Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the librarians, editors, curators, archologists and others who helped make this book possible. Priceless technical assistance came from Diana Abrashkin, AIA, of Boston, and archologist Marina Piranomonte of Romes Sovrintendenza alle Belle Arti. For their advice and help we are indebted to Robert Bernstein, former chairman of Random House; Professor Jane Ginsburg of Columbia University; Mario Gori-Sassoli of Romes Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica; the late Hans Heinrich Coudenhove-Kalergi of London; Cheryl Hurley of the Library of America; Inge Heckel of the New York Academy of Interior Design; and Mark Piel of the New York Society Library.

We owe a special debt to the late historian and archologist Cesare DOnofrio of Rome for sharing his profound love and scholarly knowledge of his city with us, and to the Biblioteca Hertziana for generously making available to us the wonderful photographs of Rome that Mr. DOnofrio took over the years, and which appear (many of them for the first time) throughout this book.

Finally we wish to thank friends and family who patiently listened to our endless prattle about Rome and cheered us on, among them Carlo Fruttero, the late Franco Lucentini, Baroness Olga von Kollar, John and Mary Gibbons, Prince Carlo Massimo, Robert and Dina McCabe, Paul and Chantal Cannon, David Olan, Dotty Attie, Sarah Schulte and so many others it would take another book to list them all.

We are grateful to readers who alert us of errors in the book, or provide other useful information or suggestions to help improve and update it. Write us c/o the publisher or by e-mail to We will do our best to reply to everyone.

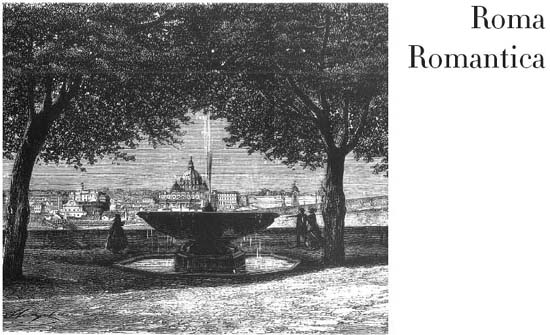

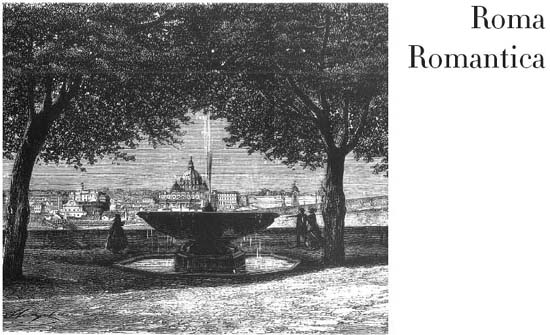

Annibale Lippis fountain and a view from the Pincian in the early 19th century

ROMA ROMANTICA

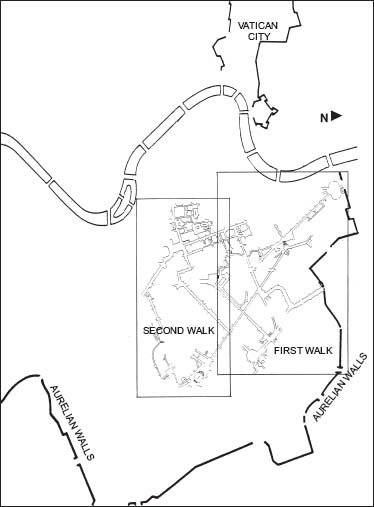

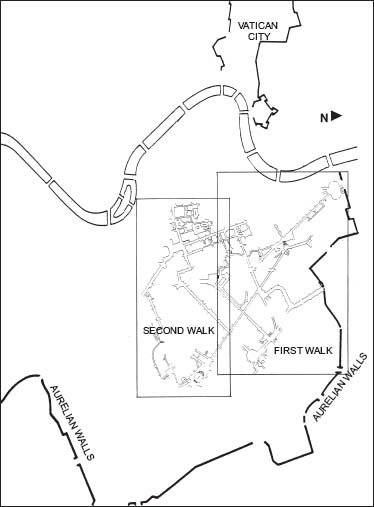

FIRST WALK

1. Porta del Popolo and the Walls 42

2. Piazza del Popolo and the Church of S. Maria del Popolo 44

3. From Piazza del Popolo to Piazza di Spagna: Via del Babuino and Via Margutta 50

4. Piazza di Spagna 54

5. Via Condotti 58

6. From Piazza di Spagna to the Trevi Fountain 62

7. The Trevi Fountain and on to the Quirinal 64

8. The Quirinal 67

9. From the Quirinal to Quattro Fontane 70

Midpoint of walk

10. The area of the Baths of Diocletian: from S. Maria della Vittoria to S. Maria degli Angeli 74

11. Piazza Barberini and Via Veneto 82

12. Via Sistina and Trinit dei Monti 87

SECOND WALK

1. The Viminal and Esquiline churches: S. Pudenziana 92

2. S. Maria Maggiore and S. Prassede 95

3. On the Esquiline Hill: S. Martino ai Monti and S. Pietro in Vincoli 104

Midpoint of walk

4. The Counter-Reformation churches: Il Ges 110

5. S. Maria sopra Minerva 115

6. S. Ignazio, the Collegio Romano and the Caravita Oratory 119

7. The Corso in modern times 123

8. From the foot of the Quirinal to S. Silvestro 128

INTRODUCTION

To lovers of Rome the term Roma Romantica indicates those areas of the city that in the late 16th century were the starting point of a slow resettlement, replacing with people and stone the vineyards and wastelands that had invaded much of the citys high ground after the fall of the Roman Empire. The new settlement was intended to spread the population more generously, after the centuries of crowding inside the Tiber bend, where the Romans had confined themselves since the fall (p. 28). Our two Walks will cover this area as well as an adjacent one sharing many of its characteristics.

It is worth stressing that Roma Romantica is merely a rough-and-ready designation that stems mainly from the fact that so many figures of the Romantic movement chose to reside in this new and fashionable area. Yet far from coinciding chronologically with Romanticism (late 18th to mid-19th century), Roma Romantica extends either side, to a total of four hundred years or so from the 17th to the 20th centuries. Moreover, those who use the term as a topographic definition tend to associate it with contemporary notions of sentimentality and romance (la dolce vita), which have little if anything to do with Romanticism as an artistic and literary movement. Yet these modern notions do contribute to the spirit of at least some of the area, and so many (ourselves included) see some value in the Roma Romantica label as a crude but practical aid to conveying general ideas about a place and time.

Among the earliest of these notions is the close historical association of the area with the Counter-Reformation (16th-17th centuries), that sharp reaction to the threat of Protestantism, and repentance for the worldliness and paganism of the Renaissance. The idealism and moral uplift of the Counter-Reformation found artistic expression in the Roman baroque, which, though present throughout the city, positively dominates the architecture in this area.

The Triton Fountain

Later, the area took on the elegance of the 18th century, though in a city steeped in religion it never acquired the frivolous tones it had elsewhere. Here, at the heart of Christianity, the experience of Rome powerfully affected two key figures in the history of Romanticism and neo-classicism: Goethe, the polymath and matchless interpreter of the Zeitgeist, whose stay in Rome had a major impact on his thought, and another German, Winckelmann, the archologist-sthete whose ideas form the basis of neoclassicism in art. Both lived in the Romantica quarter.

Rome had been an international centre of the arts since the Renaissance and a magnet for foreigners seeking artistic and spiritual fulfilment. The flow increased in the 18th century, the quintessential era of the Grand Tour, and came to a climax in the early decades of the 19th century, as the area acquired its most specifically Romantic character. These visitors came above all to see the classical ruins, and spent their time there; but most of them were lodged in the recently redeveloped quarters, where their quest for cultural self-improvement was able to encounter that peculiar blend of religiosity and voluptuousness which was, and in part still is, the Roman way.

English Grand Tourists in Rome, mid-18th century

After power shifted from the papacy to the Italian state in the late 19th century, Rome underwent a radical and unfortunate transformation intended to make it a modern capital. Many parts of Roma Romantica, however, have escaped major changes. Indeed, some of their elegance and emotional appeal spilled over into new districts nearby built in the belle poque period at the end of the century. Other areas have deteriorated badly. Ironically, the districts of Rome which are today most in need of rehabilitation are those built after Rome became the capital of Italy in 1871. In this book they will be included mainly as optional Detours, though even here the visitor will find many sights of interest and much to admire.