Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

For my little pearl, Ava Maeve Walsh

ONE

The Texas Shell Game

GALVESTON BAY WAS CALM, the sky was blue, and the water temperature hovered at sixty degreesperfect oyster weather. I stood on the deck of the Trpanj, a typical Texas oyster lug. Wide across the middle with a huge foredeck, it looked like a barge with an upturned nose. The captain steered from a wheel set up front where he could see the dredge, a five-foot metal-rake-and-net contraption that he dragged across the bottom of the shallow bay.

With a belch of exhaust and a roar like a tractor trailer entering the highway, a powerful diesel motor spun a spool of cable that hauled up the dredge full of oysters and debris. The dredge swung on its chain, and two Mexican deckhands balanced it on a metal frame welded to the side of the deck before tipping its contents onto a worktable. The deckhands sorted the keepers out of the gray jumble. Then they shoved the empty shells and undersized oysters back overboard and dropped the dredge again.

The Trpanj is owned by oysterman Misho Ivic and named after his home village in Croatia. Mishos son Michael had agreed to take me out on the oyster boat and show me how the dredging business worked. I studied a map of the Galveston Bay oyster reefs from the bow. There are four categories in Galveston Bay, Michael explained, pointing to them on the map.

The prohibited reefs are close to shore. They are closed to oystering due to the wastewater runoff they get from suburban lawns, cow pastures, and other possible sources of contamination. Conditional areas are open to fishing most of the time, but the game wardens rule them off-limits after heavy rains because of the runoff. Open oyster reefs are the public reefs that are open throughout the season. And leased areas are private oyster reefs.

Michael grabbed a dripping oyster from the pile of keepers on the deck, pried off the top shell and handed it to me. Shocked by its sudden exposure to the air, the oysters delicate lips contracted almost imperceptibly. I tilted it back and slurped the wet flesh into my mouth, chewing slowly. The flavor was salty, a little metallic, and surprisingly sweet.

Eating raw oysters is at once perverse and spiritual. A freshly shucked oyster enters your mouth while it is still alive and dies while giving you pleasure. As I savored the wonderfully slick texture, delicate briny flavor, and marine aroma, it was easy to see how oysters came to be associated with the tenderest portion of the female anatomy.

But since oysters from the waters of Galveston Bay carry a common bacteria that kills a few people every year, I also found myself contemplating my mortality as I swallowed. Its quite an exciting thing to put in your mouth, a meek and vulnerable living being brimming with bold seafood flavors, vivid sexual fantasiesand the threat of death.

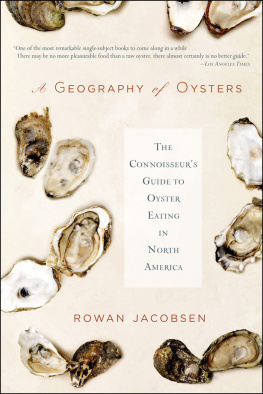

For the last twenty years, oysters have been making a comeback on the American food scene. And as a food writer living in one of the nations largest oyster-producing states, I was keen on learning more about them. With my camera and notebook constantly in hand, I asked a lot of questions.

Galveston Bay, Texas

Ivic and the oystermen on the Trpanj regarded me as an earnest idiot. As would the oystermen I interviewed in New York, California, Washington State, England, France, and the rest of the oyster-producing world.

The tried-and-true formula for writing about oysters is to go find colorful oystermen and copy down their stories. You go out on a boat or visit an oyster farm and eat some quivering mollusks on the spot, rave about your intense perception of terroir (or merroir, as the marine version of this poetic sense of place is sometimes known). And then you quote the oysterman on the important facts to know about oysters.

I attempted to employ this formula myself. But it didnt work out. In the five years its taken me to write this book, I asked too many questions. I never lost my passion for oysters. But I did lose my innocence. I learned that terroir, or merroir, or whatever you call it, is a very flexible conceptand that most of what oystermen have to say about oysters is malarkey.

I was eager and clueless when I climbed aboard the Trpanj in December of 2003 to write my first article about oysters for the Houston Press, a weekly owned by the Village Voice chain. I called my feature Sex, Death & Oysters, just the sort of racy title an alternative weekly editor loves. I wrote about the oysters reputation as an aphrodisiac, and did a little investigative work on why tainted Texas oysters seemed to be killing people. It was mainly a good excuse to go for a ride on an oyster boat and eat a lot of oysters.

I thought pollution would be a good angle. The waters of Galveston Bay that I could see were a frightening shade of mud brown. To our southwest, a line of rusty oil tankers were steaming in from the Gulf of Mexico, proceeding north through the Bay and up the shipping lane toward the Houston Ship Channel. Lots of toxins are found in the sediment out in the Gulf of Mexico. Surely there were some environmental hazards to expose in Galveston Bay.

But I never did find any. The murkiness, or turbidity, as scientists call it, came from suspended sediments and plankton. The Adriatic is beautiful blue, Croatian-born Misho Ivic told me, but theres nothing living in it. Its sterile. Galveston Bay looks muddy because the water is full of food. Good for the oysters, good for the crabs.

I didnt trust him, of course. East Coast and West Coast oystermen say that the waters of the Gulf of Mexico are filthy. And maybe they are. But oysters live in brackish water in freshwater estuaries, not in the Gulf of Mexico. And the scientists I interviewed said that Galveston Bay was in pretty good shape.

We always fight the perception that the bay is polluted, but the reality is that the water quality overall is good, Scott Jones, water and sediment quality coordinator for the Galveston Bay Estuary Program, told me. He said dissolved oxygen levels have gone up markedly in the last thirty years thanks to a cleanup of wastewater treatment plants mandated by the Clean Water Act of 1972.

Misho Ivic and a marine biologist named Dr. Sammy Ray put pollution into a historical perspective for me by comparing Galveston Bay to Chesapeake Bay. Chesapeake Bay produced millions of bushels of oysters in the 1800s, before it was polluted. It now produces about 1 percent of its historic peak. Conservationists in Maryland and Virginia are making progress and the oyster harvests are increasing, but since the surrounding wetlands were long ago destroyed, the long-term prospects are limited.

In 1900, Galveston Bay and a couple of other small bays in Texas produced a record 3.5 million pounds of oyster meat. But modern harvests regularly exceed that. In 2003, the largest harvest of oysters ever recorded was taken6.8 million pounds, nearly double what was produced at the turn of the century.