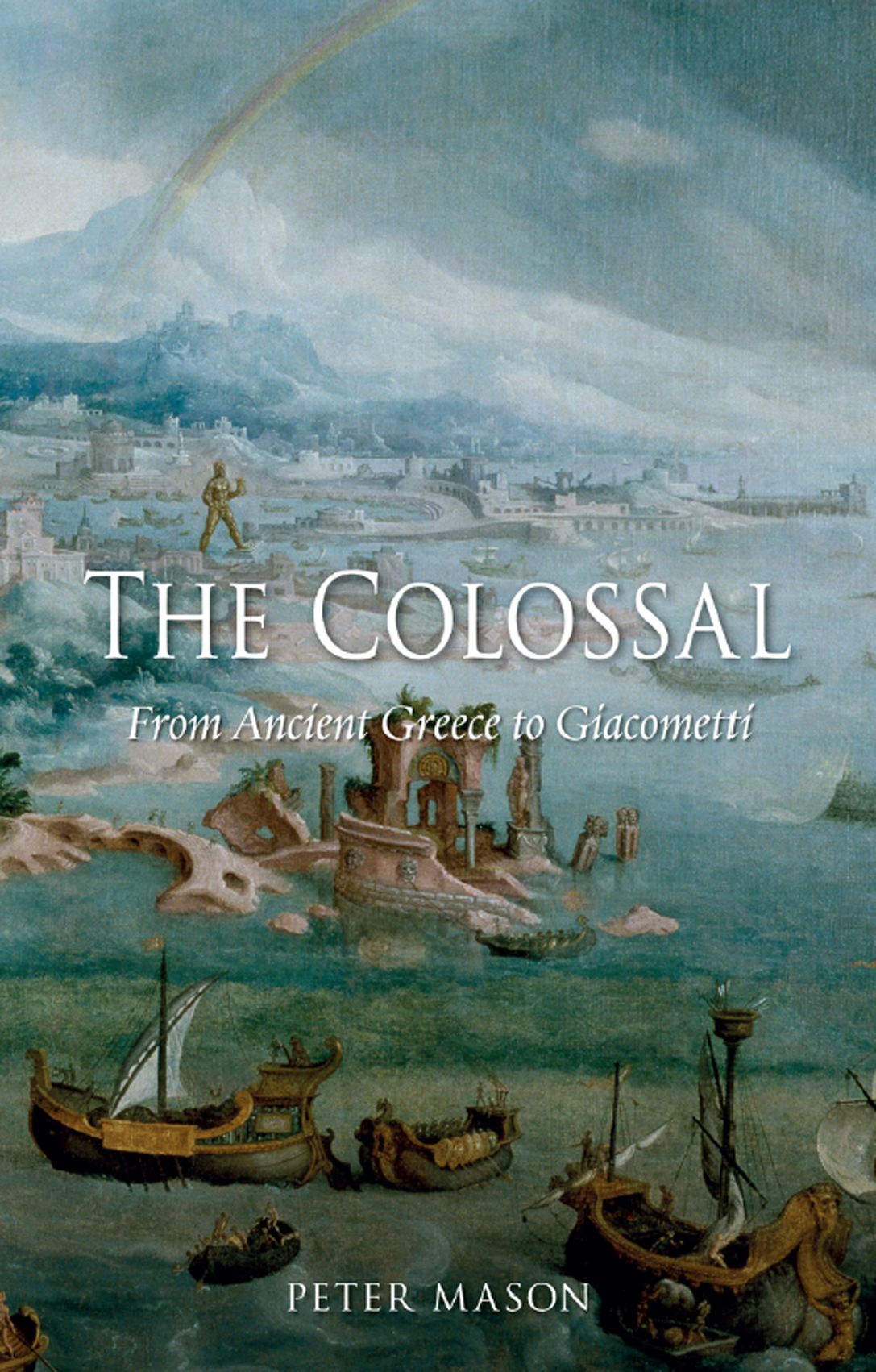

I NTRODUCTION : I NVENTIONS OF

THE C OLOSSAL

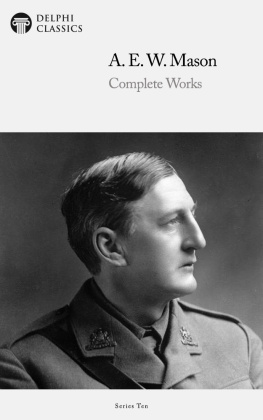

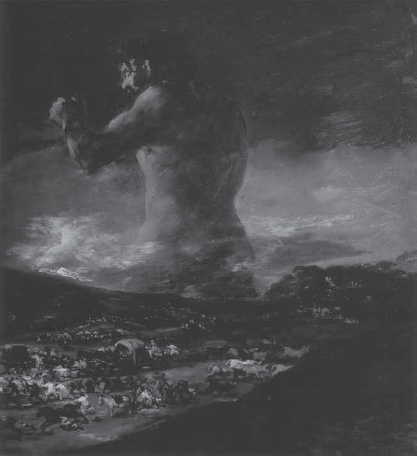

A striking absence from the exhibition Goya en tiempos de guerra held in the Museo del Prado, Madrid, in 2008 was the museums own painting variously known as The Colossus, The Giant or Panic. The question of attributions in the case of the oeuvre of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes is a vexed one, but the discovery of the initials AJ and alleged imperfections in the rendering of the animals have led some to credit the work to Goyas assistant Assensio Juli. Its title in an inventory of Goyas property, drawn up in 1812 after the death of his wife in that year, is The Giant.

This might look like no more than a quibble, for we are accustomed to use the words gigantic or colossal as virtual synonyms. For instance,

The account of the colossal offered in this book, however, sets out to show that the assumption of such an equivalence between the colossal, the gigantic or the massive has not always been the case. In fact, as regards the colossal, no guru, no method, no teacher: apparently no one has yet attempted to theorize the colossal. The present response to that lack owes some of its inspiration to the philosopher J. L. Austin. so we here initially take colossal to designate whatever is referred to as colossal in conventional usage: the Colossus of Rhodes, the Roman Colosseum, and so on. And from those footholds we attempt to construct an account of the colossal based on common usage, but with the ambition of constructing, piece by piece, a theory of the colossal that goes beyond the commonplace.

Neither a theory nor a history of the colossal as the words theory and history are usually understood, the arrangement of this text is broadly, but not strictly, chronological. Instead of attempting to narrate a linear history (which in the present case would be impossible anyway), it keys various instances of the colossal into their various specific temporal and cultural frameworks in a manner that is more archaeological than historical. Thus the obelisks that can be viewed in public places in Rome today are set within a series of archaeological strata extending backwards from the present to Papal Rome of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, further back still to imperial Rome, and even further back to ancient Egypt. The discussion of the stone statues (moai) situated on Easter Island links them to both the age of exploration and discovery of James Cook and others, and the present status of Easter Island as museum island. In a later chapter, discussion of the moai transported from the island to new settings elsewhere links them to the age of imperial expansion and rivalry as well as to present-day debates on forms of display. The colossal heads of the Olmecs similarly straddle two moments: their discovery towards the end of the nineteenth century when Freud, Darwin and others were changing the paradigms of European thought about the person, and their presentation in the era of Surrealism. The relation between technology and Surrealism that Walter Benjamin perceived structures the last chapter, which ends with the colossal Cube of Alberto Giacometti.

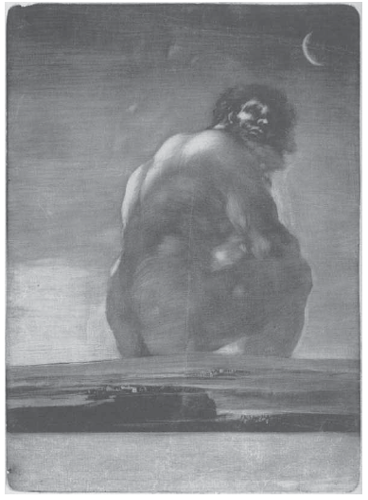

2 Francisco Goya y Lucientes, The Giant, c. 1818, aquatint and burin.

The choice of Giacometti, an artist more noted for his miniature works than for anything gigantic, is not as strange as it may seem. The word colossal, it is true, immediately conjures up those two ancient monuments, the Colossus of Rhodes and the Roman Colosseum. As they were both on a large scale, this seems to be a natural enough application of the term. But a passage from the Agamemnon by the fifth-century BC tragedian Aeschylus points in a different direction. The scene is the grieving Menelaos, whose wife Helen has deserted the palace in Argos in pursuit of her lover Paris. The chorus chants:

From desire for one beyond the sea,

A phantom will seem to rule the palace.

The phantom is the image of the absent Helen, for whom Menelaos still longs even though she has crossed the sea to Troy. In seeming to rule over the palace, the phantom thus stands in for her. The chorus continues:

The charm of the well-shaped kolossoi

Is hateful to the husband.

Whatever meaning the word kolossoi has here, it can hardly refer to anything gigantic. These are sculpted blocks that contrast with the absent bride not because of any notion of size, but because their dead material contrasts with the living body that is far away. They remind Menelaos of that very fact, instead of consoling him. The passage concludes:

In the absence of eyes,

All Aphrodite is gone.

The phrase in the absence of eyes is unclear, but whether we take it to refer to the sightlessness of the statues themselves and their inability to stimulate passion on the part of Menelaos, or to the disinterested gaze of Menelaos himself, the result is the same: like the phantom that will seem to rule the palace, the shapely statues are substitutes for the missing bride, they stand in for her, they replace her, though in a far from lifelike way.

This and other Greek evidence to be discussed in the following chapter, as well as studies of the etymology of words like kolossos, all point to the existence of an understanding of the colossal in which it is not size that is of primary importance but, as we shall see, such characteristics as immobility and sightlessness, singleness and verticality. We can go further. Though the Greek model does not necessarily imply figuration indeed, the Greek kolossos is often referred to as aniconic its very role as a substitute for a living being confers a measure of anthropomorphism on it. Thus though many of the examples considered in this book are large or even very large, it is not size that is, in the last analysis, the determinant factor.