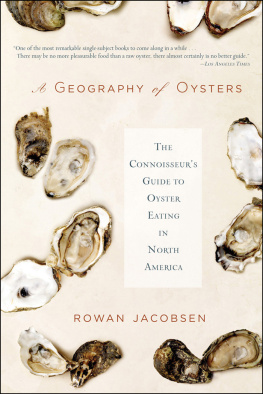

A GEOGRAPHY OF OYSTERS

The ConnoisseursGuide

toOysterEating

inNorthAmerica

ROWAN JACOBSEN

CONTENTS

This book is designed to make you a more savvy and satisfied eater of oysters. Its divided into three parts. The first, Mastering Oysters, gives you context. While its possible to know nothing about oysters and still enjoy them, your experience will be greatly enriched by background knowledge. Its like attending a painting exhibition. Instinctive reactions are important, but most people get more out of an exhibit by reading the accompanying texts and understanding something about the artist, the materials, the movement, and the vocabulary others use to discuss it. Think of an oyster as a minor work of art; knowing something about where it came from, how it came to be, and how it might be described will give meaning to your meal.

The second part, The Oyster Appellations of North America, provides a guide to the 132 most commonly encountered oysters. It explains the natural and human factors that influence the flavor and appearance of oysters from each area. Rather than reading it straight through, you can use it, along with the Oyster Index at the back of the book, to learn about any oyster you come across in a restaurant or seafood shop. Once you have a few oysters under your belt and are starting to identify the geography of your favorites, use this section to seek out other oysters that have similar provenance, or, better still, to plan your own oyster crawl in that area.

The third part, Everything You Wanted to Know About Oysters but Were Afraid to Ask, helps you put your newfound oyster expertise into practice. Its where youll find information on shucking oysters, serving them, cooking them, pairing them with wines, and so on. It highlights the best oyster bars and festivals, as well as growers who will pull their oysters straight out of the sea and mail them to your door. It also includes information on safety and nutrition, so you can eat oysters worry-freeand help others to do the same.

I was twelve years old when I discovered that raw oysters were the best food on earth and not, as I had assumed, the most disgusting. After a day spent bodysurfing the big breakers out beyond the sandbar at New Smyrna Beach, Florida, my family ducked, sunburned and salt-encrusted, into Stormysa real bar. While my mother sidled away toward the safety of some mozzarella sticks, and my younger brothers stared at me with Youre going to put what in your mouth? faces, I climbed onto a barstool next to my father, lifted to my mouth an oyster on the half-shell, slurped it in, gave a few halfhearted chews, and left childhood behind.

I matched my dad, oyster for oyster, through a couple of dozen that day. The first had been a dare, no question, and the second was to prove that the first wasnt a fluke, but I ate the third because there was something vital about the experience that I didnt quite understand but wanted to experience again, and I ate the fourth one because I couldnt stop.

Dad and I killed a lot of oysters back then. They were a dime apiece during happy hour at Stormys. They werent even especially good oysters, I know nowlikely bought on the cheap from some fetid Gulf Coast backwaterbut they were my initiation into another way of eating. In an America where we rarely ate recognizable creatures, oysters were the real deal, unadorned and live. This food didnt come to you prepped, cooked, and otherwise altered to make it as pleasing and unthreatening as possible. You had to leave your familiar surroundings, cross the cultural bridge, and risk the wild world.

Then there was the taste. Oysters taste like the sea. This fundamental truth has been pointed out enough times that it is easy to forget how extraordinary it is. Oysters taste like the sea. No other food does. Not lobsters, not saltwater fish, not scallops or clams or even kelp. Beef tastes meaty, milk tastes creamy, but the comparison for oysters is not a taste or another food but always a place. And a placethe seacoast for which many of us have romantic associations. From oysters I learned that whats important about good food is not just what it gives you, but where it can take you.

The next step in my oyster odyssey was easy. South of New Smyrna Beach is Canaveral National Seashore, 220 square miles of wilderness surrounding the Kennedy Space Center. The Atlantic flows through Ponce Inlet and into Mosquito Lagoon, an immense estuary protected by Canaverals mass. I used to canoe there a lot, amid miles of flat green water and egrets and palm trees and marshand the occasional column of fire from a NASA launch. And it was there that I noticed the rocks sticking just above the water surface at low tide. Florida has no rocksits sand, sand, sandso these were worth investigating. They were beds of oysters, piled on top of each other, revealed at low tide and hidden again at high. I might as well have come across Spanish doubloons.

Soon I was bringing hammers and a plastic bucket, and returning in my canoe with more oysters than I could eat. Some I would whack off with a hammer and open on the spot, returning the empty shells to the lagoon. This was a revelation. No raw bar required! Those oysters took me out of the suburbs and into a relationship unchanged since prehistory. Was I a Florida eighth-grader in an Ocean Pacific T-shirt or a Timucuan Indian boy cruising the coast? You couldnt have told from my meal.

When I think back on those oysters, Im first and foremost pleased that Im not dead. Those were risky oysters. Vibrio vulnificus, a parasite that infects oysters and is responsible for a few deaths a year, lives only in warm water. Stick to coldwater northern oysters and your risk is virtually nonexistent. Ill bet the water in my lagoon was 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

I didnt harvest another oyster myself for twenty-five years. That one was in Maine, about as far from my warm Florida oysters as I could get. On the frigid shore of the Damariscotta River, I pulled up a thick- shelled oyster, held it awkwardly against my thigh, pried it open with a knife, cut its adductor muscle, and dumped it into my mouth. The meat was cool, briny, and brimming with life. I felt full of well-being and deeply connected to the earthas well I should have. A mile up the river inlet, a two-thousand-year-old shell midden bore testament that humans had been connecting to the earth in just this spot, in just this way, for a long, long time.

My Damariscotta oyster belonged to the exact same species Eastern (Crassostrea virginica)as the Mosquito Lagoon oyster Id eaten a quarter-century earlier in Florida, but it couldnt have tasted more different. Where the Florida oyster tasted a bit muddy and soft, the Maine oyster was fresh, firm, and briny as all get-out. It tasted like, well, Maine. And it drove home a point that is central to this book: More than any other food, oysters taste like the place they come from. Oysters are creatures of bays and tidal pools and river inlets, of places where marine and terrestrial communities collide. While they are creatures of the sea, they draw their uniqueness from the land and how it affects their home waters. They have a somewhereness to them, like great wines, and in a mass-produced society where most foods dont seem to be from anywhere, this makes them special. You cant look at a grape and tell that its from northern Chile. You cant taste a supermarket rib-eye and say, Ah, yes, the grasslands ofWyoming. But with an oyster, you can sometimes pinpoint its home simply by looking at it. With a little practice, you can often tell by tasting it. Think of an oyster as a lens, its concave shell focusing everything that is unique about a particular body of water into a morsel of flesh. Thats why not only do Florida oysters and Maine oysters taste different, but oysters in one Maine bay taste different from oysters in the next.

Next page