N.B.

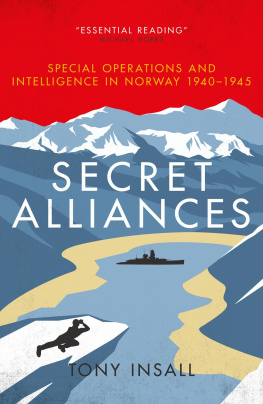

OPERATION GROUSE

Einar Skinnarland

Jens-Anton Poulsson , leader of Grouse

Claus Helberg

Knut Haugland , radio operator

Arne Kjelstrup

OPERATION GUNNERSIDE

Joachim Rnneberg , leader of Gunnerside

Knut Haukelid

Birger Strmsheim

Fredrik Kayser

Kasper Idland

Hans Storhaug

D/F HYDRO SINKING

Rolf Srlie , construction engineer at Vemork

Knut Lier-Hansen , Milorg resistance fighter

Alf Larsen , engineer at Vemork

Gunnar Syverstad , laboratory assistant at Vemork

Kjell Nielsen , transport manager at Vemork

Ditlev Diseth , Norsk Hydro pensioner

NORWEGIANS

Leif Tronstad , scientist and Kompani Linge leader

Haakon VII , king of Norway

Jomar Brun , chief engineer at Vemork

Odd Starheim , member of the resistance

Oscar Torp , defense minister

Torstein Skinnarland , brother of Einar

Olav Skogen , leader of local Rjukan Milorg

ALLIES

Winston Churchill , prime minister of Great Britain

Franklin D. Roosevelt , president of the United States

Eric Welsh , head of the Norwegian branch of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS)

Colin Gubbins , major general who served as second-in-command of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE)

John Wilson , chief of the Norwegian section of the SOE

Wallace Akers , head of the British Directorate of Tube Alloys

Mark Henniker , British lieutenant colonel in charge of Operation Freshman

Owen Roane , American Air Force pilot

NAZIS IN NORWAY

Josef Terboven , Reichskommissar in Norway

General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst , head of German military forces in Norway

SS Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich Fehlis , head of the Gestapo and security forces in Norway

GERMAN SCIENTISTS

Kurt Diebner

Werner Heisenberg

Otto Hahn

Walther Gerlach

Paul Harteck

Abraham Esau

The is pronounced uh, like the u in burn. Rnneberg would thus be pronounced Runneberg.

The is pronounced oh, in short or long forms. Mna would thus be pronounced Mona.

The is pronounced ah, like the a in cat (short form) or in bad (long form). Ml would thus be pronounced Mahle.

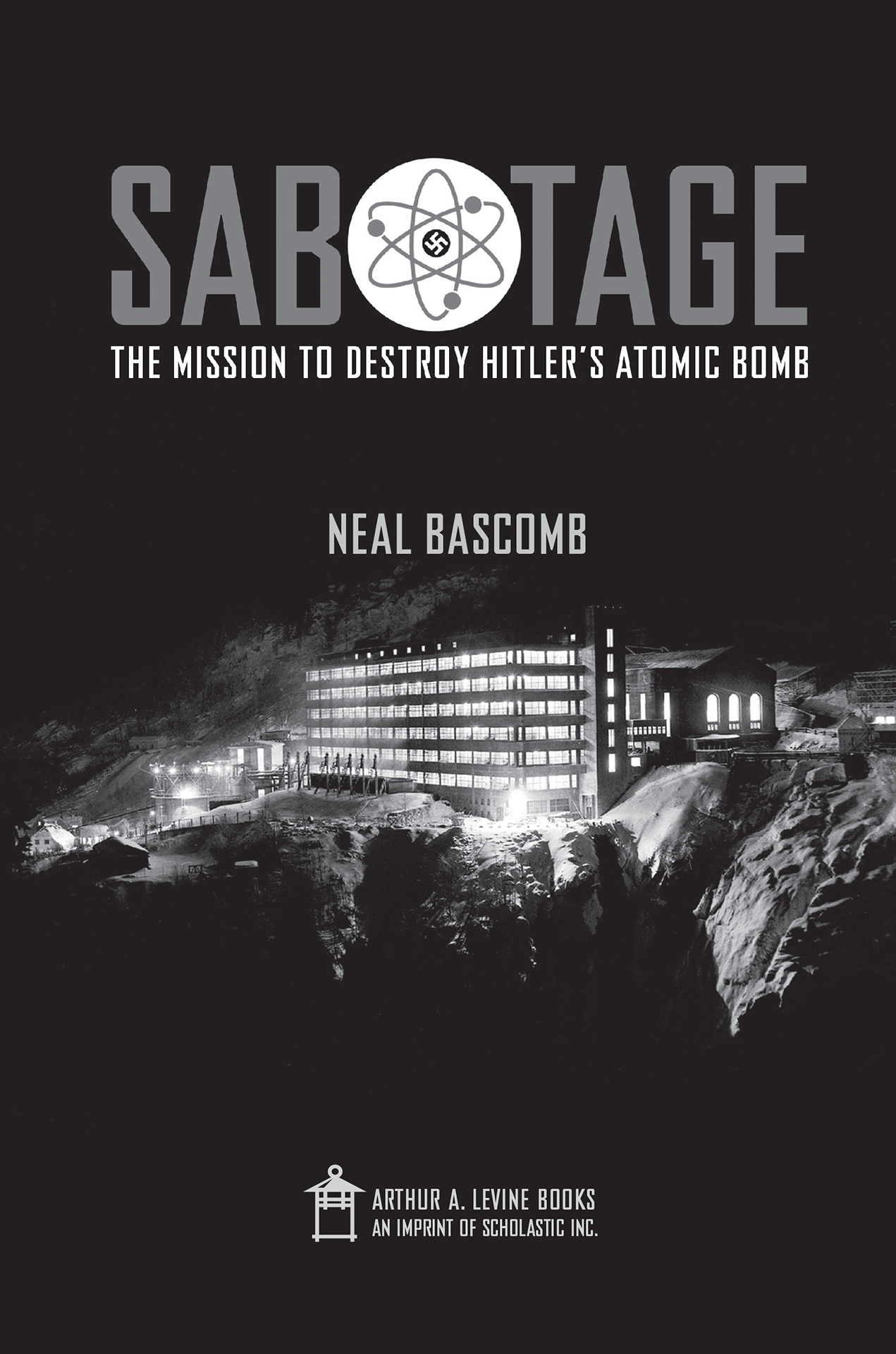

Nazi-occupied Norway, February 27, 1943

In a staggered line, they cut across the mountain on their skis. Dressed in white camouflage suits over British Army uniforms, the young men threaded through the stands of pine and moved down the sharp, uneven ground. The silence was broken only by the swoosh of skis and the occasional slap of a pole against a branch. The warm, steady wind that blew through Vestfjord Valley dampened even these sounds. This was the same wind that would eventually, hopefully, blow their tracks away.

A mile into their trek, the woods became too dense and steep to descend by any means other than by foot. The nine Norwegian commandos took off their skis and balanced them on their shoulders. Then they slid and trudged down through the wet and heavy snow. They carried thirty-five-pound backpacks filled with survival gear, submachine guns, grenades, pistols, explosives, and knives. Each one also had a cyanide pill in case of capture by the enemy. Often the weight of their equipment made them sink to their waists in the snow.

Suddenly, the forest cleared, and they came upon the road. Ahead of them, on the other side of a terrifying gorge, stood Vemork, their target. The enormous power station, and the eight-story hydrogen plant in front of it, were built on a rocky shelf that extended over the gorge. Below it, the Mna River snaked through a valley so deep that the sun rarely reached its base. Despite the distance across the gorge, and the wind singing in their ears, the commandos could hear the stations low hum.

Before Hitler invaded Norway and the Germans seized control of the plant, Vemork would have been lit up like a beacon. But now its windows were blacked out to discourage nighttime raids from Allied bombers. High on the icy crag, its dark silhouette looked like a winter fortress. A single-lane suspension bridge provided the only point of entry for workers and vehicles, and it was closely guarded by the Nazis. Mines littered the surrounding hillsides. Patrols swept the grounds. Searchlights, sirens, machine-gun nests, and a barrack of troops were also at the ready.

And now the commandos were going to break into it.

The young men stood mesmerized. They had been told the plant produced something called heavy water, and with this mysterious substance, the Nazis would be able to blow up a good part of London. But none of the saboteurs were there for heavy water, or for London. They had seen their country invaded by the Germans, their friends killed and humiliated, their families starved, their rights curtailed. They were there for Norway, for the freedom of its lands and people from Nazi rule.

They refastened their skis and started down the road to their mission.

In the dark early hours of April 9, 1940, a fierce wind swept across the decks of the German cruiser Hipper and the four destroyers at its stern as they cut into the fjord toward Trondheim, Norway. The ships approached the three forts guarding the entrance to the city, all crews at the ready. A Norwegian patrol signaled for the boats to identify themselves. In English, the Hipper s captain returned that they were a British ship with orders to go towards Trondheim. No unfriendly intentions. As the patrol shone a spotlight across the water, it was blinded by searchlights from the Hipper , which suddenly sped up and blew smoke to hide its whereabouts.

Signals and warning rockets lit up the night. Inside the Norwegian forts, alarms rang and orders were given to fire on the invading ships. But the inexperienced Norwegian soldiers struggled to shoot their guns. By the time they were prepared, the Hipper was already steaming past the first fort. At the second fort, the bugler who should have sounded the alarm had fallen asleep at his post. The moment the gunners there opened fire, their searchlights malfunctioned, so they could not see their targets.