CHAPTER ONE

The Squalor in the City

On every night in that cold, clear week before Christmas 1664, the thick white candles had burned late in the Palace of Whitehall. Their dim trembling glow cast gentle shadows on the tapestried walls and was reflected in the smooth silent waters of the wintry river outside.

Lord Sandwich, the Admiral commanding in Portsmouth, had reported that from the West Country a strange new star had been sighted. News of this star had also come from places as far apart as Spain and Danzig.

King Charles II, superstitious, fascinated by the occult, by signs and portents, moved by the utterances of astrologers and soothsayers, and only recently restored to his throne after the end of Cromwell's dictatorship, decided to see this for himself. A comet was not seen unless great and moving events were due; it was conceivable that these might affect him. Thus, each evening he had waited patiently in the huge ground-floor withdrawing room, hung with tapestries for warmth and effect, heated by a fire crackling in a metal grate large enough to hold logs as long as a man.

He waited in no discomfort for its appearance: his Palace had a frontage of nearly half a mile along the river bank, and was unquestionably the greatest house in his Kingdom, and also much more than a King's Palace; it was his home, his office, a meeting place for scientists and courtiers, a centre of royalty and intrigue, a city within a city. The Palace was surrounded by gardens, and it was the King's custom to walk in them every morning and check the accuracy of his watch by a sundial.

King Charles was fascinated by time and how it was measured. Beyond the great room where he awaited a sight of the new star, a small staircase led to his Closet, possibly the only room where he could be himself, without bothering with the pretence of Royalty; where his collection of clocks with moving figures, gilded pendulums, strangely wrought hands and figures chimed and ticked away the hours of waiting.

It was hot near the fire, but elsewhere in the high-ceilinged room the dark velvet curtains that hung across the doorways moved and trembled under the fingers of the wind. Beyond this withdrawing-room was the King's bedchamber, overlooking the Thames, with the fishing boats, the barges and all the traffic of the river.

The King's fiddlers and musicians played endlessly, softly, impersonal as eunuchs in the background, and then suddenly came the news they expected. The music stopped, and the King crossed to the windows of thick cloudy glass and opened them. Stars glittered like a thousand eyes above him in the freezing sky; and then across the frozen arch of heaven he saw a strange star moving.

It seemed larger and yet less bright than the others and for a comet was disappointing; it had no tail and no one could be positive where it had originated or where it went, for abruptly it melted away in the infinite darkness. King Charles was left in the suddenly silent room with the cold wind from the river blowing on his face.

In the City of London, about two miles to the east of the Palace, thousands of the King's subjects also sat up to see the passage of what they called The Comet'. They stood on higher ground than the Palace, and many swore that it almost touched the rooftops; an exaggeration, but an indication of their alarm and dread at the unknown. It had been visible on several nights, and with each sight of it the feeling grew that this must surely herald some event of immense importance to London. If not, then why had it come so close?

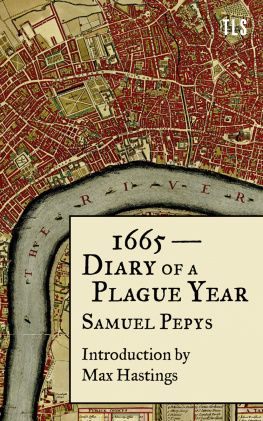

Samuel Pepys, the Secretary to the Admiralty, went out with his porter at two o'clock on the morning of Christmas Eve to see this star for himself. Lord Sandwich, who had first reported it, was a relation and had nominated him to a clerkship in the Admiralty. Pepys made it his business to see and note all occurrences of interest. The arrival of a comet naturally aroused his curiosity.

Someone told him that it could best be seen from Tower Hill. The night was bright and cold, with nearly a full moon, and the ruts in the road left by carriage wheels had frozen and glittered silver with frost as they climbed. Pepys saw the comet very clearly, noting that it passed 'so very near the houses' that many people considered 'this imported something very peculiar to the City alone'.

And what a small, strange City, lying under the hard mantle of frost, did the faint and flickering trail of that comet illuminate! The City of London stickled with short twisted chimneys, thick as the bristles on a brush, with its 109 church spires, and the houses of lath and tar and plaster; with huts and hovels where thousands crowded together for warmth and necessity, had more in common with the Middle East and the Middle Ages than any Western city since.

It was a city of unbelievable contrasts; a nobleman's house could contain sixty servants, from Steward, Gentleman Usher, Gentleman of the House, to scullions; yet there would be no proper lavatory, apart from a stinking 'house of easement'. Although Sir John Harington had invented the water-closet seventy years earlier, and Queen Elizabeth had copied his design for Richmond Palace and Queen Anne had installed a WC in Windsor Castle, most people still considered this an unnecessary affectation. Servants were so cheap - a good maid cost barely thirty shillings a year - that there was no lack of labour to clear away filth. Bathrooms were similarly rare; a man was old at forty and senile at fifty; yet if he were rich he lived on a scale virtually impossible today. Breakfast for the wealthy consisted of oysters, anchovies, tongue, wine and Northdown ale. And this was only a preparation for the main meal at noon.

Here in the large houses in Covent Garden and Whitehall they ate huge quantities of soups, roast mutton and fish served with pungent sauces; tarts, pies and cheese. Salads contained such strange and exotic ingredients as rosemary, borage flowers, even violet buds. They ate until the sweat streamed down their faces: huge steaming joints of pork, beef or venison, capon, teal, pheasant, snipe, pigeons and larks.

The poor did not fare so well: they lived on bread and roots stolen from farms, on any small animals they could snare, or what the rich men left them.

In London, then as now, rich and poor lived close together; in one street would stand a mass of garrets and filthy tenements swarming like hives with people; across the way could be the town house of a nobleman costing 50,000.

Physically, the City was tiny. It covered barely 448 acres, two-thirds the size of the present-day borough of Chelsea, one-sixth the size of London Airport, about half the total of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens put together.

Superimposed upon a modern map of Greater London, its river boundary extended for barely a mile, a curving stretch of water from the fifteenth-century Baynard's Castle at Blackfriars to the Tower.

A stout city wall, more than thirty feet high, and nearly as thick, a relic of days when armed bands would ride in from the country round about to loot and rape, ran north from Blackfriars to the first of the City gates - Ludgate, a short distance east of what is now Ludgate Circus. From there the wall enclosed the site of the present Old Bailey, and continued on to Newgate, another of the main City gates with which was combined one of London's chief prisons. On to Aldersgate, the wall turned north to Cripplegate, then east along London Wall to Moorgate and Bishopsgate. Finally, it bore south to Aldgate and the Tower.