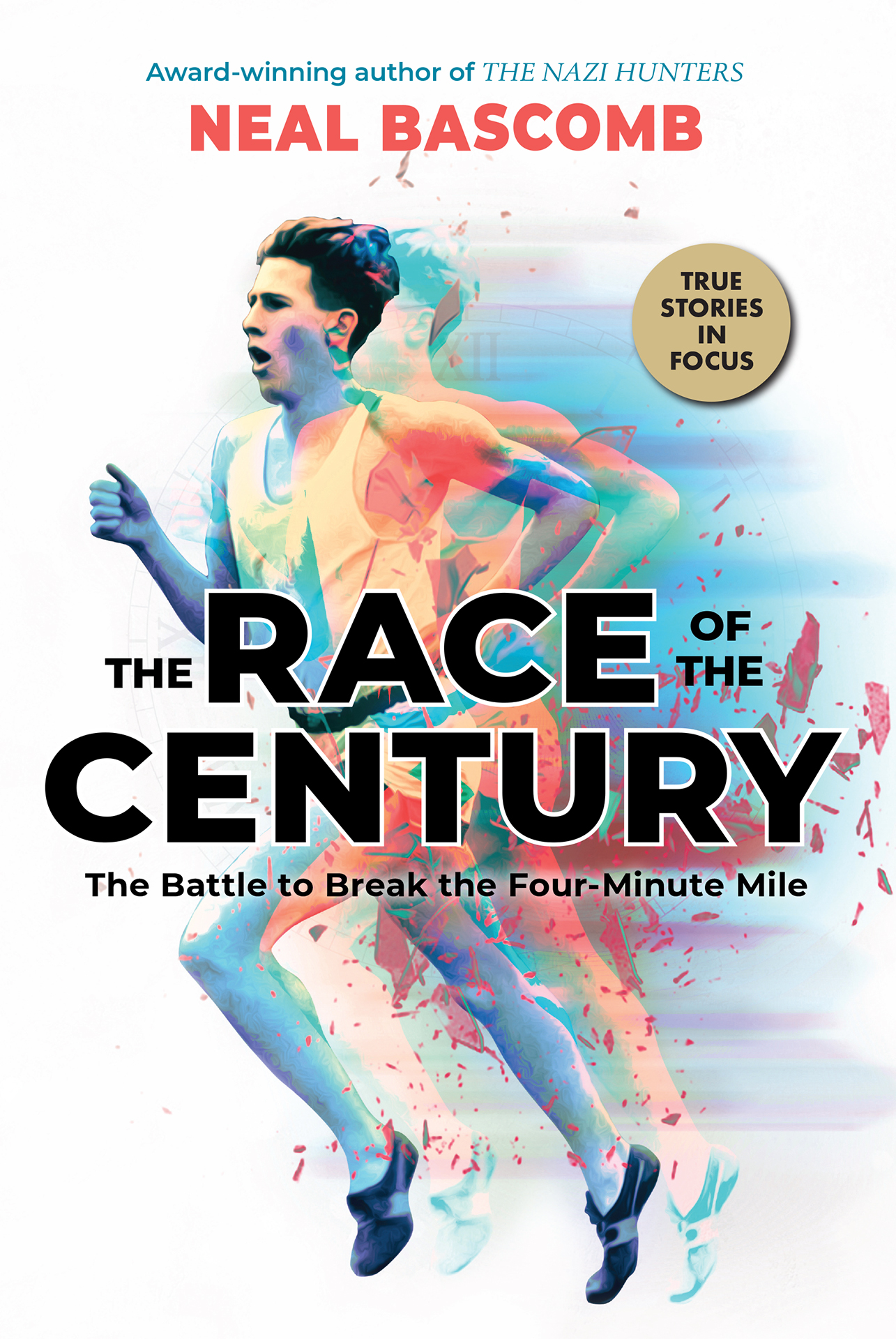

S EVENTY YEARS AGO, most people considered running four laps of the track in four minutes to be beyond the limits of human speed, foolhardy, and possibly dangerous. A Frenchman asked of the first runner who broke the four-minute mile, How did he know he would not die?

But the barrierphysical and psychologicalbegged to be broken. The figure seemed so perfectly round, one writer explained: four laps, four quarter miles, four-point-oh-oh minutesthat it seemed God himself had established it as mans limit. For decades the best middle-distance runners tried and failed. They came within two seconds, but that was as close as they were able to get. Attempt after spirited attempt failed.

Running the mile was considered an art form in itself, requiring a balance of speed and stamina. The person to break the four-minute barrier would have to be fast, highly trained, and so supremely aware of his body that he would cross the finish line just at the point of complete exhaustion.

In August 1952, three young men set out to be first to break the barrier. Wes Santee was a natural athlete, born to run fast. The son of a Kansas ranch hand, he amazed crowds with his talent and basked in the publicity. Then there was John Landy, the Australian who trained harder than anyone else and had the weight of a nations expectations on his shoulders. Running revealed to Landy a discipline he never knew he had. Finally, there was Roger Bannister, the English medical student for whom the sub-four-minute mile was a challenge of the human spirit, to which he brought a scientific plan and a magnificent finishing kick.

All three spent a large part of their early twenties struggling for breath and training week after week to the point of collapse. Money was not a factorthey were all amateurs, and the prize for winning a race was usually a token: a watch or a small trophy. The reward was in the effort, in winning, in being the best.

One of the three finally breasted the tape in 3:59.4, but the contest did not end there. The barrier was broken, but the question remained: Whowhen they toed the starting line togetherwould come out on top and run the perfect mile?

O NLY A SCATTERING of people were there to watch the two men in singlets and shorts tear down the straight of the track at Motspur Park athletics stadium. The sole reason Ronnie Williams hadnt folded was because, in his role as pacesetter, all he had to do was set the speed of the time trial that the other runner, Roger Bannister, wanted to hit and maintain it for a lap and a half. Another pacesetter, Chris Chataway, had covered the first half of the three-lap trial. Motspur Park, in South London, was one of the fastest tracks in England, which was why Bannister had chosen it. The surface was typical for the time: a dirt oval topped with a layer of ash cinders recycled from coal-fired electricity plants.

It would be inadequate to describe what Bannister was doing as simply running. He was eating up the track at a pace of seven yards a second. Journalist Terry OConnor described his style: Bannister had terrific grace, a terrific long stride, he seemed to ooze power. It was as if the Greeks had come back and brought him to show you what the true Olympic runner was like. Bannister was tallsix foot oneand long-limbed, with a chest like an engine block and arms that moved like pistons. So balanced and even was his foot placement that some people said he could have walked a tightrope as easily as a track. There was no jarring shift of gears when he accelerated, as he did now, at the end of the three-quarter-mile time trial, only an even increase in tempo. He loved that moment of acceleration at the end of a race when he drew upon the strength of leg, lung, and will to surge ahead.

Bannister shot across the finish, and timekeeper Norris McWhirter punched down the button on his stopwatch. On reading the time, he gasped. Norris and his twin brother, Ross, had been friends with Bannister since their days at Oxford University. Norris had always known there was something special about Bannister, but as he stared down at his stopwatch that July afternoon, he could hardly believe the time: three-quarters of a mile in 2 minutes and 52.9 secondsfour seconds faster than the world record held by the great Swedish miler Arne Andersson.

After catching his breath, Bannister walked over to see what the stopwatch read. Cinders clung to his running spikes. In those days athletic shoes were made of thin leather molded so snugly to the feet that when the laces were drawn tight, you could see the ridges of the toes. The soles were embedded with six or more half-inch steel spikes, for traction.

Two fifty-two-nine, Norris said.

Bannister was taken aback. The time had to be wrong. You could have brought a watch we could rely on, he said.

He always ran a three-quarter-mile time trial before a big race to gauge his fitness level and judgment of pace. This one was particularly important because in ten days time, provided he qualified in the heats, he would be running in the 1,500-meter final at the Helsinki Olympics, a race he had dedicated the past two years to winning. A good time this afternoon would be crucial for his confidence.

Norris was cross at the suggestion that his watch was unreliable and dashed to a telephone booth near the concrete stadium stands. He put a penny in the slot and dialed, and a toneless voice came on the line: On the third stroke, the time will be 2:32 and 10 secondsbipbipbip. On the third stroke, the time will be 2:32 and 20 secondsbipbipbip. The stopwatch was accurate.

Bannister always considered that being able to run three-quarters of a mile in three minutes meant he was in top racing shape. He was now seven seconds under that benchmark. All his training for the past two years had been focused on reaching his peak at exactly this moment, and he was certain of a very good show at the Helsinki Games.

However, there was a complication Bannister did not yet know about. As a sports journalist, Norris McWhirter kept his ear to the ground, and he had heard that a semifinal had been added to the 1,500-meter contest because of the higher-than-expected number of entrants. Bannister would have to run not just a qualifying heat but also a semifinal before reaching the final.

The four men bundled into Norriss black car and headed back to Central London. As they turned out of the park, Norris finally said, Roger they put in a semifinal. They all knew what he meant: three races in three days.

Bannister looked out the window, saying nothing. He had trained for two races. Adding another would require a significantly higher level of stamina.

The closer they got to London, the more they could see of the wars destructionbombed-out buildings that had yet to be bulldozed and rebuilt. When World War II finished in 1945, the British people discovered that while they had survived, they had grim days ahead. Britain owed 3 billion, principally to the United States. Exports had dried upin large part because half the countrys merchant fleet had been sunk. Returning soldiers found rubble where their homes had once stood. There were lines for the most basic staples, and ration books were requiredeven for childrens sweets.