Cracking the Code!

Can flashing lights send out a secret code? Did a famous spy use sketches of butterflies to hide messages? Can a digital photo hide a secret code? For centuries, spies have used many different ways to pass secret information. Codes and ciphers keep information safe from the enemy. Author Susan K. Mitchell uncovers the secrets to the amazing world of spy codes and ciphers.

"This series of books should serve as a starting point for children interested in understanding Intelligence work and may even inspire some to pursue careers in the field."

A case officer with the CIA

"A very interesting and captivating read. This series provides a good overview of the many aspects of espionage, spanning from its early history up to the present-day."

Keith T. Schwalm, former Staff Assistant

(Special Agent), U.S. Secret Service,

Homeland Security Division

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Susan K. Mitchell is the author of many books for children. She is a teacher who lives in Texas with her wonderful family.

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

Flashes of light in the darkness. Random puffs of smoke. A series of taps on metal or a jumble of mysterious symbols. To the ordinary person, none of these would mean a thing. They might go completely unnoticed. But to a spy, these could be a very important messagea secret message about the enemy!

As long as there have been governments, militaries, and spies there has been a need to pass along secret coded messages. Codes are like a language only a few people know. Letters and symbols can be used to mean different things.

Almost anything can be used as a code. Since ancient times, humans have been thinking of new ways to send secret messages. They have been hidden in thousands of unusual places. All that really matters is that both the sender and the person receiving the code know the key to decode the message.

One of the oldest codes dates back to ancient Greek times. It uses a tool called a scytale (SKIT-talee). This was a simple, round stick. With it was a long strip of paper. Letters were written down the length of the paper. It looked like nonsense.

Alone, neither the stick nor the paper meant much. However, once the strip of paper was wrapped around the round stick, a message appeared. Both the piece of paper and the size of the stick had to be very carefully measured for the code to work.

You can make your own scytale. Take an empty paper towel roll. Wrap a half-inch strip of paper around it. Now write your message across the paper. When you unroll it, the letters will be all jumbled. Have your friends use their own empty paper towel rolls to decode your message!

Image Credit: National Security Agency

This is a cipher wheel from the eighteenth century. It is believed that Thomas Jefferson invented this device. Scrambled letters are written on twenty-six wooden wheels mounted on an iron rod. To encode a message, you would spin the wheels to get a message twenty-six letters long, one letter per wheel in a row. Then, you would look at a different line of letters to write down and send to another person. To decode the message, the person would spin his or her cipher wheel to find the same arrangement of letters. Then, he or she would look at the other rows to find a readable message.

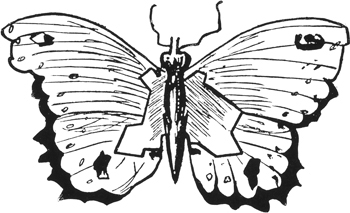

Lord Robert Baden-Powell had a talent for art. He was a harmless butterfly collector. Or was he? In reality, Lord Baden-Powell was a military spy! His most powerful weapon was his sketchbook.

Lord Baden-Powell worked as an intelligence officer in the British army in the late 1800s. On spy missions, he often disguised himself as a butterfly collector. Then he scouted out the areas near enemy forts. Armed with art supplies and a large net, no one paid him much attention. If he was questioned, Lord Baden-Powell simply asked about different butterflies in the area. The disguise always worked like a charm.

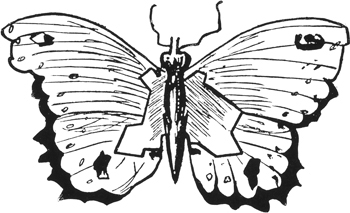

If anyone had looked closely at his drawings, however, they would have seen something far more than a butterfly or moth. Underneath the details of each drawing was a secret code. Plans for the layouts of military forts were hidden in each coded drawing. Spots on a butterflys wing were really locations of large weapons. A moth was really a complete map of a fortress and the area surrounding it.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

This is a photograph of Lord Baden-Powell. He used sketches of butterflies, moths, and leaves to send important information to British intelligence about enemy forts.

Image Credit: Andy Crawford / Dorling Kindersley

The layout of a fortress is hidden in this butterfly sketch. The jagged shape around the butterflys body shows the outline of a fortress. On the wings, marks on the lines show the locations of the guns.

Lord Baden-Powell began the Boy Scouts in Great Britain in 1907.

Lord Baden-Powell did not only use butterfly and moth drawings to hide his secret messages. The central vein on a leaf became the ground around a fortress. Small dots on the leaf showed where machine guns were positioned. Even something like a sketch of a stained glass window could hold secrets.

These sketches gave the British military detailed knowledge about the enemy during the Second Boer War in South Africa. Lord Baden-Powell was so good at acting and spying that he was never caught. His coded drawings were never captured.

The coded sketches gave British troops information that was critical in defeating enemy fortresses. Because of the drawings, they knew how to take out the enemys weapons. They knew the best place to attack. They knew the weaknesses of the fortall because of a seemingly harmless drawing!

Some codes are so complex they remain unsolved even today! Not all of them are ancient. In 1990, artist Jim Sanborn created a huge sculpture for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It sits outside the headquarters in Langley, Virginia. The sculpture is called Kryptos. On it are four coded messages. They are a seemingly random jumble of letters.

Code breakers have tried for years to figure out all four codes. The first three codes took years to crack. As of 2010, no one has solved the fourth section of the code on Kryptos.

Not all codes are written down. Imagine hiding a message in a series of clicks or flashing lights! That is exactly how Morse code works. Inventor Samuel F. Morse created the code in the early 1800s. Morse invented a machine called a telegraph. He found he could tap out a message using electricity. The electric impulses traveled by wire to another waiting telegraph machine.

A short tap is called a dot. A longer tap is called a dash. These dots and dashes are combined to represent each letter of the alphabet. They also can represent numbers and punctuation. The system is very easy to learn. It is also amazingly fast! A trained person can send or decode twenty to thirty words each minute.

![Lewin - The other Ultra : [codes, ciphers and the defeat of Japan]](/uploads/posts/book/93695/thumbs/lewin-the-other-ultra-codes-ciphers-and-the.jpg)