This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1962 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

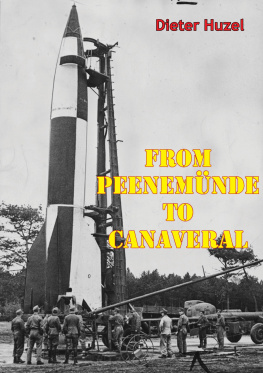

PEENEMNDE TO CANAVERAL

DIETER K. HUZEL

with an introduction by Wernher von Braun

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

TO IRMEL

THE WAY IT WAS

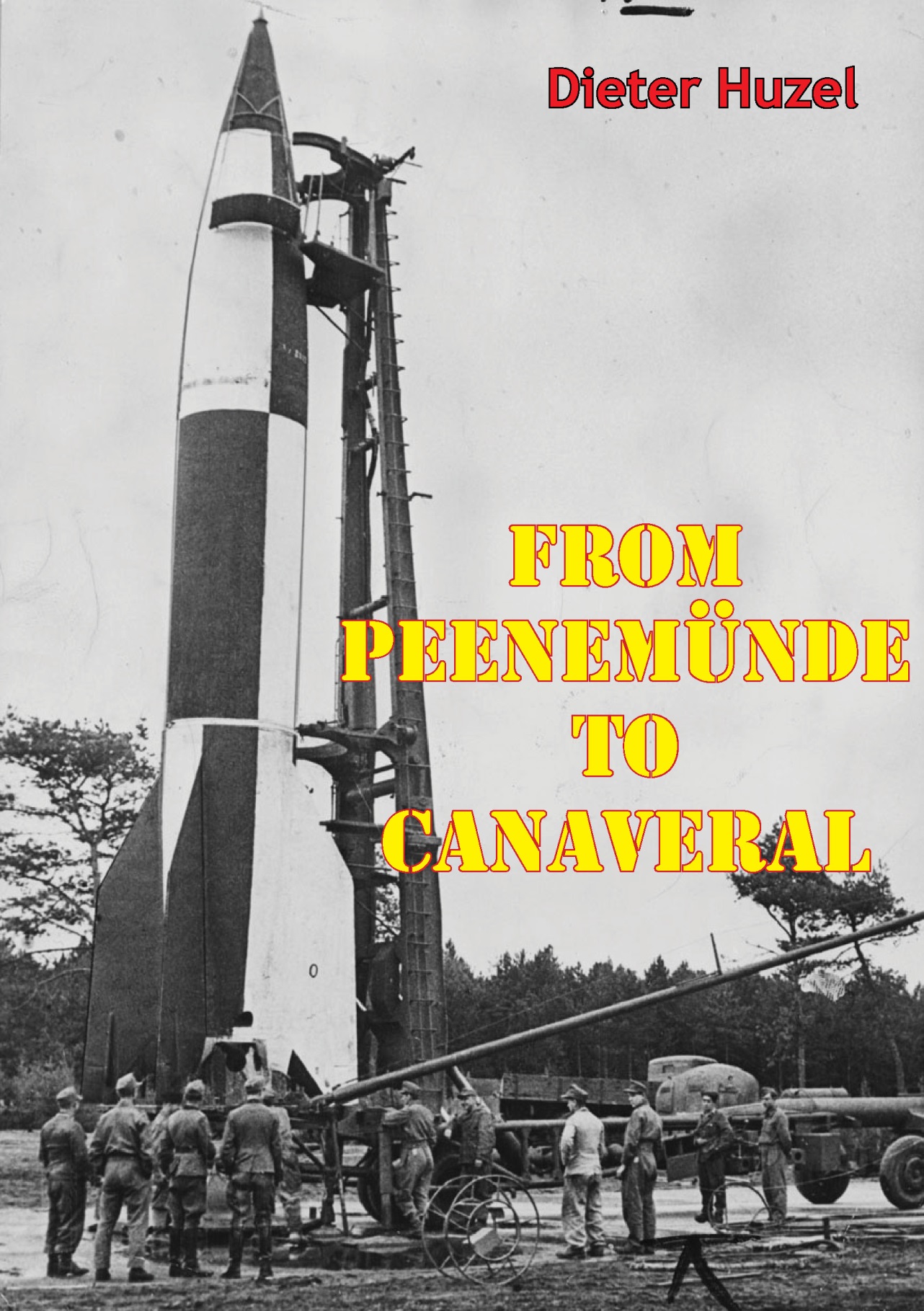

Twenty years ago, the first V-2 rocketor A-4 as we Peenemnde men called itwas launched. From these humble beginnings, rocket engineering has advanced to the threshold of space exploration. A good deal has happened in the intervening time, to the world and, more specifically, to the rocket. Ideas not even close to the drawing board then are now old hat or well along toward realization. The large guided rocket which first came to life on the Baltic island of Peenemnde before and during World War II now occupies a sizable portion of Mans thinking: As a weapon, as a tool for the exploration of cosmic space, as a vast new challenge to many branches of engineering and science.

Twenty years is a long time in the fast moving Age of Space. Peenemnde has become a legend; the A-4 a touchstone, a kind of intellectual prototype. But Peenemnde was a place , and the rocket was its product and where there are places and products there must be men. There was no magical waving of a scientific wand to create the A-4 rocket. It was the result of men working, working hard and with devotion to an idea which far transcended its imminent application as a weapon of war.

That is what this book is aboutthe men who made the large rocket a reality. It is told by one of those men, Dieter Huzel, who worked in all phases of the effortin the field, on the test stand, in administration. He saw Peenemnde at the height of its historic place, and he saw it crumble under the effects of war.

Much has been written about Peenemnde, but mostly by people writing from second-and third-hand information. Too much of this has been utter nonsense. It is time that a word was said about Peenemnde as it looked from the inside. And said by somebody in a position to knowsomebody who was there.

Quite probably, I might differ with some of the views and evaluations in the pages that follow. But then, maybe I would have been looking at things from a somewhat different viewpoint. And viewpoint is the very key to understanding human relations. But this I do know: The man who writes about Peenemnde here tells a first-hand story, and the only axe he has to grind is that of the truth.

And I think there is a great underlying truth, a lesson for all of us today in the story of Peenemndes rise and fall. Our contemporary newspapers are full of stories of missile and space rocket tests, of great successes side by side with heart-breaking disappointments. To the average citizen who hears how much depends upon the successful outcome of a particular launching, it must seem that with all this money and timehow can we still have failures? What most people do not realize is that in rocket engineering there is no such thing as a complete failure, that data is dataand each bit of data makes the next step more certain of success; that every new advance in technology, everything we accomplish in science and engineering is only the sum total of human effort. A rocket never learns what is wrong with it. It is the men who learn, the men who are building it. It was the men who made the A-4, and it is the men who are carrying on the job today.

So the proper story of Peenemnde is the story of its people; and in their struggle for success is mirrored the struggle of todays rocket men, in this country and, it may be presumed, in the Soviet Union as well. That, I believe, is the most important thing this book has to say.

What you read about Peenemnde in the following pages you may regard as the eye-witness account of a man who was there, for this is surely the most complete portrayal of life at Peenemnde that I have yet seen. The place is here: The streets, the buildings, the test stands, the sound of the waves breaking on the beach and of a mighty rocket engine filling the air with its window-rattling roar. The people are here: Struggling to keep equipment operating in the face of explosions, misfirings and air raids; trying desperately to accomplish their job in the face of ever-mounting odds, achieving ever-increasing success even as the means of achievement slipped from their grasp.

A man would have to have been there to recognize the accuracy of the picture presented here. And, of course, I was. These pages have brought Peenemnde vividly back to life for me.

This is the way it was.

WERNHER VON BRAUN

Huntsville, Alabama November, 1961

Peenemnde to Canaveral

1 THE ROAD TO PEENEMNDE

Launch switch to launch!

Key is on launch.

Launch start!

The final commands of the countdown had the staccato precision of rifle fire. Launch controller Albert Zeiler stared fixedly through the large window which provided an unobstructed view of the tall RS-1. With the closing of the launch key, a timer relay started ticking away. The liquid oxygen vent valve closed, and the little white vapor plume that had been floating gently from the frost-covered side of the missile was snuffed out.

The dozen or so people in the launch control center hardly breathed. Propellant tank pressurization would take 30 seconds. No one showed any emotiononly tension and apprehension. All eyes that could be spared from the launch control consoles peered with Zeilers through the thick double-mirrored window at the silent bird without.

Several hours earlier, the first light of dawn had gradually lifted the silhouette of the 65-foot high rocket from the harsh embrace of the floodlights. Moments before the myriad of workmen attending to the birds many pre-launch needs had scurried for cover as the wail of sirens and the blink of flashing red lights warned of the final moments of countdown.

Inside the half-buried concrete-reinforced blockhouse now all was silence, save for the steady click-click-click of the relay, the hum of electronics, final terse reports of pressure values building up in the rockets propellant tanks, and occasional anxious but reassuring remarks of a guidance engineer intently scanning the array of dials and signal lights before him. Those 30 seconds seemed like an eternity.

Tanks pressurized!

A small bright flame burst from the tail of the missile.

Pre-stage!

The wiggling flame grew, billowed and engulfed the launching pad. Zeilers sharp command was almost drowned out as the missiles roar slammed its way into the blockhouse. The noise rose to a deafening crescendo.

Next page