1. Introduction

FIGURE 1-1 Emergency Broadcast Warning

On 11 February 2013, residents of Great Falls, Montana, received the following warning on their televisions [INF13]:

The warning signal sounded authentic; it used the distinctive tone people recognize for warnings of serious emergencies such as hazardous weather or a natural disaster. And the text was displayed across a live broadcast television program. But the content of the message sounded suspicious.

What would you have done?

Only four people contacted police for assurance that the warning was indeed a hoax. As you can well imagine, however, a different message could have caused thousands of people to jam the highways trying to escape. (On 30 October 1938, Orson Welles performed a radio broadcast adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel War of the Worlds that did cause a minor panic. Some listeners believed that Martians had landed and were wreaking havoc in New Jersey. And as these people rushed to tell others, the panic quickly spread.)

The perpetrator of the 2013 hoax was never caught, nor has it become clear exactly how it was done. Likely someone was able to access the system that feeds emergency broadcasts to local radio and television stations. In other words, a hacker probably broke into a computer system.

On 28 February 2017, hackers accessed the emergency equipment of WZZY in Winchester, Indiana, and played the same zombies and dead bodies message from the 11 February 2013 incident. Three years later, four fictitious alerts were broadcast via cable to residents of Port Townsend, Washington, between 20 February and 2 March 2020.

In August 2022 the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which administers the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS), warned states and localities to ensure the security of devices connected to the system, in advance of a presentation at the DEF CON hacking conference that month. Later that month at DEF CON, participant Ken Pyle presented the results of his investigation of emergency alert system devices since 2019. Although he reported the vulnerabilities he found at the time to DHS, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the manufacturer, he claimed the vulnerabilities had not been addressed, years later. Equipment manufacturer Digital Alert Systems in August 2022 issued an alert to its customers reminding them to apply the patches it released in 2019. Pyle noted that these patches do not fully address the vulnerabilities because some customers use early product models that do not support the patches [KRE22].

Today, many of our emergency systems involve computers in some way. Indeed, you encounter computers daily in countless situations, often in cases in which you are scarcely aware a computer is involved, like delivering drinking water from the reservoir to your home. Computers also move money, control airplanes, monitor health, lock doors, play music, heat buildings, regulate heartbeats, deploy airbags, tally votes, direct communications, regulate traffic, and do hundreds of other things that affect lives, health, finances, and well-being. Most of the time these computer-based systems work just as they should. But occasionally they do something horribly wrong because of either a benign failure or a malicious attack.

This book explores the security of computers, their data, and the devices and objects to which they relate. Our goal is to help you understand not only the role computers play but also the risks we take in using them. In this book you will learn about some of the ways computers can failor be made to failand how to protect against (or at least mitigate the effects of) those failures. We begin that exploration the way any good reporter investigates a story: by answering basic questions of what, who, why, and how.

1.1 What Is Computer Security?

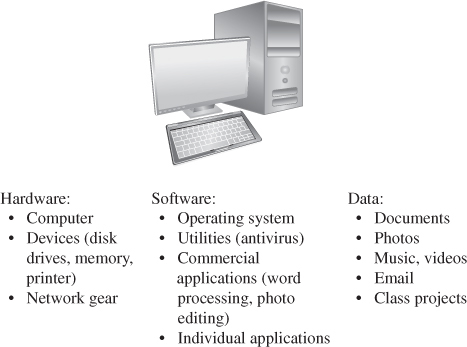

Computer security is the protection of items you value, called the assets of a computer or computer system. There are many types of assets, involving hardware, software, data, people, processes, or combinations of these. To determine what to protect, we must first identify what has value and to whom.

A computer device (including hardware and associated components) is certainly an asset. Because most computer hardware is pretty useless without programs, software is also an asset. Software includes the operating system, utilities, and device handlers; applications such as word processors, media players, or email handlers; and even programs that you have written yourself.

Much hardware and software is off the shelf, meaning that it is commercially available (not custom-made for your purpose) and can be easily replaced. The thing that usually makes your computer unique and important to you is its content: photos, tunes, papers, email messages, projects, calendar information, ebooks (with your annotations), contact information, code you created, and the like. Thus, data items on a computer are assets too. Unlike most hardware and software, data can be hardif not impossibleto recreate or replace. These assets are all shown in .

FIGURE 1-2 Computer Objects of Value

Computer systemshardware, software and datahave value and deserve security protection.

These three thingshardware, software, and datacontain or express your intellectual property: things like the design for your next new product, the photos from your recent vacation, the chapters of your new book, or the genome sequence resulting from your recent research. All these things represent a significant endeavor or result, and they have value that differs from one person or organization to another. It is that value that makes them assets worthy of protection. Other aspects of a computer-based system can be considered assets too. Access to data, quality of service, processes, human users, and network connectivity deserve protection too; they are affected or enabled by the hardware, software, and data. So in most cases, protecting hardware, software, and data (including its transmission) safeguards these other assets as well.