Eichmann in My Hands

Peter Z. Malkin and Harry Stein

For Fruma

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many hands and hearts went into the making of this book.

For their perseverance and unflagging support, we thank Roni, Priscilla, Omer, Tamar, and Adi.

For the special quality of their friendship we thank Saul and Robert Steinberg. For their generosity and understanding we thank Uri Dan, Steve and Marina Kaufman, and Professor Wolf Kirsh and Marie Kirsh.

Howard and Judith Steinberg were never not there.

Larry Kirshbaum and Jay Acton believed in this project from the start. Jamie Raab and Ellen Herrick were free with their time and counsel. Susan Suffes was an extraordinarily thoughtful and sensitive editorial voice.

Joshua Morgenthau, Sadie and Charlie Stein, and Adam Zion served as a particular source of inspiration; living evidence that, for all the horrors of the past, there is a future in which to believe.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The Holocaust occurred a mere fifty years ago; tens of millions remember it firsthand, and survivors still wander among us. Yet, to an almost uncanny degree, it has already begun to recede into history. For many of the young in particular, the unspeakable events of those years seem increasingly to carry little more emotional weight than the Boer War or the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Even for many alive at the time, names and places intimately bound up with the Nazi program of genocide have grown indistinct, familiar yet stripped of specific meaning. Names like Heydrich and Streicher. Places like Babi Yar, Sobibor, the ghettoes of Lodz and Vilna and Warsaw.

In one important sense Adolf Eichmann stands as an exception to that rule. Thirty years after his execution his name still rings notorious; he was the number-one war criminal hunted down in the postwar era. Yet tellingly, the lessons of even the Eichmann case have grown hazy, the general impression somehow being that the notorious SS Obersturmfhrer was merely an important cog in a vast and impersonal machine, and, more, that Nazism itself was an aberration, and we will never see its like again.

We understand as well as anyone why the full import of Eichmann as a moral example so often fails to register. By the measures usually applied to such things, he was not an obviously cruel or thoughtless man. Were he living among us today and, say, running a shoe factory, he would probably be regarded with quiet respect; a steady husband and father, producing excellent shoes at a fair price, a pride to his community.

Yet this is precisely what ought to make the Eichmann story continually unsettling, and never more so than in times as ethically ambiguous as our own. For it is not just about the unspeakable evil perpetrated by the agents of Nazismwhere we are comfortably able to identify with the victimsbut about the astonishing capacity of those not wholly unlike ourselves for self-justification; the ease with which, in the interest of ideology or simple ambition, seemingly normal souls escape their better selves.

History has appropriately branded Adolf Eichmann a monster, a man oblivious to every impulsecompassion, remorse, respect for the sanctity of lifeby which we ought to define our humanity. Still, if we look closely, the most shocking thing is that he seems so very familiar.

Peter Z. Malkin and Harry Stein

INTRODUCTION

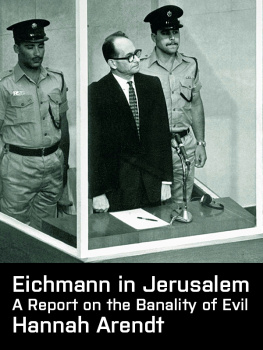

A little past midday on a sweltering day in July 1961, I joined a long line snaking around a large, low building in central Jerusalem. Formerly a community center known as the Beit Hamm (the House of the People), it had lately been converted into a courtroom, one vast enough to accommodate 750 spectators, including reporters from forty countries, an elevated bank of TV and newsreel cameras, and, where ordinarily the defendant would sit, a spacious booth of bulletproof glass.

The booth was widely recognized as a major innovation in personal security, but already it had also come to stand for something else: the isolation of Adolf Eichmann from the rest of humanity.

As I waited, I made note of the security outside the building as well. A ten-foot fence of steel mesh had been erected around the entire structure. Border policemen patrolled its roof and grounds, submachine guns at the ready. Even now, at lunch hour, the building was bathed in floodlights, making the temperature almost unbearable.

Within twenty minutes my shirt was soaked through; within forty-five my head was starting to pound. Up and down the line, people were complaining: What was going on here; when were they going to open the doors? Even the group of Yemeni schoolchildren, brought here by their teacher to witness history in the making, had grown listless.

The heat did little for my disposition. History was the furthest thing from my mind; I had come only reluctantly, to honor a commitment. Now, as the minutes passed in that blast-furnace heat, I was more persuaded than ever that the errand was pointless. More than a year had passed. Surely Eichmann himself no longer remembered that exchange back in Buenos Aires.

Nor were my spirits much raised when the line at last began edging forward and I found myself obliged to enter a cubicle in the building lobby and submit to a rigorous body search: a reminder, as if any were needed, that even on my native soil I was without identity or standing, the very nature of my work a state secret. Hell, if Id wanted to KILL the sonofabitch, Id have done it then!

All of which has a lot to do with why, another twenty minutes later, I was so surprised by my own excitement as an urgent murmur passed over the crowd. I strained forward in my seat, above the judges bench and a little to the left. There he was, being led into his booth.

The sight was staggering. Though doctors had dismissed his lawyers claim that he had suffered two heart attacks in the three months since the start of the trial (the condition was diagnosed as functional arrhythmia), neither they nor the photos had suggested the extent of the mans physical deterioration. Fifteen pounds lighter than when I had last seen him, his cheeks deep shadows and the blue suit made for him by an Israeli tailor limp on a narrow frame, his skin had gone a waxy yellow. Seeing him, it was easy to believe, as Eichmanns associate counsel had recently claimed, that the fifty-five-year-old defendant had become obsessed with a prediction made years before by an Argentine gypsy that he would not live past his fifty-seventh birthday.

And yet he didnt carry himself like a beaten man. Taking a seat at the desk within his cage, oblivious to the blue-uniformed policemen on either side (like all of Eichmanns guards, of non -European origin), he immediately began organizing his papers into neat piles before him. As one observer had it, he was turning the glass booth into a tiny island of fussy bureaucracy.

And, moments later, when he began to speak, I knew for certain he had not changed. Instantly it all came back with full force: the mans astonishing self-control, his sense of certainty, his maddening, almost unbelievable, moral obtuseness.

Eichmann was in the midst of his eighth day of cross-examination, and the subject before the court, carried over from the morning session, was responsibility for the eradication of a group of one hundred Jewish children. From Lidice, the Czech village obliterated in 1942 in reprisal for the assassination by partisans of Eichmanns immediate SS superior Reinhard Heydrich, the children were dispatched en masse to the gas chambers at Chelmo.