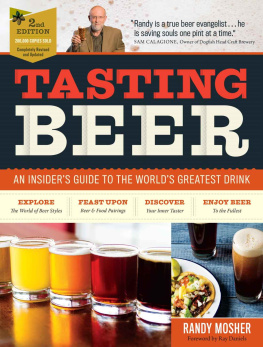

There are two kinds of beer drinkers in the worldthose who believe they know everything they need to know about beer, and those who believe theyll never know enough. The former groupby far the largestusually wants their beer, like their favorite barstool, to be comfortingly the same every time: fizzy, yellow, and ice cold. The second, rapidly growing group seeks to experience the vast diversity beer has to offer. Some may have just started venturing into the broader world of weizens, lambics, and stouts, while others may have been brewing for decades. But with every new release, every revival of a lost style, every use of a new and unexpected ingredient, theres more to learn.

If you are in that second group, this guide will help you on your explorations. It describes the basic composition and central flavor elements of beer, the different styles, and the methods you need to analyze and discuss good beer. Once you understand why some beers are tart and others spicy, why some taste like lemons and others like bananas, and why some are still and others as lively as champagne, youll soon be evaluating every pint like a professional brewer. You may never learn everything there is to know about beer, but youll have a fantastic time trying.

Cheers!

Despite all the types and stylesale, lager, bock, barleywine, and so onbeer is a simple beverage: fermented grain, usually spiced. The earliest brewers discovered the basic recipe by chance, when some sprouted grain was left alone in water and fermented, producing beer. Over time, people learned how to control the malting process, figured out that adding spices helped balance the sweetness of the grains (usually barley, but sometimes wheat or other grains), and ultimately (millennia later) realized that yeast was the magic ingredient that made the whole thing go. Despite all the categories and styles to distinguish the recipes that make up all the different beers, these are nothing more than variations on a theme first developed over six thousand years ago.

How Beer Is Made

Raw grain is indigestible to yeasts, so before it even arrives at a brewery, the grain must be converted to malta process of germination and drying that converts the starches within each seed to sugar. The first step in the brewing process is to steep this malt in hot water, making barley tea, also known as the mash. As it steeps, the malt releases its sugars into the water. A brewer may use as few as one kind of malt or as many as a half dozen; the malts add the colors and flavors needed to create each style of beer. The more malt thats used, the higher the potential strength, or alcohol content, of the beer.

Next, the brewer separates the water and spent grains and brings the liquid, now called wort (rhymes with flirt), to a boil. At this point, hops are added to balance the malt sugars with bitterness. The longer hops are in the boil, the more their acids are converted to bittering compounds; later hop additions contribute flavor and aroma. The most delicate, evanescent, aromatic compounds of hops essential oils are so volatile that the last addition may spend almost no time in the boiling wort.

Finally, the liquid is strained again and cooled. When it reaches an optimal temperature for the intended style, brewers add (or pitch) yeast and let the billions of little fungi take over. Humans, it is said, make wort; yeast makes beer. Some yeasts ferment at between 60 and 75F; these are the ales. Lager strains like it a bit cooler, just above 50F. Fermentation takes several days, and then beer is further aged (or conditioned) to let flavors round out and develop. Ales can be ready to package in a couple of weeks. Lagers, noted for their clean, elegant flavors, do better when left to age for a month or two. A small number of beers require even longer agingmonths or years, usually in wooden casks or vats. Usually very strong or made with wild, sour yeasts, these beers require the extra time to reach full maturation.

A simple glass of beer offers dozens of sensationscolors, aromas, textures, and flavors. All these can be distinguished even by the novice drinker; in some cases, beginners bring an acuity with the excitement of discovery that old pros have long lost. Yet many of the sensations are telltale clues about the ingredients and methods that went into making the beer. Developing a sense for those clues is useful in taming the chaos contained in a single pint.

The Basics

Before we get into the compounds that create certain flavors and aromas, lets go over the basics. Following are important terms used to describe general aspects of every beer.

Alcohol. Alcohol is sensed more than tasted. It may be a volatile, sharp note in the aroma or a warming sensation on the tongueor even undetectable in low-alcohol beers. Alcohol is also lethal to foam, so if your head dissipates quickly, the beer may be boozy. Beers above 6% will exhibit an alcohol note, one that usually becomes prominent by 8 to 9%.

Attenuation. Some yeasts are finicky, and some are voracious; as a consequence, they consume different proportions of malt sugars. How well the yeast has fermented the sugars is known as attenuation. A highly attenuated beer will be thinner and have less malt flavor than a poorly attenuated one.

Balance. The balance of a beer refers to the harmony between contrasting elementsusually hops and malt.

Bitterness. While dark-roasted malt imparts a coffeelike bitterness, the term bitterness generally refers to that which comes from hopsa more tangy, resinous quality. Sometimes breweries include a rating of the International Bitterness Units (IBU) for their beers; above fifty is notably bitter, and below twenty is mild.

Color. In order to get a good sense of the color of the beer, dont rely on what your glass reveals. Hold the glass up to the light and tilt it to create a shallow edgebeer will appear different in different circumstances. All of a beers color comes from malt, so while you may not be able to guess the entire grain bill, you can make inferences. Also, look to see if the color is opaque or clear, which gives clues to the degree of filtration and the presence of wheat and whole hops.

Hops. The character contributed by hops can vary broadly. In a standard tin-can beer, they fall below the threshold of human perception. In some beers, they are so abundant they exceed human perception. Beyond bitterness, they can add flavors like grapefruit, black pepper, or pine, or scent a beer with lavender, sage, or cedarjust to name a few.

Malt. Malt is responsible for the color of a beer, but it also adds flavor and some aroma. Like coffee, malt is roasted to different colors; the palest malts barely stain a beer, leaving it straw colored. Munich malts redden a beer, and dark malts blacken it. Malt also contributes flavors like bread, caramel, roastiness, nuts, leather, chocolate, and dark fruit.

Mouthfeel. One aspect of mouthfeel is body, but the term is broader. Qualities like creamy, flat or effervescent, hearty or thin are all aspects of mouthfeel.

Session. Both an activity and a beer category. Session beers are lower in alcohol to facilitate longer sessions of drinking without getting drunk.

Drilling Down

If you ever have the chance to drink beer with a brewer, listen to what he or she says. Brewers wont talk in generalities; theyll say things like Is that iso Im picking up? or I can smell the Simcoe hops. It has the appearance of a magic trickuntil you learn to recognize the signs yourself. Following are a few of the important flavor and aroma notes youll encounter and what causes them.

Next page