Sources for the study of the ancient city of Rome are varied in both medium and usefulness. Several collections have been made to aid scholars research, of which the most exhaustive is the monumental work of Giuseppe Lugli (LUGLI 195262; DUDLEY 1967; COULSTON, DODGE and SMITH forthcoming). A very useful overview is provided by Amanda Claridge (CLARIDGE 1998, 316), particularly a list of classical literary texts which touch upon the citys history and topography. This appendix takes the opportunity to expand on a number of important source areas and to provide bibliographical introduction.

REGIONARY CATALOGUES

Two surviving 4th century catalogues, entitled the Notitia ( c . AD 354) and the Curiosum ( c . AD 375), comprise lists of structures and topographic features listed first by regio (the 14 administrative sub-divisions of the city instituted by Augustus), then by type of feature.

The latter include local officials, wards, individual houses ( domus ) and apartment blocks ( insulae ), store-buildings ( horrea ), large and small baths ( thermae and balneae ), fountains and reservoirs, obelisks, bridges, hills, open spaces ( campi ), fora, basilicas, aqueducts, main roads, circuses, amphitheatres, colossal statues, honorific columns, markets, theatres, gladiatorial schools, naumachiae , large equestrian statues, nymphaea , gold and ivory gods, marble arches, gates, brothels, public lavatories, military formations and camps.

The texts are concerned to enumerate throughout, but this is not done accurately with the result that end-totals do not tally with individual listings. It is clear that accuracy was not important to the compilers and that the Catalogues were not designed to be used for the purposes of urban administration. Rather, they were a celebration of the scale and richness of the city, which may be compared with other ancient laudatory works (eg Zachariah of Mitylene, Syriac Chronicle 10.16; LUGLI 195262, I, 10912), and they were thus the precursors of medieval guide-books and mirabilia . Thus, these figures have to be very cautiously applied, for example when matters of public facilities, housing and population are discussed (see HERMANSEN 1978). The most accessible texts of Notitia and Curiosum are those provided by NORDH 1949. A comparable work for Constantinople is available in SEECK 1962.

COINS

The representation of buildings on commemorative coins is a valuable, albeit small scale, pictorial source. Comparison may be made with surviving structures such as the Temple of Pius and Faustina in the Forum Romanum or the Colosseum. Information may be supplied for lost buildings such as the Temples of the Deified Augustus or Trajan. Details of missing features may also be supplied, such as statues in front of temples, adorning entertainment buildings or standing in open spaces (for example, the statue on Trajans Column or the equestrian Statue of Domitian in the Forum Romanum). Considering the small size of coin representations, their artistry and accuracy, however stylised, is often remarkable ().

For collected reproductions of coins depicting buildings see NASH 196162; FRUTAZ 1962, Pl. 87; HILL 1989; STEINBY 199399.

INSCRIPTIONS

It has been very approximately estimated that some 300,000 inscriptions survive from the Roman world as a whole, of which over 50,000 have been found in Rome (these figures are ever-increasing, see KEPPIE 1991, 9; CLARIDGE 1998, 32). Every public building erected in the city bore an inscription advertising the identity of the builder and, where appropriate, the dedication. These contributed to republican lite competition and the advertisement of family ( gens ) success in war and public office. Emperors played this game on a massive scale, sometimes in competition with their predecessors, and the senate used epigraphy to honour the princeps . Individuals employed epigraphy to perpetuate after death their achievements in life. Predictably, the thousands of funerary inscriptions have been employed by scholars to study demographics and social structure, but there are well-recognized pitfalls, not least of which is the bias towards the wealthy who could afford the stone and masons services.

Inscriptions from Rome are principally catalogued in Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum ( CIL ), volume 6 and supplements, and Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae ( ILS ). New finds are published through the annual numbers of LAnne pigraphique ( AE ). Specialised collections have also been published, for example inscriptions pertaining to gladiatorial games in Rome (SABBATINI TUMOLESI 1988). In general see KEPPIE 1991.

FORMA URBIS ROMAE

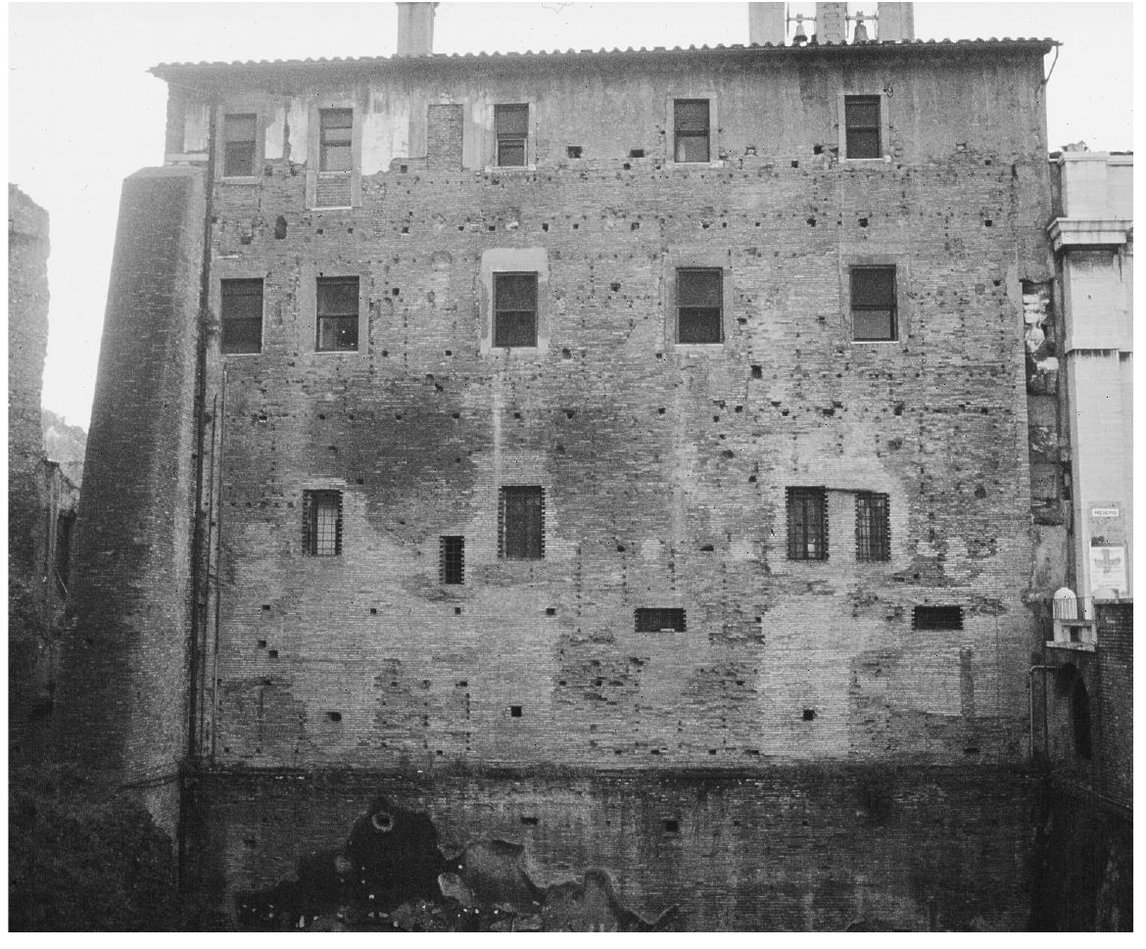

The Forma Urbis Romae ( FUR , a modern title) was originally carved on the veneer panels (north-east facing wall) of the south corner room of the Templum Pacis ( regio IV). It was carved in situ on 151 veneer slabs of Proconnesian marble attached to an 18 by 13 m wall, which still stands (). The first fragments were found in the 16th century, some of which have been subsequently lost, but survive as drawings. More pieces have been found in later excavations up to the present. Surviving fragments (1,163 pieces) and drawings make up 20% of the map area, but only 10% can be placed in identifiable positions. A numbering system for fragments was devised by Carettoni et al and this has been followed by later publications (CARETTONI 1960; RODRIGUEZ-ALMEIDA 197071; 197576; 1977; 1981; 1983; STACCIOLI 1962; TORTORICI 1988). The original locations of pieces may be identified by a number of methods:

- the carved detail of recognisable building plans, eg Largo Argentina temples;

- surviving ancient street lines, eg Clivus Suburanus/Via in Selce;

- building label inscriptions, eg Basilica Ulpia, Ludus Magnus;

- positions on individual veneer panels (ie edges, peg-holes);

- the coloured banding of the marble and pink fire markings;

- breaks and joins (ie normal jigsaw methods).

: The wall of the Templum Pacis on which the Forma Urbis was displayed. Brick-faced concrete with peg-holes for the attachment of marble veneer panels (Photo: editors).

The scale is approximately 1:250. A broad date of AD 205208 is given by the presence and absence of known buildings (eg the Severan Septizodium is present; the Basilica of Maxentius is absent). A narrower date bracket is provided by an inscription on the map labelling an Aventine building with the joint names of Severus and Caracalla (Fragment No. 42b, e: SEVERI ET ANTONINI AUGG NN). This Severan plan probably replaced and revised a Flavian predecessor.

Conventions: The carved details were originally painted. All the buildings, public and domestic, were represented in ground plan. Some public buildings are perhaps rendered in more careful detail at a slightly larger scale. This may be especially true of buildings restored after the Commodan fire by the Severi (eg Templum Pacis), and of new Severan edifices (eg the Septizodium with its massive label).

Specific conventions are used for:

| aqueducts |

|