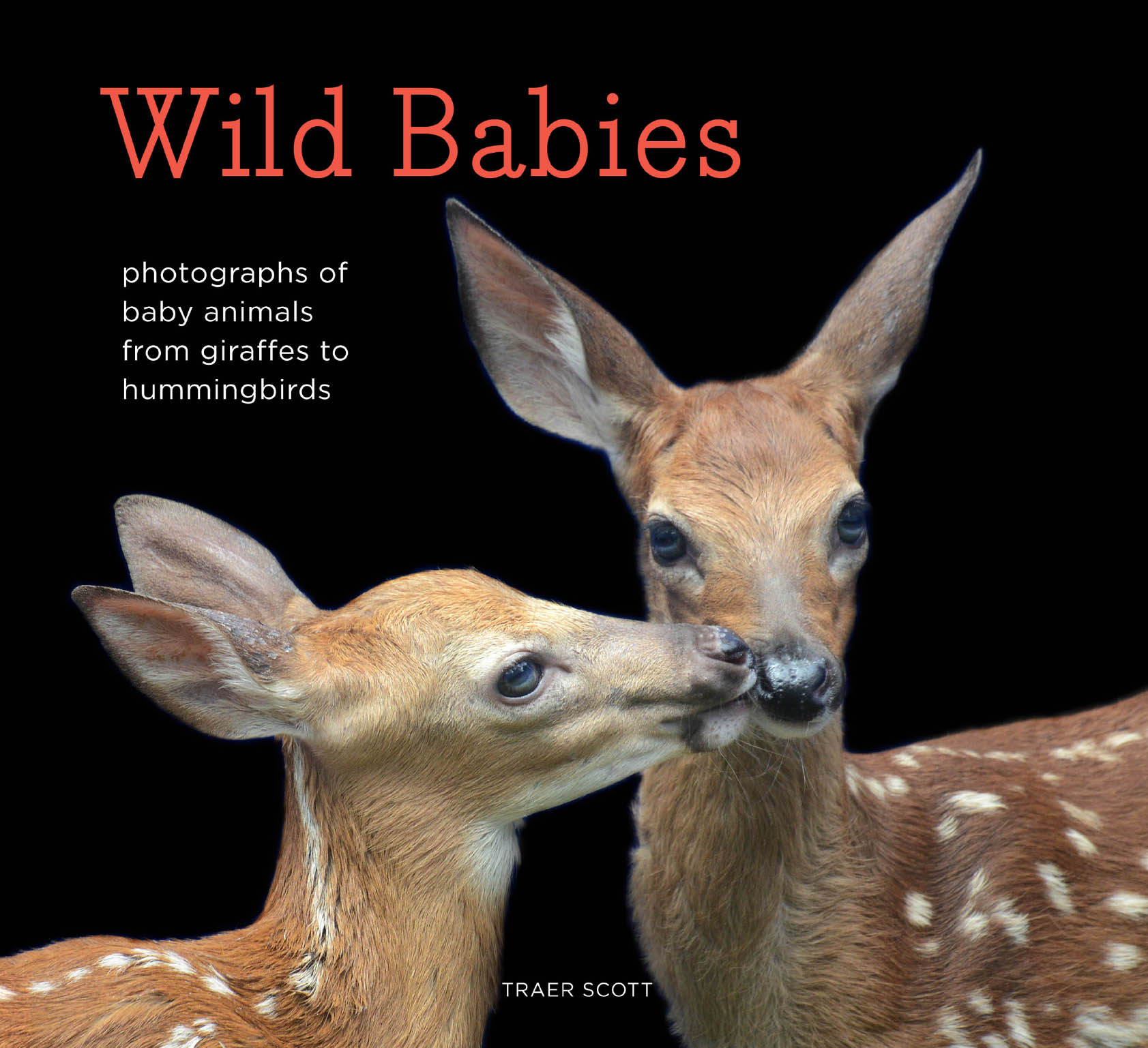

Names: Scott, Traer. Title: Wild babies : photographs of baby animals from giraffes to hummingbirds / by Traer Scott.

Description: San Francisco, CA : Chronicle Books LLC, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015040119 | ISBN 9781452134864 (hc)

Subjects: LCSH: Wildlife photography. | AnimalsInfancyPictorial works.

Classification: LCC TR729.W54 S45 2016 | DDC 779/.32dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040119

Design by Tonje Vetleseter and John Parise

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

A FRAGILE TIME OF LIFE

The animals in this book are cute. Theres no denying it. Perhaps youve never thought of a baby opossum or infant weasel as being adorable, but as you turn the pages of this book, you most likely will. Why do we find baby animals of other species so compelling? Why do these images of wild babies make us feel warm and nurturing?

The answer is that we just cant help it. As humans, we are biologically programmed to feel a need to care for our helpless offspring, which necessarily translates to us finding human infants appealing. Studies show that people feel a range of positive emotions when exposed to photos of human babies. They feel gentler and less angry, and are often flooded with a sudden need to protect and nurture the baby they see. This biological instinct is why we are able to withstand the mental and physical marathon of parenthood, but studies also show that we have the same reaction to baby animals of other species, particularly mammals.

Most baby mammals share many of the same physical characteristics of human babies: large eyes, round faces, small noses, recessed chins, and plump little bodies. Some animals, like elephants and baby chicks that do not conform to the physical type, still trigger our nurture impulse through their baby-like behaviors: lack of balance, clumsiness, and a physical closeness to Mom. However, the same mouse or opossum or raccoon that we find utterly irresistible in infancy may suddenly seem unappealing or even threatening when the baby-like features give way to adult characteristics and behavior. We may find ourselves afraid of them, repulsed by them, or even feeling aggressive towards them.

I was first introduced to the world of wild animal babies during a friends late summer wedding. It was the first outing I had been able to manage since having my daughter. We dressed our little infant in her first fancy frock, and spent the evening fretting about her being too cold or too hungry or too tired. A few minutes after the reception began, we decided it was time to leave, and began trudging to our car. Suddenly a friends young daughter came running toward us, yelling that she had found a baby squirrel. The little squirrel already had fur and was breathing, but it wasnt moving and did not respond to gentle prodding. It had clearly fallen from a very high nest, though there were no visible injuries. Often, mother squirrels will come and retrieve fallen babies within an hour or so, but the little body was ice cold; she had clearly been exposed to the evening air for some time. It seemed apparent that no aid was coming.

Momentarily forgetting that I had a newborn child who needed feeding every three hours, I instinctually took on the role of rescuer, and told the pair that I would take the squirrel home and nurse it. But by the time we drove the short distance to our house, I realized that I had made a horrible mistake. Baby squirrels need constant care and bottle feeding every two hours, not unlike my daughter. We were already struggling to find balance amidst the immense shift of becoming parents, and could not add another highly dependent creature to the mix.

In doing frantic Internet searches, I found a list of local rehabilitators listed by city and which animals they were licensed to care for. I called the nearest rehabilitator and was delighted that she not only answered the phone at 9 p.m. on a Saturday, but was willing to take in our little squirrel that very night.

I had put a heating pad under the squirrels box, as it was a chilly night and we suspected that she had been out of the nest for several hours. Her body was warmer to the touch now. Her heart beat faintly, and small breaths caused her tiny body to rise and fall ever so slightly, but she was still not moving.

Leaving my husband to put our daughter to bed, I packed the squirrel up in the car and began to drive to the suburb where the rehabilitator lived. When I arrived at the small house, I opened the box for one last look at the little squirrel. As I carefully slid the cardboard back, a furry grey head suddenly popped up through the opening, looking overly alert and a bit harried. When I handed the box to the rehabilitator, she picked the little squirrel up and determined that she was female. She said that this squirrel would join the nursery, apparently comprised of almost a dozen young squirrels of varying ages. After several weeks, she would be released at the base of a big oak to start her life as a neighborhood squirrel.

That Saturday night, a wildlife rehabilitator saved a little life that would have otherwise been lost. I was so impressed with her knowledge and dedication that I began to seek out more information about wildlife rehabilitation and the individuals from all professions and walks of life who dedicate their spare time to helping injured and orphaned wildlife. In my time making this book, I have met lawyers, students, stay-at-home moms, teachers, and construction workers all of whom give a piece of their home and a lot of their time to helping wildlife get back on their feet.

Rehabilitators are more than just caring people; usually they have to be licensed in the state where they live. It is crucial that people who are not licensed do not try to care for injured wildlife. Doing so very often results in death for the animal, and can pose many dangers and health threats to the person and their family. A licensed wildlife rehabilitator will know exactly how to care for a particular species. They will have access to the necessary medication, food, and knowledge to give the baby or adult animal the best chance for survival. They will also be prepared to dedicate the immense amount of time that it often takes to successfully raise a wild baby.

But why does nature need help? Everyone has heard the phrase, let nature takes its course, an adage that translates to us leaving nature alone to do its thing. The problem is that we are often the problem; humans are sometimes responsible for altering the natural course of things and impeding nature from taking its natural course. Every day, in every corner of our country, indigenous wild animals are imperiled as a result of humans or human encroachment. Some animals are forced out of their habitats by construction projects, many are hit by cars, babies are often orphaned when their mother is hunted or accidentally killed. In these instances, it could be said that we owe it to nature to help clean up the mess.

Next page