This book made available by the Internet Archive.

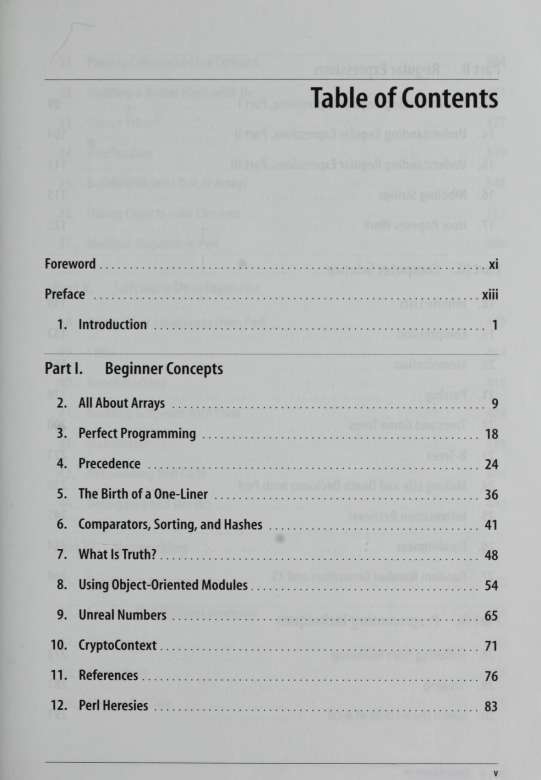

Part II. Regular Expressions

13. Understanding Regular Expressions, Part I 89

14. Understanding Regular Expressions, Part II 104

15. Understanding Regular Expressions, Part III Ill

16. Nibbling Strings 115

17. How Regexes Work 122

Part III. Computer Science

18. Infinite Lists 139

19. Compression 152

20. Memoization 161

21. Parsing 176

22. Trees and Game Trees 200

23. B-Trees 221

24. Making Life and Death Decisions with Perl 238

25. Information Retrieval 245

26. Randomness 254

27. Random Number Generators and XS 260

Part IV. Programming Techniques

28. Suffering from Buffering 273

29. Scoping 281

30. Seven Useful Uses of local 291

32. Building a Better Hash with tie 311

33. Source Filters 327

34. Overloading 339

35. Building Objects Out of Arrays 348

36. Hiding Objects with Closures 355

37. Multiple Dispatch in Perl 366

Part V. Software Development

38. Using Other Languages from Perl 389

39. SWIG 404

40. Benchmarking 418

41. Building Software with Cons 424

42. MakeMaker 435

43. Autoloading Perl Code 443

44. Debugging and Devel:: 448

Part VI. Networking

45. Email with Attachments 455

46. Sending Mail Without sendmail 464

47. Filtering Mail 472

48. Net::Telnet 480

49. Microsoft Office 485

Table of Contents vii

51. Managing Streaming Audio 507

52. A 74-Line IP Telephone 518

53. Controlling Modems 531

54. Using Usenet from Perl 541

55. Transferring Files with FTP 547

56. Spidering an FTP Site 557

57. DNS Updates with Perl 570

Part VII. Databases

58. DBI 579

59. Using DBI with Microsoft Access 587

60. DBI Caveats 595

61. Beyond Hardcoded Database Applications with DBIx::Recordset 601

62. Win32::0DBC 608

63. Net::LDAP 622

64. Web Databases the Genome Project Way 637

65. Spreadsheet::WriteExcel 656

Part VIM. Internals

66. How to Improve Perl 671

67. Components of the Perl Distribution 676

68. Basic Perl Anatomy 679

69. Lexical Analysis 685

viii Table of Contents

71. Microperl 705

Index 711

About the Authors 731

Table of Contents ix

Foreword

Mark Jason Dominus

It's flattering that Jon Orwant invited me to write the foreword for this book. After all, the title is "Computer Science and Perl Programming," and that pretty much covers it all: "Programming" is anything with any practical relevance, and "Computer Science" neatly includes everything else. You folks haven't seen the Table of Contents for the second and third Best of TPJ books yet, but I have. Take my word for it, they're concerned with "Computer Science and Programming" also.

Why did I get this job? Partly because I've written more articles for TPJ than anyone else, unless you count Chris Nandor's "Perl News" columns. But I think it's also because I got a reputation for writing articles about "Computer Science and Programming," at least as much as anyone except perhaps Damian Conway. And Damian's too busy to write forewords, whereas I'm unemployed.

Perhaps I should say something about what you'll find in this book. The theory is that the casual browser standing in the bookstore might flip to the foreword to find out what the book is about. It's a rotten theory, because hardly anyone reads the foreword even after they've bought the book. More likely, you are a reviewer, hoping for some guidance about what to say in the review. Hello, reviewer! I am happy to assist.

This book is indeed the "Best of the Perl Journal," biased though my opinion might be by the inclusion of ten of my own articles. It does not suffer from the usual flaw of the anthology, which is that the best you can hope for is that more than half of the articles are above average. On the contrary, it is by turns brilliant, witty, and profound. (Please be sure to say so in the review, and be sure that nothing could ever induce me to exaggerate the merits of this volume. No, not even the hope of an increased royalty.)

The book begins, aptly enough, with a selection of articles for beginners. (Jon used to complain that not enough people wanted to write these: "All the clueful writers want to write about stuff that displays their cluefulness," he once told me.) The following section is about regexes, and the notable feature is the series of articles by Jeffrey Friedl on understanding regular expressions. These came along very early in the magazine's history, and were a major contributor to its success, since they were important articles by a Famous Person.

The third section is the "Computer Science" section. Most of the articles in that section turn out to be more practical than you would thinkPerl programmers have a wonderful way of making everything useful and of cannibalizing the most abstruse theory. I suppose cannibalization becomes a habit after a while.

Section 4 is titled "Perl Programming Techniques," a mixed bag of subsystems (source filters and operator overloading), alternative approaches to OOP (using arrays or closures instead of hashes), and miscellany (my attempt to summarize Perl's grotesque namespace semantics, which migrated here from the "Beginners" section, and the article I wrote as a followup when the tech editors complained about my advice in the first article.) Section 5 is another mixed bag, this one loosely about tools that support development: benchmarking and configuration utilities, for example.

Sections 6, 7, and 8, on networking, databases and internals, respectively, are more homogeneous. Note that the "Networking" section covers almost every important network application except the Web; those articles will be in the second Best of the Perl Journal book, title Web, Graphics & Perl/Tk. The section on databases includes an early article on Perl's ubiquitous DBI. The "Internals" section collects the excellent Guts series by Chip Salzenberg.

All together, there are 71 of the best articles I can remember from the magazine. The only important omission is that there's no article by Larry Wall; for that you'll have to wait until the third book.

Now a personal note: In revising my articles for this book, I built a little tool to compute the word-by-word differences between my own master copies and the versions Jon Orwant provided that were to go into the book. I didn't expect many changes, because Jon had told me in the past that my articles required very little editing. I always believed that my articles went into the magazine almost exactly as I had written them. But when I saw the results of the automatic comparison, I was rather dismayed. I understood at last how often Jon had tightened my phrasing, cleaned up my rhetoric, and eradicated my verbal tics. (The original draft of this foreword began with the words "It's pretty- flattering;" if it begins with anything else now, you will know that Jon has picked up after me again.) Not only did he do this with such a light touch that I was unaware of it until now, but he was willing to spare my vanity and let me take the credit for his work. So there you have it: Jon Orwant is not only a fine writer and an acute editor, but also a kind, kind man. He is the author of only one of the articles here, but it's nevertheless his book more than anyone else's.