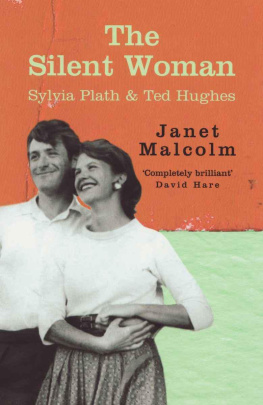

Also by Janet Malcolm

DIANA AND NIKON

PSYCHOANALYSIS: THE IMPOSSIBLE PROFESSION

IN THE FREUD ARCHIVES

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, N OVEMBER 1990

Copyright 1990 by Janet Malcolm

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in different form, in The New Yorker. This edition was originally published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., in 1990.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Malcolm, Janet.

The journalist and the murderer / Janet Malcolm.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79787-2

1. Journalistic ethicsUnited States. 2. Investigative reportingUnited States. 3. JournalismUnited StatesObjectivity. 4. JournalismSocial aspectsUnited States.

I. Title.

[PN4888.E8 1990b]

174.9097dc20 90-50156

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

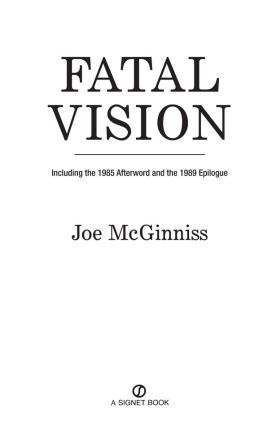

Newsday, Inc.: Excerpts from transcript of Bob Keelers interview with Joe McGinniss, The Newsday Magazine, July 1983. Copyright 1983 by Newsday, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

Princeton Alumni Weekly: Excerpts from Michael Malleys review of Fatal Vision by Joe McGinniss, Princeton Alumni Weekly, 1984. Reprinted by permission.

South Carolina Educational Television: Excerpts from transcript of filmed interview of William F. Buckley with Joe McGinniss, Firing Line, September 18, 1987. Reprinted by permission.

Sterling Lord Literistic, Inc.: Excerpts from Heroes by Joe McGinniss. Copyright 1976 by Joe McGinniss. Reprinted by permission of Sterling Lord Literistic, Inc.

v3.1

To Andulka

So a novelist is the same as a journalist, then. Is that what youre saying?

Question asked by Judge William J. Rea during the MacDonald-McGinniss trial, July 7, 1987

Contents

When I walked into Daniel Kornsteins office in mid-Manhattan, a week after the settlement, he said, Didnt you get my message? I called to cancel this appointment. I looked at him innocently. Two days earlier, he had agreed to see me, and almost immediately had repented of it, leaving a message on my answering machine cancelling the meeting. Inspired by Keelers lecture on the necessity for reporters to report, I decided to ignore the message, and turned up in Kornsteins office at the appointed hour. He wearily accepted my presence and immediately declared, McGinniss and I are not going to talk about the case or coperate on it. He was a pained-looking, short, dark-haired youngish man.

You sent me that letter, I said.

When we wrote the letter, we wanted to alert the media and make people aware of the new doctrine being advocated, Kornstein said. The case is over as far as we are concerned. Everything we want to say is in the transcript. Particularly the cross-examination of MacDonald and my summation. These were the key moments of the trial. We think the public record speaks for itself. I try my cases in the courtroom.

Then why did you send out that letter? I asked.

Kornstein gestured helplessly. Im sorry. I cant answer you. Then he said, The judge in the case didnt seewas blind tothe First Amendment implications of the case. He is a new federal judge, appointed in 1984. He had been a state judge for sixteen years. He once played professional baseballthe Chicago Cubs were interested in him.

I asked a question about the trial, and Kornstein again said, Im sorry. I cant answer you. He added, We are trying to put the case behind us.

Would you rather I didnt write about it? I asked.

I would never want to say I would rather that something were not written, Kornstein said piously.

I asked him if his offer to let me read documents in his officean offer made before McGinniss broke off relations with mestill held. Its a matter of convenience for me, I said. Your office is a few blocks from where I live, and Bostwicks office is three thousand miles away.

Kornstein said he would consider my request and let me know. Suddenly, he said, Do you know anything about me?

I looked at him with interest, and thought, Now all will be explained. This is going to be one of those moments of revelation, when the beggar discloses that he is the prince.

I am Vanessa Redgraves lawyer, Kornstein said. I represented her in her suit against the Boston Symphony.

It was time to go. Will you let me know if I can read those trial documents here? I asked. Ill give you my phone number.

No, no, I have it, Kornstein said, shuffling through papers on his desk. I have dozens of pieces of paper with your phone number on them. I know your number by heartand then, bitterly, comically, he recited it. He presented me with two books he had written (Thinking Under Fire: Great Courtroom Lawyers and Their Impact on American History and The Music of the Laws) and politely escorted me to the door. I never heard from him again.

Did you ask Bostwick if he took the case on contingency? Joseph Wambaugh said to me when I called him at his house in San Marino. You can depend on it that he did. Before I could tell him he was wrong, he went on, You can bet the bank on it. Otherwise, it wouldnt have got as far as it did. I myself have been sued so many times that it doesnt matter whether its Mr. Bostwick or somebody else; its always the same. You could confer with every attorney in town, and you could draft the most binding, airtight, rock-solid legal release in the world, and the subject would sign itand you could still find yourself in court, because any imaginative, resourceful lawyer can dream up a cause of action and bring a lawsuit. What does he have to lose? In Britain, if someone brings a libel action he runs a certain risk, because if he doesnt prevail he has to pay the defendants legal fees. Here the plaintiff risks nothing, and once the mechanism of the suit is in motion the defendant is going to sufferand I mean suffer. He immediately starts hemorrhaging his hard-earned bucks. Very few people have the stamina to endure one of these lawsuits. To defend himself, McGinniss had to come out here and live in a hotel for six weeks. He has a young child, he has a young family, he has a life as a college professor, hes trying to write a book. He gave all that up for the principle of coming out here in defense. The MacDonald side would have settled; they would have settled for the same amount early on. McGinniss refused as a matter of principle. But when he came out here and got ground up in the system and dragged through it and saw what it was really aboutits about the contingency systemhe said, Principle is principle, but this is really killing me. I saw McGinniss toward the end. He looked ten years older. I assure you, when youre the victim of one of these lawsuits you are awake at three a.m. even if you dont drink. Youre awake with the boozers, going crazy with homicidal impulses. My first nonfiction book, The Onion Field, brought me three lawsuits. One of them lasted twelve years. Think of that. Children grow up. Think of how many nights I saw at three a.m. At that time, publishers didnt have insurance policies, the way they do now. Guess who paid for that lawsuit. My publisher and I split it down the middle. These contingency lawyerstheyre like garden slugs and boll weevils. You cant get rid of them. Where is Agent Orange when we really need it? These guys are everywhere. We have twenty-five thousand lawyers in L.A. County. If we adopted the British system, all these contingency lawyers that keep spewing out of our law schools would have to go do something else theyre qualified for, like selling aluminum siding in Indiana or Veg-O-Matics on TV.

Next page