Contents

Guide

THE

ETERNAL

CITY

A HISTORY OF ROME

FERDINAND ADDIS

T HE E TERNAL C ITY

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2018 by Ferdinand Addis

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition November 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-68177-542-5

ISBN: 978-1-68177-599-9 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

To my mother, Noonie, whose Rome led to mine

CONTENTS

Common practice now in academic history books is to designate years before and after the year not as years BC and AD but rather BCE and CE , standing for Before the Common Era and After the Common Era.

The reasons for this are broadly commendable: historians dont want to impose a Christian-centric dating system on readers who may belong to any religion or none. They are uncomfortable with the religious claim implied by Anno Domini.

In another context I might very well have followed this convention. However, for this book, various considerations urged me towards the traditional AD and BC . This book is, above all, about the ways humans have located themselves within history. It is not an academic book, nor is it concerned with history as a quasi-scientific discipline. It makes no claim to abstraction, or impersonal authority. It might question the idea that any era could be common to all. This is a book about people, and their experiences and prejudices and beliefs, the myths to which people have clung.

No solution is perfect, therefore. But AD and BC , as well as being familiar, is the system that most of the subjects of this book would have recognized. The claims implied in those abbreviations are claims to which most of the subjects of this book would have assented, however they might strike us today. I have located my subjects in history using, so far as possible, the landmarks they might have used themselves.

(Another candidate dating system would have been AUC Ab Urbe Condita years elapsed since the notional foundation of Rome in 753 BC . However, even the ancient Romans very rarely used this system. They usually dated years by the names of the men who served as consuls, or by the regnal years of emperors, and I thought even for the most committed reader that might be asking a bit much.)

Romulus and the foundation of Rome

_________

753 BC

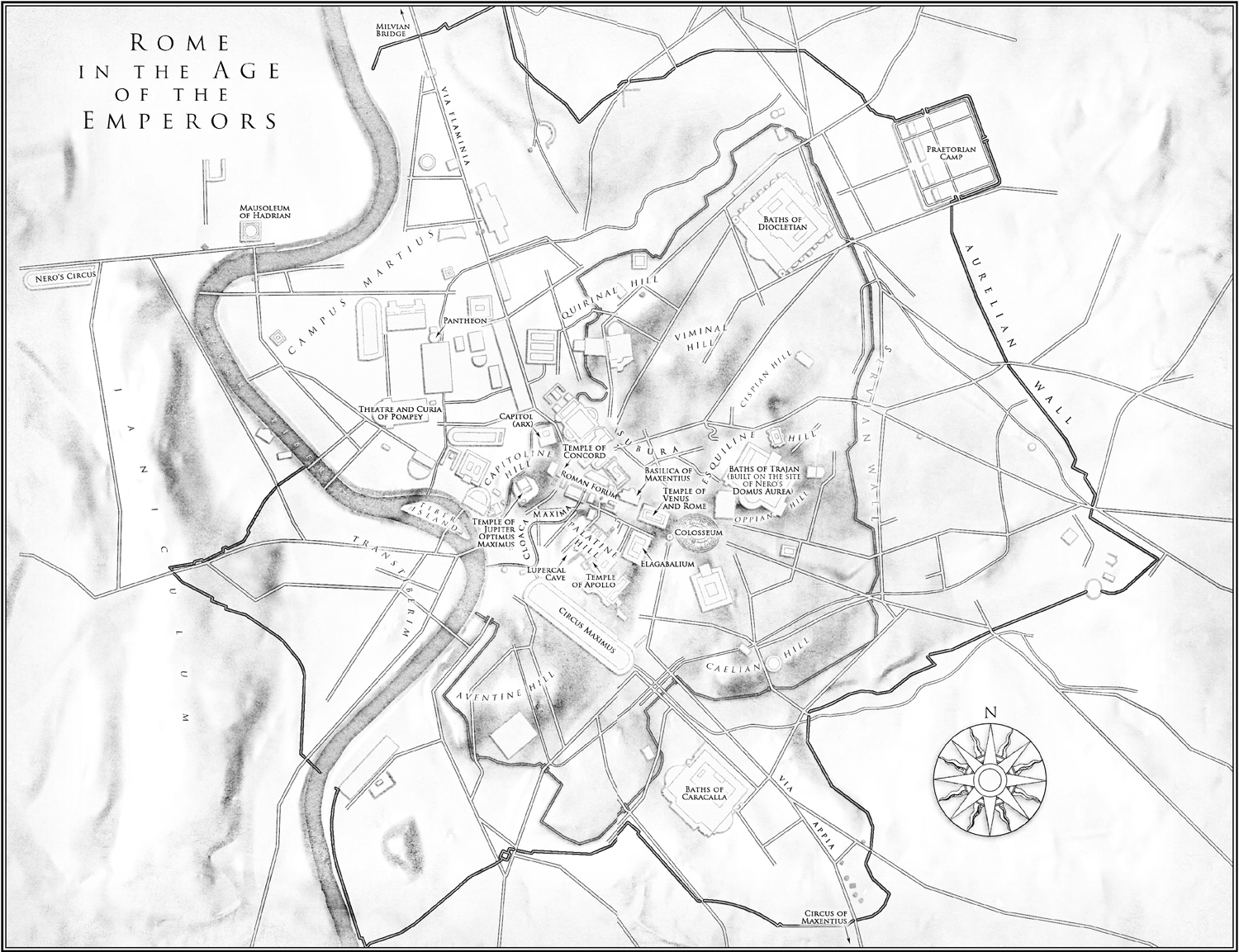

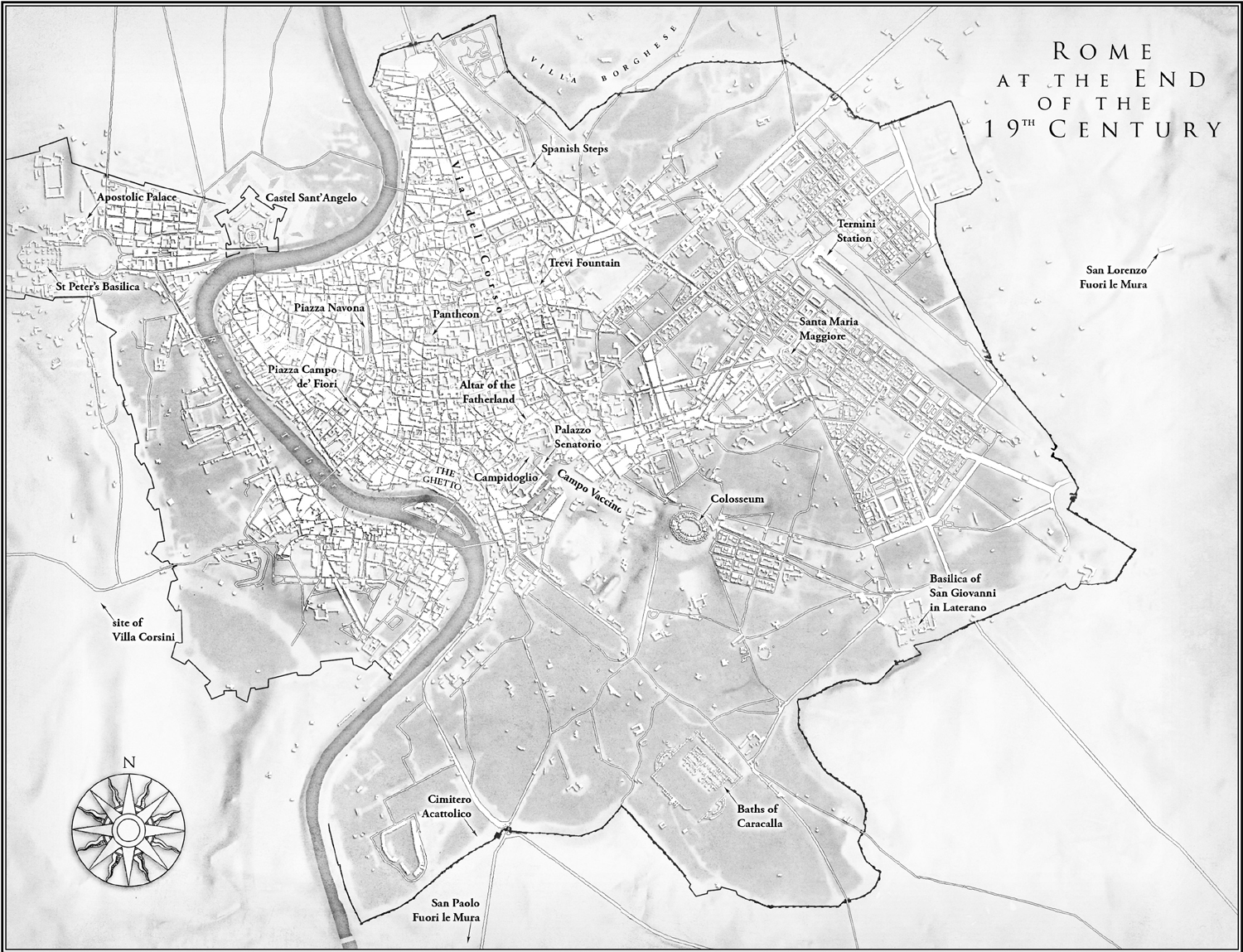

I N THE MIDDLE of a fertile plain, halfway between the mountains and the sea, a river flows between a cluster of low hills. Seven? It depends on how you count them.

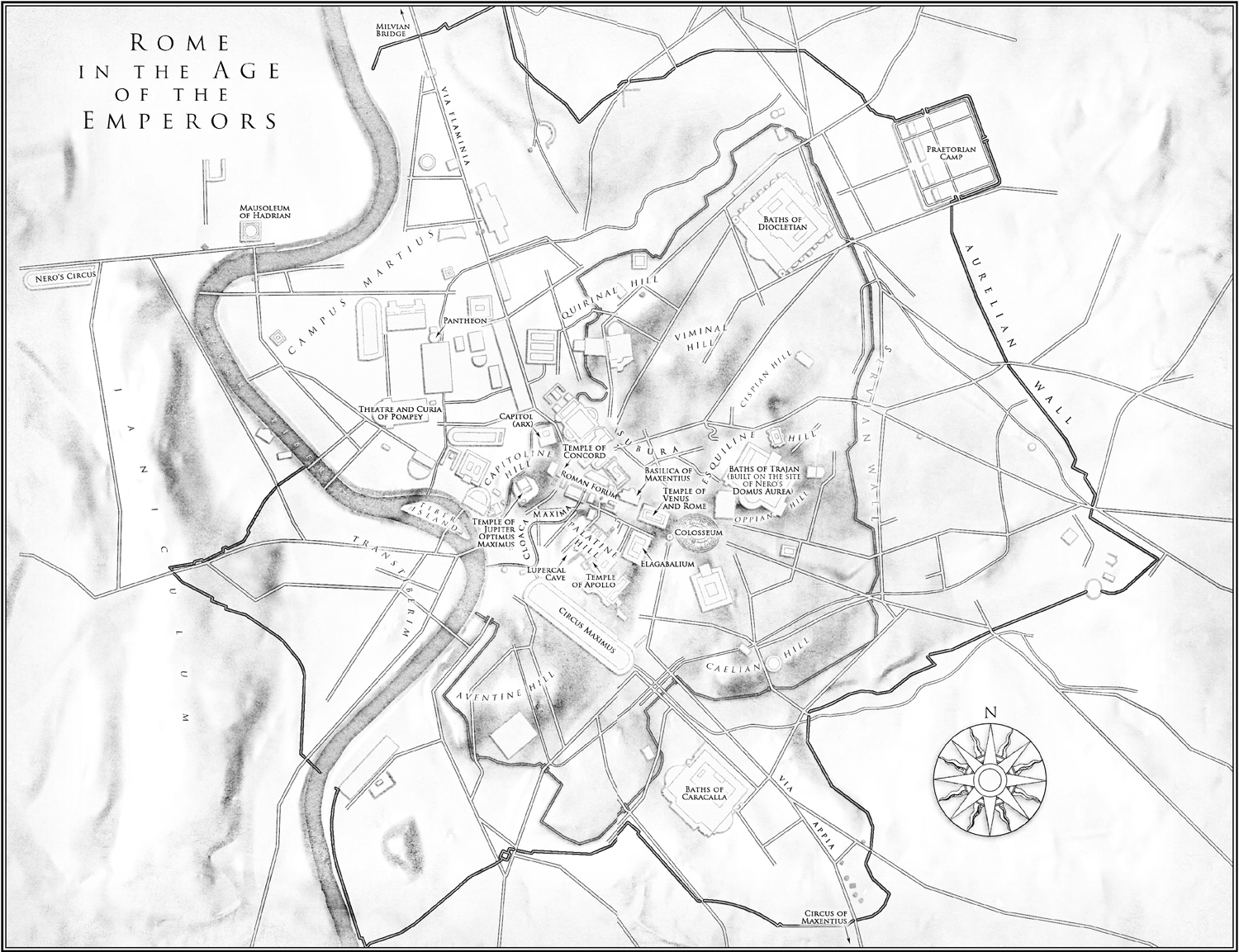

Three hills stand along the river: the Palatine, whose broad back will one day groan under the weight of imperial palaces. The great hump of the Aventine, a hill for rebellious plebs and foreign gods. Last, the Capitoline, craggy and steep, the hill that will be the sacred citadel of a city called Rome.

From the high ground away to the north, three ridges extend southward like long fingers: Quirinal, Viminal and Esquiline, their bare tops not yet disturbed by the rush of motorcars and movie stars and government ministers, of trains being made or not to run on time.

The Caelian hill makes seven, rising above a waterlogged hollow where, many centuries from now, the air will tremble with the roars of the Colosseum crowd.

But why stop at seven? What of the minor summits, the Oppian, the Cispian, the Velian ridge? What of the Janiculum on the far side of the river, the invaders hill, where Garibaldis redshirts will shed their blood for Rome? What of the Pincian, with its Napoleonic gardens? What of the ground that will one day be Testaccio, a carnival hill, heaped from the shards of broken oil jars? What of the pilgrims landmark, Monte Mario? What of the Vatican hill, where Christians will drive out pagan soothsayers to build, on their own tombs, the foundations of an all-conquering church?

On every side, the future presses in upon the empty landscape. There is no ridge, no valley, no wrinkle in the earth that will not one day witness great events. Each hill, each hummock, each pool, each patch of grass waits, silent, to assume its name, to take its place in history.

* * *

The River Tiber flowed down from the mountains, carving its way through the land, reed beds and water meadows and banks shaded with oak and pine, strawberry trees, the shivering leaves of tall poplars. These were the gifts of the river god, shaking out his watery locks over the plains of Latium.

This was a country peopled by gods and spirits only: nymphs in forest pools; satyrs with sunburned skin; two-faced Janus; almighty Saturn; Picus, the prophetic woodpecker; wild-eyed Faunus, tangling his horns in dark thickets.

And then, one day, Father Tiber in his foaming flood carried downstream a pair of human boys. And Roman history began.

They came ashore in winter, at the foot of the Palatine hill. The flood waters of the Tiber bore the boys up gently, washing them towards land until their makeshift cradle tangled with the roots of a spreading fig tree. There, in the ordinary way of things, they should have died.

But a she-wolf, living nearby in a cave under the Palatine, smelled their human scent on the breeze. Soft-footed through the mud, she sought them out. And though she was hungry, and the winter hard, she recognized in the children something of the divine. Curling around the twins, to offer them her teats, the wild she-wolf suckled them.

The image of the twins and the wolf became a symbol of Rome. It was a moment outside history, an image that needed no before or after to give it power. The wolf was as eternal as the gods, a fierce and paradoxical archetype, savage but protective; likewise the twins, naked and vulnerable, but fat with infant strength and infant appetite.

The twins and the wolf were timeless and divine. But the twins were also human. And to be human is to have history, to be burdened with it, weighed down with chains of cause and consequence. The storytellers who passed down the tale of the two miraculous boys could never resist the urge to add context, to give them a past and a future, to ask and answer those worldly mortal questions: where had they come from? Where were they going to? The twins, like the seven primaeval hills, were given names: Remus and Romulus, the founders of Rome.

The culture of ancient Italy was shaped, above all, by Greeks. Greek stories were well known in Rome, especially those stories that had been told in Greeces great epic poems, the Odyssey and the Iliad . The mythical chronology provided by those poems was the context into which Romulus and Remus would be made to fit.