BRUCE WARE ALLEN

TIBER

Eternal River of Rome

ForeEdge

ForeEdge

An imprint of University Press of New England

www.upne.com

2019 ForeEdge

All rights reserved

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Allen, Bruce Ware, author.

Title: Tiber: eternal river of Rome / Bruce Ware Allen.

Description: Lebanon, NH: ForeEdge, an imprint of University Press of New England, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018022308 (print) | LCCN 2018031668 (ebook) | ISBN 9781512603347 (epub, pdf, & mobi) | ISBN 9781512600377 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Tiber River (Italy)History. | Rome (Italy)History.

Classification: LCC DG975.T5 (ebook) | LCC DG975.T5 A45 2019 (print) | DDC 945.6/32dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022308

CONTENTS

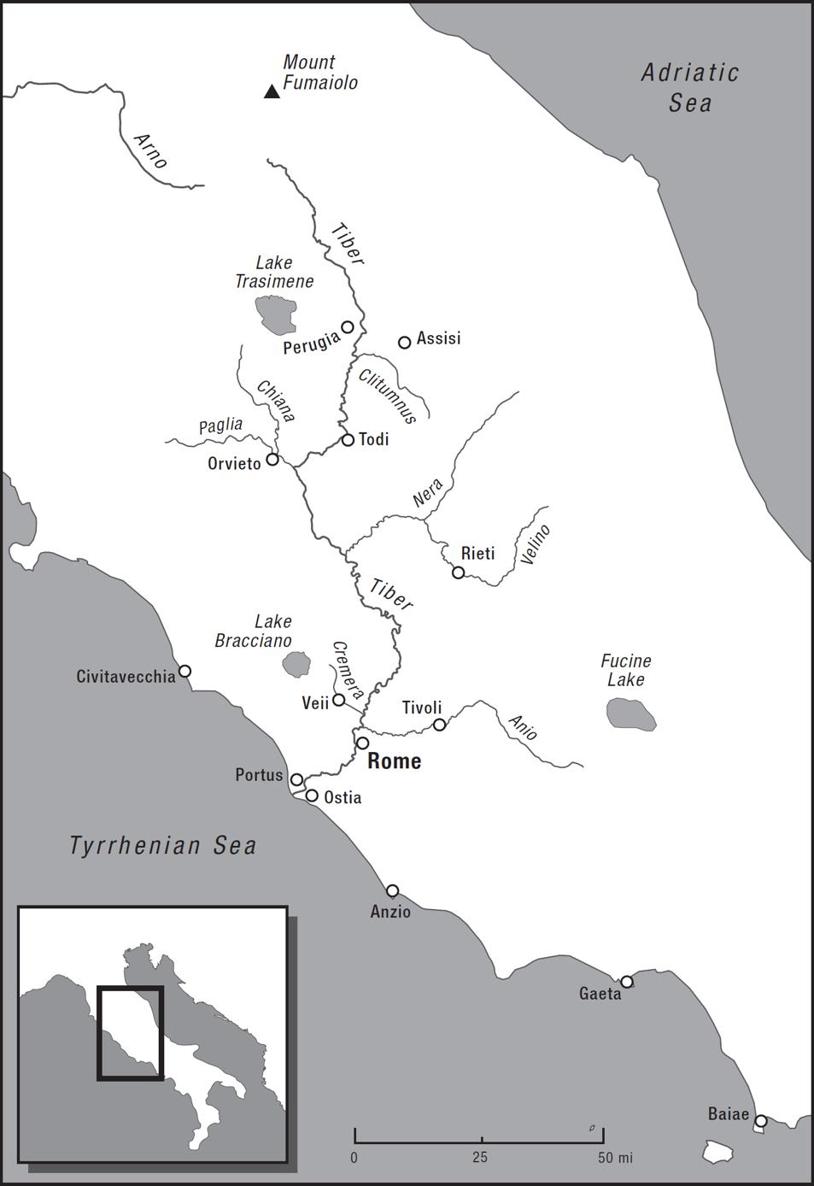

THE TIBER AND SOME TRIBUTARIES

INTRODUCTION

Ive trod the Forum and I have scaled the Capitol. Ive seen the Tiber hurrying along, as swift and dirty as history.

Henry James to his brother William, 1869

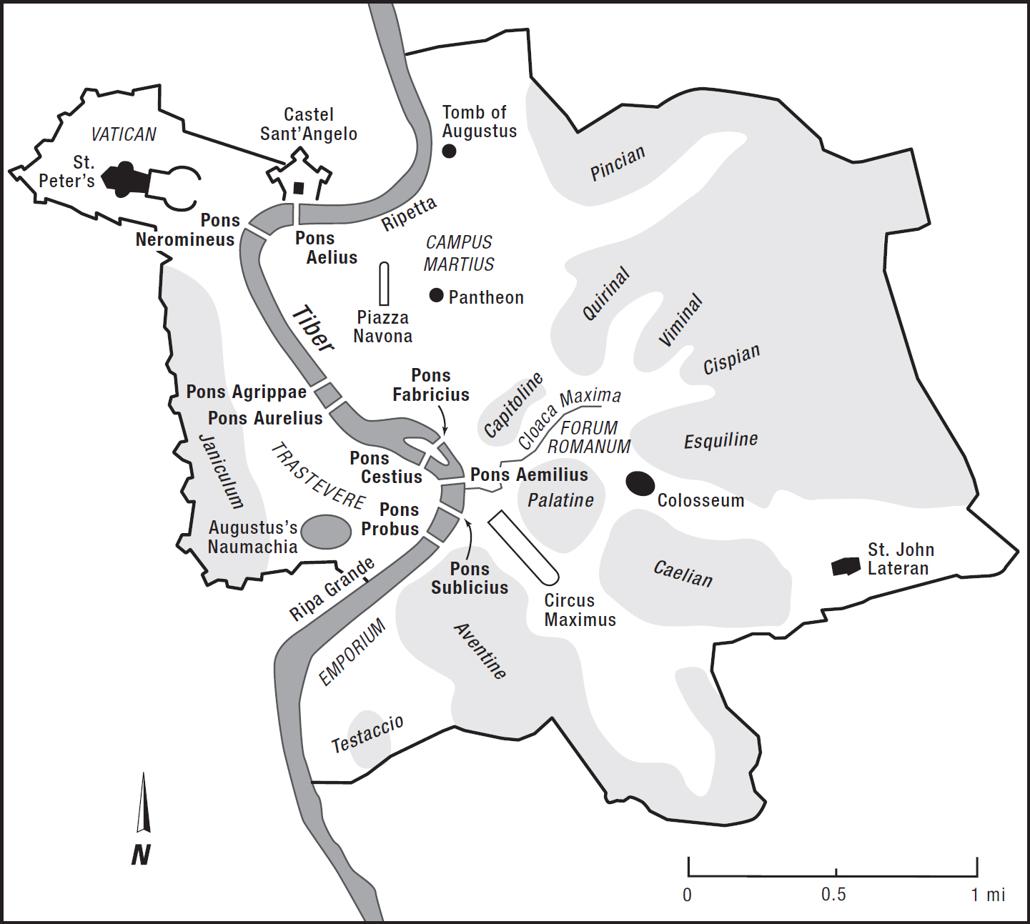

James wrote at a time when Rome was still vitally connected to the Tiber, when small boats, lighters and barges, still floated olives and wine and grain downriver from Tuscany and Umbria to the curved baroque white marble of the Ripetta wharf; or more exotic goods were pulled upriver with aid of oxen and against the current, from river mouth at Ostia to the wharves and quays of Romes city center at the Porto Leonino and to the Ripa Grande near Porta Portese. Once arrived, crewmen and stevedores lounged as agents sought out buyers, and only then off-loaded the cargo and watched the goods disappear into the business of the city, just as their predecessors had done for over two thousand years.

In less commercially active stretches along the river, mud and river grass and clay and bulrushes, and occasional sand, sloped down to the water. On hot days, children and other idlers could wander down and cool their feet in the running water and watch the scenery, just as their predecessors had done for centuries. Painters could still find for their canvases good views of aging palaces and ancient ruins against the river, symbols of change and decay.

The year following Jamess visit, everything had changed. In December of 1870, the river rose and flooded the city, as the river had done for millennia. Every time, Rome had grieved and endured, sometimes talked about ways of eliminating this problem, and inevitably sighed and shrugged and moved on. This time, however, things were different. Modernity had come to Italy. The various states had been unified under one government, the king of Savoy, Victor Emmanuel, chosen as head of state, and Rome, the new capital, was not going to be subject to the whims of a temperamental river. For the first time in three millennia, in the ongoing struggle with this part of nature, something would be done.

It was something of a new attitude. Early Romans had been deferential to

The attitude was not entirely wrongheaded. The river was, first of all, a source of life. It provided fish to eat, water to drink and grow crops with, a medium for transporting trade goods.

Water was also a barrier against hostile neighbors, just as it was to be for Venice and the Netherlands. For a traveler wandering the city today, the swamps and streams and high slippery banks surrounding the seven hills are difficult to imagine. To get to the Romans high ground, the enemiesEtruscans, Gauls, Sabineshad to pass over the river or through a mephitic swamp known only to locals. Sabine warriors, retaliating for the abduction of their women, made do with the help of Tarpeia, a local girl who showed them how to negotiate the narrow and slippery approaches to the city. She was killed for her troublesthe Sabines had no love of traitorsbut the attack failed regardless. Janus, god of gates and doors, a friend of rivers and Rome, sent up a geyser of boiling water to ward the Sabines off.

Later visitors besides James, beguiled by years of schooling in Latin, Roman history, and art, found that the reality did not live up to the dream. The Englishman Richard Lassels in 1670 or so wondered to finde it such a small river, which poets with their hyperbolical inke had made swell into a river of the first rate.

He wasnt alone. A disappointed David Garrick wrote in 1763: It is strange that so much good poetry should be thrown away upon such a pitiful River; it is no more comparable to our Thames, than our modern Poets are to their Virgils and Horaces;

(At the same time, Hazlitt went on to say that St. Peters is not equal to St. Pauls [in London], which suggests some considerable bias, or discomfort on his trip. Presumably he liked the food... )

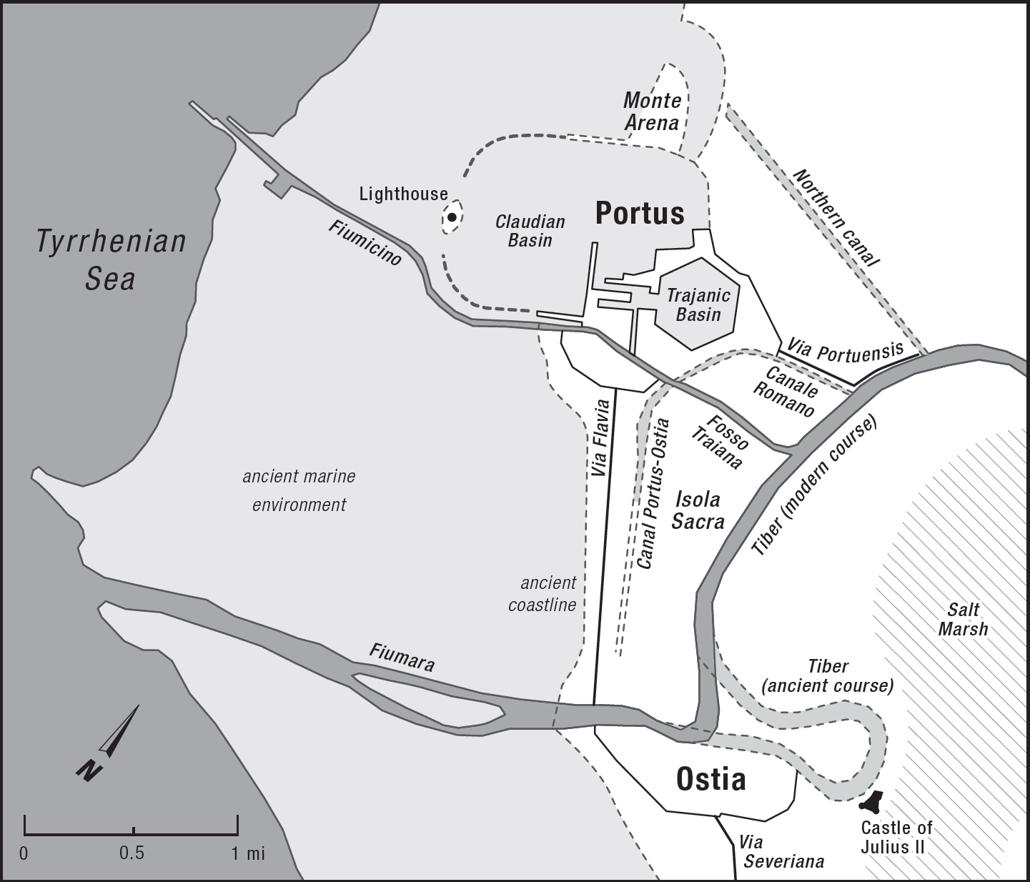

Robert Burn (the English classical scholar, not Burns the Scottish poet) in 1871 dismissed the river as too large to be harmless, too small to be useful. By no means was it too small to be useful, and for centuries, of all the roads that lead to Rome, the Tiber was the most important. At the height of the empire, a column of barges weighted down with grain and wine stretched the full eighteen miles from the wharves at Rome to the rivers mouth at Portus and Ostia, where cargo ships from across the Mediterranean and beyond brought the food that fed a million people, and the spices from India and silks from China that diverted those who could afford them. Traffic was heavy enough that the emperors toyed with the idea of carving a straight parallel causeway to Ostia to help ease some of the congestion.

They might have done so, too, except for religious scruplewater, claimed the naysayers, is powerful and, like cats, roams where it wants, andalso like catscan make trouble for anyone who tries to get in its way. When the emperor Nero fell ill in AD 45 and was near death, his more pious subjects attributed the calamity to his having bathed in the source of the Aqua Marcia; even the emperor cannot profane sacred water, springwater still less, and least of all water that exits the ground at a bracing forty-six degrees Fahrenheit.

It was the river that refused to drown Romulus and Remus, ensuring that they survived long enough to found an empire. It was while engaged in religious observations at the riverside that Romulus was finally transported to a better place. (Or so the story goes. Others claim that he was killed and dismembered by accompanying senators, who carried the pieces away under their cloaks.)

The Tiber became the earliest symbol of Rome, at least as powerful as the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus. Other nations have lifted from it. The fledgling capital of America for years had a tributary of the Potomac called Tiber Creek (which was in fact a small, slow, and decidedly dirty stream that ran through Rock Creek Park and has long since been paved over by Connecticut Avenue, its presence unsuspected even to longtime residents, the answer to a trivia question). The river Tiber snakes through the city on its way to the sea; it separates the bulk of civil Rome from the Vatican. Protestants embracing the Catholic faith are said to be crossing the Tiber.