My thanks are due to those who have faced the rigours of this subject and whose books I have mentioned, and also to the following for much help and kindness: Monsignor Hugh OFlaherty, Father Anthony Kenny, of the English College, Father Alfred Wilson, of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Major Dieter de Balthazar, of the Swiss Guard, Dr Angelini, of the Museum of Rome, Comm. Marcello Piermattei, OBE, Superintendent of the Non-Catholic Cemetery, Dr Guido Ricci and Dr Zaccardini Mario, of the Commnissiariato per il Turismo, Rome, and Dr Luciano Merlo, of the Ente Provinciale per il Turismo, Rome, Professor Ward Perkins, of the British School in Rome, and Messrs Longmans, Green for permission to quote from The Shrine of St Peter, Sir Alec Randall and Messrs William Heinemann, for permission to quote from Vatican Assignment, the Maryland Historical Society for the photograph of Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte, Miss Margaret R. Scherer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Messrs Glyn, Mills and Co, for the sketch of Charles Mills by the Count dOrsay, and to their Archivist, Mr S. W. Shelton, without whose help I should have been unable to solve the enigma of Charles Andrew Mills. My thanks are due in full measure to Mr D. H. Varley, Chief Librarian of the South African Public Library, Cape Town, and to his skilled and obliging staff.

H.V.M.

I am obliged to Mr E. C. Kennedy of Malvern College for pointing out the doubtful consolation that in the first edition of this book I erred with many distinguished authorities, including the Encyclopaedia Britannica, in repeating the Augustus legend in connection with the Julian reformed calendar. This I have altered on page 117.

H.V.M.

CHAPTER ONE

From a Roman balcony the noise of Rome walking about Rome-breakfast near St Peters the Fontana di Trevi the growth of a superstition

1

T hose of us who had not fallen asleep glanced casually down at the Alps. They lay beneath our wings like a model in a geological museum, and though it was July, many a summit was still white.

There comes over one sometimes a sense of the wonder and fantasy of this age, and, as I adjusted my chair to a more comfortable angle, I thought how preposterous it was to be speeding through the sky to Rome, many of us unaware of the great barrier which awed and terrified our ancestors. While I looked down, trying in vain to identify the passesthe Mont Cenis, the St Gothard, the Great St Bernard and the Little, and the famous Brennera series of pictures flashed through my mind.... Hannibal and his hungry elephants, Charles the Bald dying in the Mont Cenis, the Emperor Henry IV hurrying through the blizzards of January, 1077, to make peace with the Pope, while the Empress and her ladies were strapped into ox-hides and let down over the frozen slopes like bundles of hay.

Would you like a glucose sweet or a peppermint? asked the air hostess, as we crossed the Alps.

The feelings of many centuries of Romeward bound travellers were expressed in a sentence by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, when she wrote from Turin in 1720. I am now, thank God, happily past the Alps. Even in her day, when the Grand Tour was beautifully organized, the passage of the Alps was full of danger or at least of apprehension. It was usual for the coaches to be unbolted and sent over on the backs of mules, while the travellers, wrapped in bearskins and wearing beaver caps and mittens, sat in armchairs slung between two poles and were carried over the pass by nimble mountaineers. Montaigne, who went to Italy to forget his gall-stones, was carried up the Mont Cenis, but on the summit was transferred to a toboggan: and in the same pass Horace Walpoles lapdog, Tory, was seized and eaten by a wolf. Even while these random thoughts passed through my mind, we had left the Alps far behind us, and it was not long before we were fastening our belts for Rome.

The drive from the airport into Rome was long and dreary, but all the time I was thinking with pleasure of the room with balconys to which I was speeding. For weeks I had lived with a mental picture of this balcony, though I had never seen it. There might not be bougainvillaea, I told myself, but no doubt there would be geraniums in pots; and I would stand there in the evening and watch the sun setting behind St Peters, as so many had done before me, while the swiftswould there be swifts in July?would cut the air with cries which every Roman child knows means Ges... Ges... Ges!

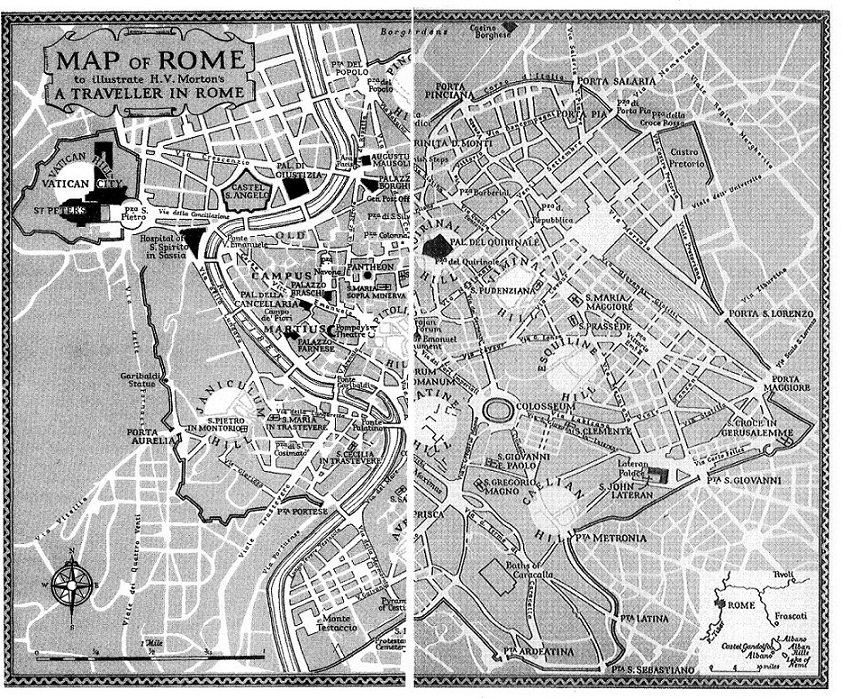

We saw the ruins of an aqueduct limping across the landscape, and though I recognized it from photographs I had seen, I could not give it a name. I was finding out in the first ten minutes that a visit to Rome is not a matter of discovery, but of remembrance. We dashed through the outer suburbs, where blocks of stark concrete flats, the modern descendants of the Roman insulae, but apparently a good deal more solid and upright, stood amongst piles of rubble; then we passed through the Aurelian Wall by way of a turreted gate and joined a great press of green tramcars and buses, while illustrations from books, the subjects of postcards from friends, and the pictures upon the walls of old-fashioned vicarages, sprang into life all round us. Here and there we recognized an obelisk and here and there a fountain.

I transferred myself and my luggage to a taxi and sped downhill through a hot, golden afternoon towards my room and balcony. I caught a glimpse of a great number of people drinking coffee under blue umbrellas in the Via Vittorio Veneto, then we swerved into a side street and drew up before a rather severe archway.

2

Could this be my balcony? Was this the place I had been dreaming about for weeks? I could see nothing but the building opposite, which had been carelessly splashed with brown limewash many years ago. From its windows faces looked at me with the hostile curiosity of those who observe a new boy. Men wearing odd little sculptors caps made of newspaper were repairing the roof. I could see shops, restaurants, a barbers shop, and a quick lunch bar where food simmered in pans in the window, together with plates of peaches and jars of olives and artichokes. At the entrance to a subterranean vault a hunchback cobbler sat gnomelike, with his mouth full of nails, which he swiftly transferred to the sole of a shoe he was repairing. I turned away disappointed, another illusion gone, for this was not the balcony which more fortunate writers always seemed to find, with its romantic view of St Peters.