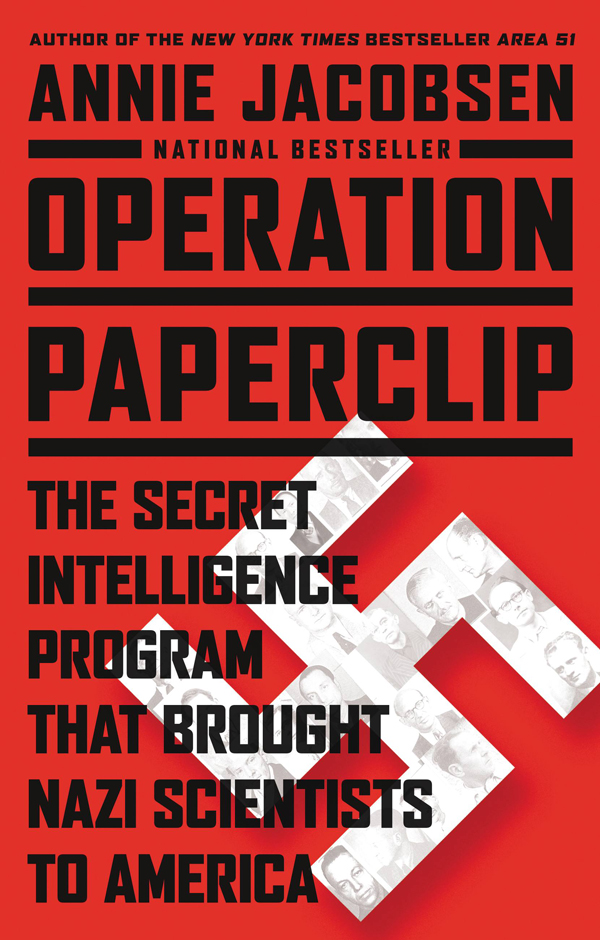

T his is a book about Nazi scientists and American government secrets. It is about how dark truths can be hidden from the public by U.S. officials in the name of national security, and it is about the unpredictable, often fortuitous, circumstances through which truth gets revealed.

Operation Paperclip was a postwar U.S. intelligence program that brought German scientists to America under secret military contracts. The program had a benign public face and a classified body of secrets and lies. , Adolf Hitler told his inner circle at a dinner party in 1942, and in the aftermath of the German surrender more than sixteen hundred of Hitlers technologists would become Americas own. What follows puts a spotlight on twenty-one of these men.

Under Operation Paperclip, which began in May of 1945, the scientists who helped the Third Reich wage war continued their weapons-related work for the U.S. government, developing rockets, chemical and biological weapons, aviation and space medicine (for enhancing military pilot and astronaut performance), and many other armaments at a feverish and paranoid pace that came to define the Cold War. The age of weapons of mass destruction had begun, and with it came the treacherous concept of brinkmanshipthe art , but because it was counter to democratic ideals. The men profiled in this book were not nominal Nazis. Eight of the twenty-oneOtto Ambros, Theodor Benzinger, Kurt Blome, Walter Dornberger, Siegfried Knemeyer, Walter Schreiber, Walter Schieber, and Wernher von Brauneach at some point worked side by side with Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, or Hermann Gring during the war. Fifteen of the twenty-one were dedicated members of the Nazi Party; ten of them also joined the ultra-violent, ultra-nationalistic Nazi Party paramilitary squads, the SA (Sturmabteilung, or Storm Troopers) and the SS (Schutzstaffel, or Protection Squadron); two wore the Golden Party Badge, indicating favor bestowed by the Fhrer; one was given an award of one million reichsmarks for scientific achievement.

Six of the twenty-one stood trial at Nuremberg, a seventh was released without trial under mysterious circumstances, and an eighth stood trial in Dachau for regional war crimes. One was convicted of mass murder and slavery, served some time in prison, was granted clemency, and then was hired by the U.S. Department of Energy. They came to America at the behest of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Some officials believed that by endorsing the Paperclip program they were accepting the lesser of two evilsthat if America didnt recruit these scientists, the Soviet Communists surely would. Other generals and colonels respected and admired these men and said so.

To comprehend the impact of Operation Paperclip on American national security during the early days of the Cold War, and the legacy of war-fighting technology it has left behind, it is important first to understand that the program was governed out of an office in the elite E ring of the Pentagon. The Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) was created solely and specifically to recruit and hire Nazi scientists and put them on weapons projects of the Third Reich.

Operation Paperclip left behind a legacy of ballistic missiles, cluster bombs, underground bunkers, space capsules, and weaponized bubonic plague. It also left behind a trail of once-secret documents that I accessed to report this book, including postwar interrogation reports, army intelligence security dossiers, Nazi Party paperwork, Allied intelligence armaments reports, declassified JIOA memos, Nuremberg trial testimony, oral histories, a generals desk diaries, and a Nuremberg war crimes investigators journal. Coupled with exclusive interviews and correspondence with children and grandchildren of these Nazi scientists, five of whom shared with me the personal papers and unpublished writings of their family members, what follows is the unsettling story of Operation Paperclip.

All of the men profiled in this book are now dead. Enterprising achievers as they were, just as the majority of them won top military and science awards when they served the Third Reich, so it went that many of them won top U.S. military and civilian awards serving the United States. One had a U.S. government building named after him, and, as of 2013, two continue to have prestigious national science prizes given annually in their names. One invented the ear thermometer. Others helped man get to the moon.

How did this happen, and what does this mean now? Does accomplishment cancel out past crimes? These are among the central questions in this dark and complicated tale. It is a story populated with Machiavellian connivers and men who dedicate their lives to designing weapons for the coming war. It is also a story about victory, and what victory can often entail. It is rife with Nazis, many of whom were guilty of accessory to murder but were never charged, and lived out their lives in prosperity in the United States. In the instances where a kind of justice is delivered, it rings of half-measure.

Or perhaps there is a hero in the record of fact, which continues to be filled in.

Only the dead have seen the end of war.