STEWART BRAND

SpacewarFanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums 1972

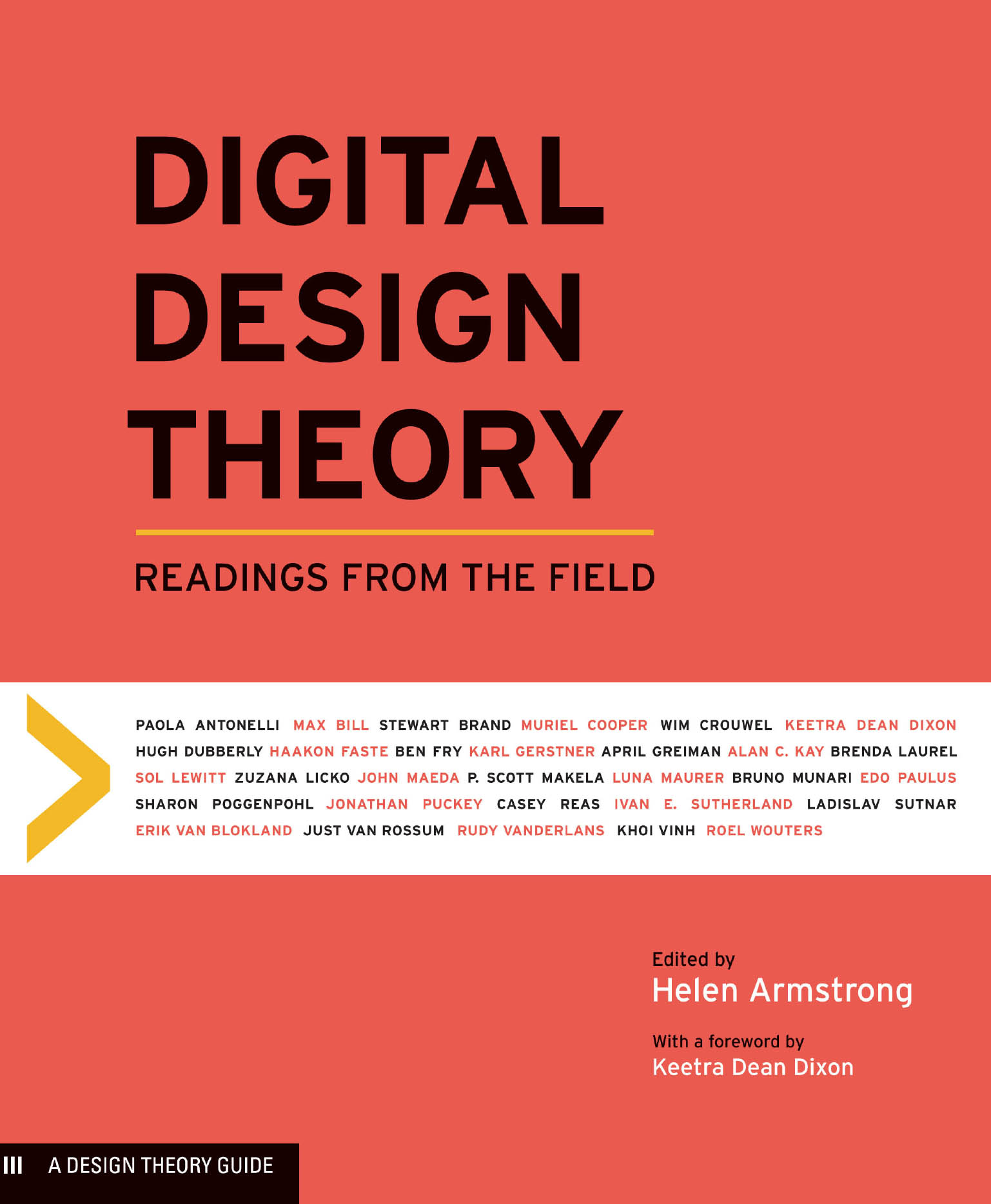

CONTENTS

| Keetra Dean Dixon

| Ladislav Sutnar | 1961

| Bruno Munari | 1964

| Karl Gerstner | 1964

| Ivan E. Sutherland | 1965

| Max Bill | 1965

| Stewart Brand | 1968

| Wim Crouwel | 1970

| Sol LeWitt | 1971

| Sharon Poggenpohl | 1983

| April Greiman | 1986

| Muriel Cooper | 1989

| Zuzana Licko and Rudy VanderLans | 1989

| Alan Kay | 1989

| Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum | 1990

| P. Scott Makela | 1993

| John Maeda | 1999

| Ben Fry and Casey Reas | 2007

| Paola Antonelli | 2008

| Hugh Dubberly | 2008

| Luna Maurer, Edo Paulus, Jonathan Puckey, Roel Wouters | 2008

| Brenda Laurel | 2009

| Khoi Vinh | 2011

| Keetra Dean Dixon | 2013

| Haakon Faste | 2015

BUILDING TOWARDS A POINT OF ALWAYS BUILDING: A Visual Foreword by Keetra Dean Dixon

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Essential to this project, of course, are the many eminent designers who graciously contributed their work. Special recognition goes to Lenka Kodtkov, Radoslav L. Sutnar, Alberto Munari, Wim Crouwel, Jakob Bill, Laura Hunt, and Nicholas Negroponte for their help negotiating the maze of copyright permissions inherent to a project such as this. I would also like to express deep gratitude to Dr. Glenn Platt and Dr. Bo Brinkman for their continuing insights and to Peg Faimon, a wonderful designer, friend, and mentor. Without Pegs support, this book would not have been possible.

A special thanks to my studentsAli Place, Danny Capaccio, Ringo Jones, Kansu zden, and Paulina Zengwho provided a strong sounding board for this collection in the classroom, never failing to inspire through their own energy and creativity. At Princeton Architectural Press, my gratitude goes to my editor, Nicola Brower, for her thoughtful comments. Finally, thanks go to my husband, Sean Krause, for his patience, love, and editing skills, and to my daughters, Vivian and Tess, who remind me each day what this crazy life is really about.

INTRODUCTION

GIVING FORM TO THE FUTURE

Designers work at the crux of accelerating technological change. We spend so much time straining to keep up that we rarely have a moment to reflect upon how we got to where we are. How did we get here? How has computation brought us to this point? This collection attempts to answer these questions. Our story begins in the late mid-twentieth century: the 1960s.

In 1963 computer scientist Ivan Sutherland wrote a computer program called Sketchpad (also known as Robot Draftsman), through which he introduced both the graphical user interface ( GUI ) and object-oriented programming, proving that not only scientists but also engineers and artists could communicate with a computer and use it as a platform for thinking and making. In the same year computer scientist J. C. R. Licklider, director of Behavioral Sciences Command and Control Research at the Defense Departments Advanced Research Projects Agency ( ARPA ), began discussing the intergalactic computer network, an idea that fueled ARPA research and developed into the ARPANET , an early version of the Internet. Soon thereafter, in 1964, IBM released a new mainframe computer family, called System/360, a family of computers capable of meeting both commercial and scientific needs. It was the first general-use computer system. Four years later engineer and inventor Douglas Engelbart, assisted by Stewart Brand, conducted the so-called Mother of All Demos, in which he presented the oN-Line System, a computer hardware and software system that included early versions of such fundamental computing elements as windows, hypertext, the computer mouse, word processing, video conferencing, and a collaborative real-time editor. Although mainframe computers were still inaccessible to most artists and designers in the 1960s and 70s, the idea of computation began to inspire visual experiments. The zeitgeist of the computer was in the air.

Two key inventions for designersand indeed for everyonehappened in the incredibly fertile period that followed: the development of the Macintosh in 1984, the first personal computer sold with a GUI ; and the creation of the Internet, used by academia in the 1980s and adopted for widespread use in the 90s. As we entered a new millennium, these two inventions became the defining tools of designers practice, not just practically but also ideologically. The personal computer brought computation to the masses while the Internet networked both mind and information on a large scale. Since the 1960s these tools have spawned technology-oriented approaches that continue to shift the foundations of our practice to focus on parameters rather than solutions, an aesthetics of complexity, and a culture of hacking, sharing, and improving the status quo. Now we move toward a fresh visual language, one driven not by gears and assembly lines but by connective tissues that bind the organic and the digital together.

STRUCTURING THE DIGITAL (196080)

During the 1960s, programmers of mainframe computers had to clearly articulate and translate a series of logical steps into the unequivocal language of the computer. They fed these steps, the program, into the machine using a punch card or punched tape. Artists and designers of the same period began to experiment with this idea by breaking down the creative process into set parameters and then structuring those parameters into a series of steps to be followed by either a human being ortheoretically at the timea computer.

Manipulating a limited number of aesthetic parameters to enact a design project was not a new idea. Earlier in the twentieth century, avant-garde artists at the Bauhausand advocates of the New Typography movement that followeddeveloped the modular grid. Widespread codification and commercial application of this concept took off after World War II as designers including Josef Mller-Brockmann, Emil Ruder, Max Bill, and later Ladislav Sutnar and Karl Gerstner began to grapple with the onslaught of information thrust at them by mid-twentieth-century society. These Swiss style designers organized information into graphic icons, diagrams, tabbed systems, and grids that could be quickly comprehended by a busy twentieth-century citizen. The postWorld War II industrial boom demanded that they develop such efficient systems for organizing and communicating information.

Grids, in particular, supported efficiency. Along with corresponding style guides, they allowed the designer to create new layouts by selecting from a limited number of choices rather than starting from scratch each time. This constraint sped up the process, encouraging designers to translate intuitive decisions into specific parameters such as size, weight, proximity, and tension. The result was a series of visually unified designs that could accommodate a wide variety of data.