Authors Note

This is a work of fiction, but many members of its cast were as tangible as Peenemnde itself. I have attempted to write actual persons in character insofar as is possible, but I take all responsibility for errors, anachronisms and misinterpretations.

The leading protagonist, Otto Fischer, is entirely a product of my imagination, as are Friedrich Holleman, Kaspar Nagel, the named junior staff of Peenemnde East and all other named Trassenheide and Luftwaffe Berlin characters including, regrettably, Douglas von Bader. No liaison and training office of the Kriegsberichter der Luftwaffe existed in Berlin or elsewhere, though field units were attached to each Luftflotte and individual Flieger divisions.

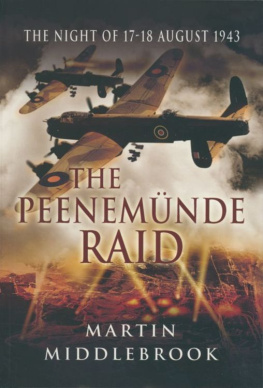

In contrast, the named hierarchy and technical staff of Peenemnde East Dornberger, von Braun, Thiel, Schilling, Rudolph, Schubert, Stahlnecht, Steinhoff, Kurtzweg and the superabundance of Riedels will be very familiar to students of the prehistory of space flight. Furthermore, the major events described the British air raids of 18 and 23 August 1943, the interminable debates on A4 production quotas, the post-raid handover of production to the SS under Brigadefhrer Kammler and its eventual relocation to the infamous Mittelwerk facility in Thuringia, the Zanssen-Stegmaier affair, Klaus Riedels communist past and the tentative, clandestine attempts by senior staff at Peenemnde to interest the Allies in their work are all a matter of record, though for dramatic purposes I have brought forward the genesis of the latter by a full year. The initial, verifiable initiative (of both Dornberger and von Braun, via the German Embassy at Lisbon) occurred only in the latter part of 1944. However, I do not believe that my acceleration of their treachery exaggerates their determination that the work of Peenemndes engineers should survive the regime.

Walter Thiel died with his family during the raid of 17/18 August 1943, when the air raid trench in which they were sheltering collapsed. The subsequent shooting of his corpse is entirely my fiction, and on that point Generalmajor Dornbergers reputation stands entirely unsullied. Finally, there was in fact an inmates band at Trassenheide camp, though liberties may have been taken with regard to its repertoire.

Klaus Riedel did not, to my knowledge, ever resist or even know of efforts to put out feelers to the Allies. However, he died in mysterious circumstances a year after the events portrayed here: precisely at the time those initial approaches were being made. His body was discovered in the wreckage of his car, close to the Peenumnde site; investigators found no obvious cause for the crash. Had he lived, there is no reason to suppose that he would not have joined those of his colleagues who were recruited into some might say inaugurated the embryonic US rocketry programme.

My premise in relocating to 1943 the future actions of Peenemndes principals gains some credibility from a further episode. Both Riedel and Werhner von Braun were arrested by Sicherheitsdienst in March 1944 and held for almost two weeks in solitary confinement at Stettin. Surreally, the aristocratic von Braun was accused, like Riedel, of communist sympathies. He was told, furthermore, that informed witnesses had testified that he was wholly committed to the realization of space flight, rather than to Peenemndes weapons programme: a rare occasion of Himmlers febrile imagination blundering into the or a truth. Von Braun and Riedel were released following Dornbergers frantic manoeuvrings via contacts in Abwehr and Reichsminister Albert Speers representations to Adolf Hitler.

Chapter One

Tired, he pressed his face against the window and stared into the flat, colourless sea, following it out until he couldnt be sure that it wasnt sky. A familiar horizon: playful, shy, almost always a matter of guessing where one thing became another, where breathing became drowning.

The Baltic: the road of seabirds tears. To the boy it had been the world itself, a grey world, more shades of it than to be found in a Luftwaffe depot. A violent place, sometimes; painters chased its elusive light, sailors ran before the dark, immediate squalls, but his memory had calmed these extremities, faded them to safer mid-tones. He recalled the air and water only at their most guileless, the soundless calms that seemed to go on forever, soothing, deceiving. A small, still world of indistinct boundaries, marked only by the graves of those lost within it.

No dead reckonings today . He blinked himself awake, lit a cigarette and felt the pain returning as his face departed the cool glass. The young obergefreiter sitting opposite glanced enviously at the smoke but avoided looking directly at him (most men in uniform did, hed observed). It seemed churlish to cough, but he drew too deeply into his damaged lung, more smoke where it wasnt needed. When his eyes cleared, he managed a shrug and leaned forward to offer the thing to a man who could use it. A slight nod for thanks: the economy of manly pity.

The train slowed, its ageing axles squealing hideously as they passed through Bansin-Heringsdorf-Ahlberg. Even across two decades, his young proletarians prejudices held firm: a cold, self-conscious place, guaranteed its trade even in thin times, smugly secure in its reputation as the resort of Kaisers. Too scrubbed still, he decided: too zimperlich , obscenely out of its time. His bored minds eye drifted across the quaint, stolid bderarchitekturs whitened walls and regular red roofs, and imagined it atomized, all future histories truncated into the moments an eighty-eight millimetre would require to traverse its mounting and put one through the collective, rustically shuttered window.

A sin, even to think it , his mother would have said, but the towns had earned some ill will. She had been a drudge here, cleaning their hotels high-ceilinged bedrooms and ornate water closets, bearing the condescension of under-managers, head maids, guests and even house-boys, earning half a pittance for hours that a clock would have jibed at, and still, not a single deposit of spite or resentment had stained her stoic soul. Shed been Old Germany: devout, hoping only for the balm of her covenanted portion, thinking no ill of her many judges. A wholly admirable woman, and whenever he was tempted to wish for more of her nature in himself he recalled her hands and knees. Cautionary tales in purple, theyd surrendered years before the rest.

His eyes stared at nothing, stinging yet refusing to close. Since departing Berlin he had known it would be like this, the memories falling like old newspapers that a rotting cord had let slip. To make sense of the summons required that he question it, and questions had an inconvenient way of shaking out the past, of raising dust. He glanced down the length of the carriage, seeking distraction. It was at least as old as he, its nominal seating arrangements overburdened by a press of bodies, loaded according to the convex wall principle of military redeployment. His own space, staked out with luggage and rank before the majority joined the train at Swinemnde, was relatively generous, but his maudlin, self-indulgent mood saw it as a close confinement. The narrow sweep of his vista, the crowd of uniforms, the nicotine blur and shared weariness of war, all of it heightened a sense of passing into he strained to define it, but it eluded him once more, leaving only the faint peal of things misplaced and lost. The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show, of mouthd graves will give thee memory

He shifted, dislodging dead Englishmens unwelcome reveries. A stabbing nerve took their place, reminding him that he had sat still for too long, one of his new regimes most pronounced Donts . He began to move his right hand in small figures of eight, working the flexors and extensors of his forearm, trying not to engage the bicep and deltoid until their turn came. The motion was immediately painful, but he persisted, willing it to become an unthinking habit, concentrating upon the wholesome view through the windows and the stale smells around him, on not grimacing.