CONTENTS

To Justice Served

N.B.

EICHMANN FAMILY

Adolf Eichmann , Nazi commander in charge of transportation for the Final Solution

Vera Eichmann , his wife

Nikolas (Klaus, Nick), Horst , Dieter , and Ricardo Eichmann , his sons

AUSCHWITZ SURVIVOR

Zeev Sapir

NAZI HUNTERS

Fritz Bauer , District Attorney of the West German state of Hesse

Manus Diamant

Lothar Hermann

Sylvia Hermann

Simon Wiesenthal

ISRAELI DEFENSE FORCES

Zvi Aharoni , chief interrogator for the Shin Bet, the Israeli internal security service

Shalom Dani , forgery expert

Rafi Eitan , Shin Bet Chief of Operations

Yonah Elian , civilian doctor

Yaakov Gat , agent for the Mossad, the Israeli secret intelligence network

Yoel Goren , Mossad agent

Isser Harel , head of the Mossad

Ephraim Hofstetter , head of criminal investigations at the Tel Aviv police

Ephraim Ilani , Mossad agent, based out of the Israeli embassy in Argentina

Peter Malkin , Shin Bet agent

Yaakov Medad , Mossad agent

Avraham Shalom , Deputy Head of Operations for Shin Bet

Moshe Tabor , Mossad agent

EL AL PERSONNEL - AIRLINE MANAGEMENT

Yosef Klein , Manager of El Als base at Idlewild Airport in New York City

Adi Peleg , Head of Security

Yehuda Shimoni , Manager

Baruch Tirosh , Head of Crew Assignments

EL AL PERSONNEL - FLIGHT CREW

Shimon Blanc , engineer

Gady Hassin , navigator

Oved Kabiri , engineer

Azriel Ronen , copilot

Shaul Shaul , navigator

Zvi Tohar , captain

Shmuel Wedeles , copilot

OTHER ISRAELIS

David Ben-Gurion , first Prime Minister of Israel

Haim Cohen , Attorney General of Israel

Gideon Hausner , Second Attorney General of Israel

Justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.

Lord Chief Justice Gordon Hewart, 1924

I sat at my desk and did my work. It was my job to catch our Jewish enemies like fish in a net and transport them to their final destination.

Adolf Eichmann

We will bring Adolf Eichmann to Jerusalem, and perhaps the world will be reminded of its responsibilities.

Isser Harel

A remote stretch of unlit road on a windy night. Two cars appear out of the darkness. One of them, a Chevrolet, slows to a halt, and its headlights blink off. The Buick drives some distance farther, then turns onto Garibaldi Street, where it too stops and its lights turn off. Two men climb out of the back of the Buick and walk to the front of the car, where one lifts the hood. Their breath steams in the cold air. One leans his burly frame over the engine. Another man gets out of the front passenger seat and climbs into the back, shutting the door after him. His forehead presses against the cold glass; his eyes fix on the highway and the bus stop.

In five minutes, the bus will arrive. There is no reason for any of the men to speak. They have only to wait and to watch.

A train roars across the bridge that spans the highway.

A young man wearing a bright red jacket, about fifteen years old, pedals down Garibaldi Street on his bicycle. He notices the Buick and stops to ask if they need any help. Its a remote neighborhood with few houses, after all. The driver steps halfway out of the car and, smiling at the youth, says in Spanish, Thank you! No need! You can carry on your way.

The men standing outside the car smile and wave at the youth too but stay silent. He takes off, his unzipped jacket flapping around him in the wind. There is a storm on the way.

Suddenly, headlights split the darkness. The green and yellow municipal bus emerges, but instead of stopping at exactly 7:44 P.M. , as it has done every other night the men have kept watch, it keeps going. It rattles past the Chevrolet, underneath the railway bridge, and then it is gone.

The man in the back of the Buick limousine speaks briefly. We stay, he insists. Nobody argues.

At 8:05, they see a faint halo of light in the distance. Another buss headlights shine brightly down the highway. This one slows and stops. Brakes screech, the door clatters open, and two passengers step out. As the bus pulls away, one of them, a woman, turns to the left, while the other, a man, heads for Garibaldi Street. He bends forward into the wind, his hands stuffed in his coat pockets.

He has no idea what is waiting for him.

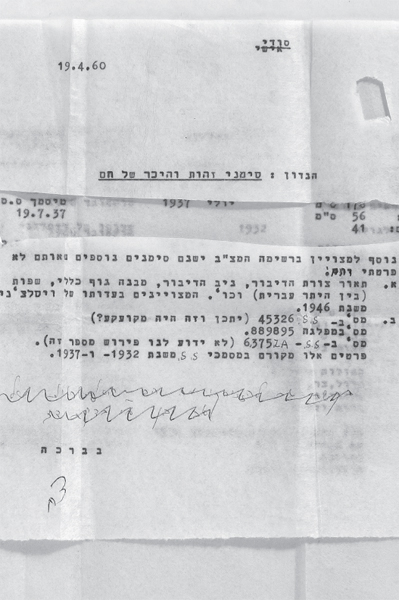

Adolf Eichmann in uniform during World War II.

Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann stood at the head of the convoy of 140 military vehicles. It was noon on Sunday, March 19, 1944, his thirty-eighth birthday. He held his trim frame stiff, leaning slightly forward as he watched his men prepare to move out.

The engines rumbled to life, and black exhaust spewed across the road. Eichmann climbed into his Mercedes staff car and signaled for the motorcycle troops to lead the way.

More than five hundred members of the Schutzstaffel, the Nazi security service better known as the SS were in the convoy, leaving Mauthausen, a concentration camp in Austria, for Budapest, Hungary. Their mission was to comb Hungary from east to west and find all of the countrys 750,000 Jews. Anyone who was physically fit was to be delivered to the labor camps for destruction through work; anyone who was not was to be immediately killed.

Eichmann had planned it all carefully. He had been in charge of Jewish affairs for the Nazis for eight years and was now chief of Department IVB, responsible for executing Hitlers policy to wipe out the Jews. He ran his office like it was a business, setting clear, ambitious targets, recruiting efficient staff members and delegating to them, and traveling frequently to monitor their progress. He measured his success not in battles won but in schedules met, quotas filled, and units moved. In Austria, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Slovakia, Romania, and Poland, Eichmann had perfected his methods. Now it was Hungarys turn.

Stage one was to isolate the Jews. They would be ordered to wear Yellow Star emblems on their clothes, forbidden to travel or to use phones and radios, and banned from scores of professions. He would remove them from Hungarian society.

Stage two would secure Jewish wealth for the Third Reich. Factories and businesses would be taken over, bank accounts would be frozen, and the assets of every single individual would be seized, down to their ration cards.

Stage three: the ghettos. Jews would be uprooted from their homes and sent to live in concentrated, miserable neighborhoods until the fourth and final stage could be effected: the camps. As soon as the Jews arrived at those, another SS department would be responsible for their fate. They would no longer be Adolf Eichmanns concern. That was how he saw it.

Next page