Introduction

I found my first proper computing job in the classified section of our local newspaper. At the time I was living with my mother in the small New Zealand town of Featherston, and the year was 1987. Just like many kids my age, I had been bitten by the computing bug and would have swept floors at night to work withor even just to be nearcomputers.

At the interview, my great enthusiasm for computing was enough to impress Neville, the operations manager. My dream came true and soon I was working the evening shift, changing tapes, loading the printer, and yes, I swept the floor at night. Later I learned that, among other things, Neville had been impressed that I had turned up wearing a smart new jumper (sweater).

How times have changed.

Interviewees today, even those with smart jumpers, might face a whole series of tough technical interviews spread over several days. They might be quizzed on their knowledge of language quirks. They could be asked to write a complete and syntactically correct implementation of a linked list while standing at a whiteboard. Their knowledge of mathematics might be probed. And then, after running this gauntlet, they might be rejected because one interviewer out of ten gave the thumbs down.

I have great sympathy for the programmer who is looking for work today. I also have a confession to make. For some years I was the stereotypical geek promoted to hiring manager; single-handedly dreaming up increasingly difficult hurdles for interviewees to jump over. I used a white board for interview exercises (though I didn't quite go so far as to insist that hand-written code should be syntactically perfect) and I made lists of technical trivia questions. Although I was never seriously tempted to pose the brain teasers made notorious by Microsoft (such as how one might move Mt. Fuji), I'm sure that in the early days of being the interviewer, I was guilty of asking a few dubious questions of my own. It is said that we learn by making mistakes, and I've certainly learned a lot over the years.

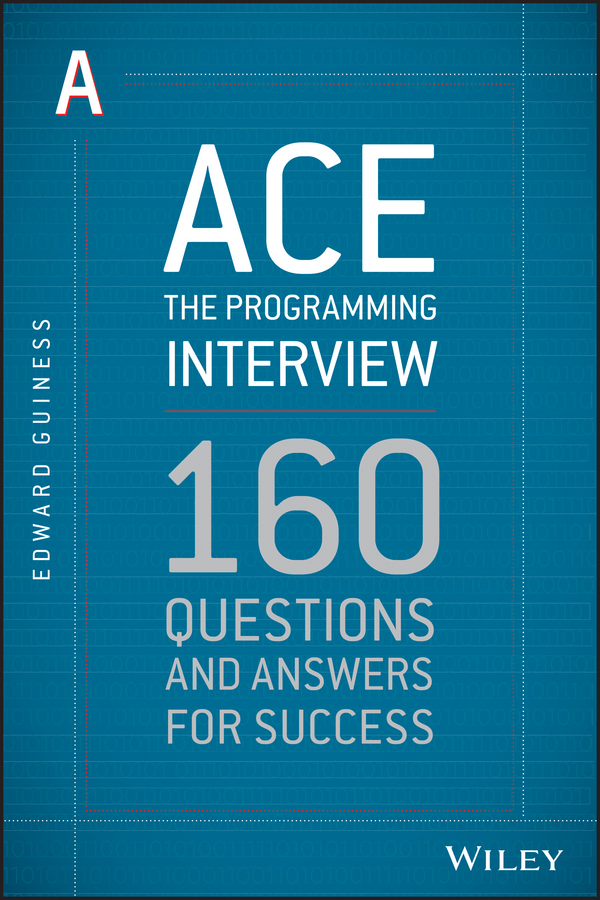

With that confession out of the wayand the disclaimer that, to this day, I'm still learning new thingslet's move on to the much more positive subject of how you, the programmer preparing for an interview, can use the content of this book to ace those tough interviews.

Code for this Book

You can find code for this book at www.wiley.com/go/acetheprogramminginterview , or you can visit: https://github.com/EdGuiness/Ace.

How This Book is Organized

This book is notionally divided into two parts. The first four chapters cover what I refer to as the soft stuffthe intangible things that you need to know and understand about how programmers are hired. Then, from Chapter 5 on, we dive deep into the actual questions you will face as an interview candidate.

Chapter 1 covers the entire process of finding a programming job, from writing your CV through to the interview. This first chapter will put the process into perspective and give you an idea of what can happen along the way. If you've ever applied for a programming job, much of this will be familiar. What might be less familiar to you, in chapter one, is the insight into how the hiring manager experiences the process and the pressures that drive companies to recruit programmers.

Chapter 2 is about phone interviews. In a number of important ways a phone interview can be more harrowing than an in-person interview. As a candidate, you will have fewer environmental clues about the company you're talking to. You can't see the dcor, how people are dressed, the atmosphere, etc. The first phone-based interview is like a cold sales calland programmers are typically not too keen on receiving let alone making these kinds of calls. The key to a confident and effective phone interview lies in preparation and being somewhat organized. It's common and natural to be apprehensive about the phone interview, but being overly nervous can get in the way of communicating effectively. We will look at strategies to calm excessive nerves, including a look at what to expect on the call. Cheat-sheets are invaluable when answering tough questions on the phone, and this chapter discusses how to prepare these cheat-sheets.

Chapter 3 covers in-person interviews. As with phone interviews the key to a successful face-to-face interview is preparation. The in-person interview is usually longer than the phone interview and will cover more aspects of your application in greater depth. We will look at how to prepare for the interview, how to ensure you communicate effectively, and we will look at what makes a good answer to a tough interview question.

Handling the job offer and negotiating a great deal is covered in Chapter 4. Despite its importance, this final stage is often overlooked by applicants and employers alike. A poorly-negotiated deal can set an undesirable tone to the employer/employee relationship and the benefit of taking time to consider the agreement before signing up cannot be over emphasized. It should not, and does not need to be difficult or drawn-out, but it does need some careful handling.

Then we will dive deep into a long list of many questions you might face at an interview. Starting from chapter five, each chapter contains a categorized set of questions you might face at the interview.

Chapter 5 covers programming fundamentals. Regardless of whether you are a recent graduate or a software development veteran, if you cannot demonstrate mastery of programming fundamentals you will struggle in most technical interviews. If you are confident and experienced then you may wish to skim-read this chapter; otherwise, you should start here to ensure you can nail the basics.

Chapter 6 covers a subject of increasing importance as employers get wise to what really matters. Here we look at the vital topic of writing good-quality code. This is a slightly elusive subject because programmers are not unanimously agreed about every aspect of what makes code good. On the other hand there are many widely accepted practices that will be in the top-ten essential lists of experienced programmers. In this chapter, along with a good list of questions and answers, you will find a condensed version of good practices that enjoy near-universal acceptance. Whatever your personal view on these so-called best practices happens to be, you ignore them at your peril. Interviewers want to know that you are at least aware of if not fully conversant with them.

In Chapter 7 I've collected a group of tough interview problems that some hiring managers will hold dear to their hearts. These are the problems that, in all likelihood, they have gathered from their own efforts as programmers, based on the hardest or most thorny problems they have faced. Multi-threading, race conditions, locks, and deadlockshere lie some of the more challenging areas for most programmers, and the questions in this chapter might challenge even the most experienced programmers. There are almost endless pitfalls and gotchas, and here we will look at some of the most common. Experienced developers must be able to demonstrate familiarity with these problems along with their solutions, and if you are less experienced you should at least be aware of them.

The subject of Chapter 8, language quirks and idioms, is somewhat controversial. It contains a list of what might be considered pop-quiz questions, the kind that are trivially answered by searching the web. The point of these questions is that most experienced programmers have explored these dark corners of their programming languages, and can therefore reasonably be expected to know of edge cases that can bite the less experienced.

Next page