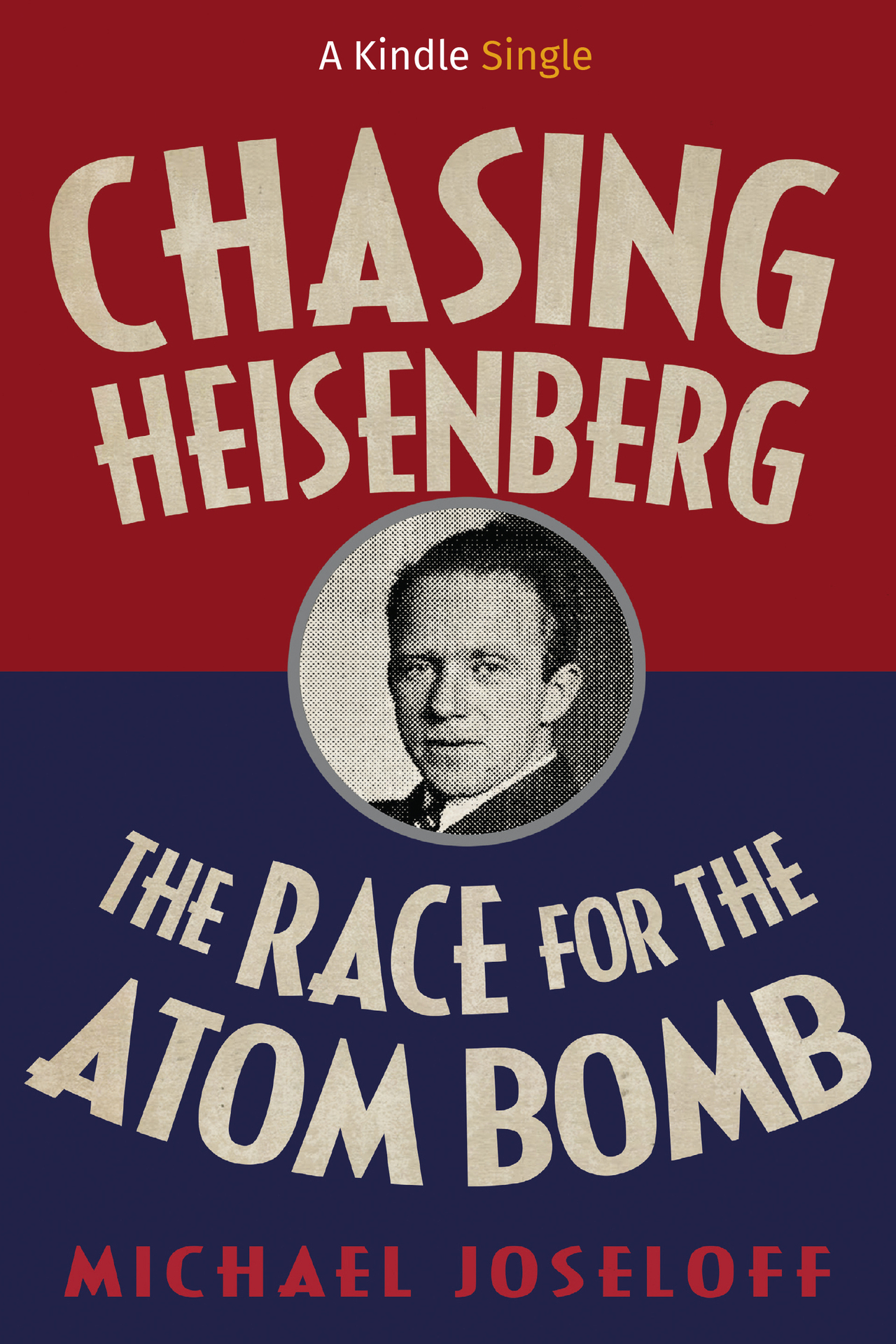

Text copyright 2018 by Michael Joseloff

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Amazon Publishing, Seattle

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Amazon Publishing are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc., or its affiliates.

eISBN: 9781503935556

Cover design by RBDA Studio

INTRODUCTION

I FOUND THE PHOTO while browsing the internet: five men dressed in jackets and ties, smiling and posing for the camera somewhere on the campus of the University of Michigan. The picture was taken at an annual physics conference in Ann Arbor during the summer of 1939.

I recognized two of the men: one, Werner Heisenberg, would go on to spearhead Adolf Hitlers atomic bomb program, the other, Enrico Fermi, would become a top Manhattan Project scientist working on the Allied atom bomb. A third, whom I didnt recognize, Samuel Goudsmit, would become a top Allied intelligence officer tasked with gathering information on the German atom bomb and, in the final months of the war, capturing Hitlers atomic scientists before the Soviets could nab them.

I later learned, to my surprise, that the three were longtime friends and that Heisenberg also knew Robert Oppenheimer, the future scientific director of The Manhattan Project. That photo, taken just a month before the start of World War II, provided the inspiration for Chasing Heisenberg: The Race for the Bomb.

My interest in the rivalry between Allied and German scientists dates back to 1993 when I produced a report on J. Robert Oppenheimer for The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour on PBS. Ive been reading about that history off and on for years, looking for a compelling narrative that would breathe new life into what was arguably one of the greatest scientific and engineering feats of the twentieth century. That 1939 photo alerting me to Heisenbergs friendship with Fermi, Oppenheimer and Goudsmit showed me the way. I thought I knew the bombs history fairly well before I began digging into the lives of those four men, but I was wrong. My research uncovered twists and turns and fascinating details I had not known before, and along with them, the makings of a great story.

CHAPTER ONE

A SMALL GLOBAL COMMUNITY

3-13-38 CBS RADIO WORLD NEWS ROUNDUP

AUSTRIAN INVASION

Tonight the world trembles... Right at this moment Austria is no longer a nation, but is now officially a part of the German empire... The Nazis are driving with all their might to bring Austria under complete Nazi domination... Jews, Catholic leaders and former Austrian officials are being jailed.

Hitler... is preparing... a roundabout triumphal tour of the land of his birth... In Berlin, Field Marshal Herman Goering has served notice that Germany intends to go after the Germans in Czechoslovakia already ringed on several sides by German troops.

BY THE SUMMER OF 1939, a little over a year after that radio broadcast, Adolf Hitler had all but shredded the Versailles Treaty, the peace agreement ending World War I. While Germanys erstwhile enemies sat idly by, hed rebuilt his nations military, sent German troops into the demilitarized Rhineland, annexed Austria, bullied the Czechs into surrendering the Sudetenland, occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia and stripped German Jews of their civil rights, forcing many to flee the country.

After years of grabbing territory through political chicanery, Adolf Hitler was ready to go to war; his plan, to create a Third Reich, a racially pure Germanic Empire in Europe.

As the date for the opening attack, an invasion of Poland, neared, scientists attached to the German War Office began research on a revolutionary weapon, a bomb that would draw its destructive power not from conventional man-made explosives like TNT, but from a primordial energy locked deep inside the uranium atom. No one had ever tried to harness that energy. No one knew if the weapon would work. But if it did, one atomic bomb would be able to destroy an entire city. Loaded into a long-range strategic bomber or onto a guided rocket, it might spread Nazism across the globe.

With the world on the brink of war, Werner Heisenberg, a 37-year-old physics professor at the University of Leipzig, a Nobel Prize-winner and future architect of Hitlers nascent atom bomb program, boarded an ocean liner and set sail for New York City. Heisenberg was one of the most brilliant physicists of his time. His work in the field of Matrix Mechanics was considered every bit as revolutionary as that of Albert Einstein and his theory of relativity.

A loyal son of the fatherland and a corporal in the reserve force that supported Germanys regular army, Heisenberg sympathized with the Nazi goal of restoring Germany to a position of prominence in Europe.

At the time, there were only about a hundred scientists in the world doing research in Heisenbergs field of theoretical physics.

Gttingen was the world capital for theoretical physics. Oppenheimer had come there to study in 1927. He had read and admired Heisenbergs work and looked forward to meeting him. Heisenberg was teaching elsewhere at the time, but when he came to the campus for a short visit Oppenheimer sought him out and introduced himself. Both men had brilliant and original minds. Drawn together by their shared interest, the future rivals developed what may not have been a friendship, but was certainly a relationship built on mutual respect.

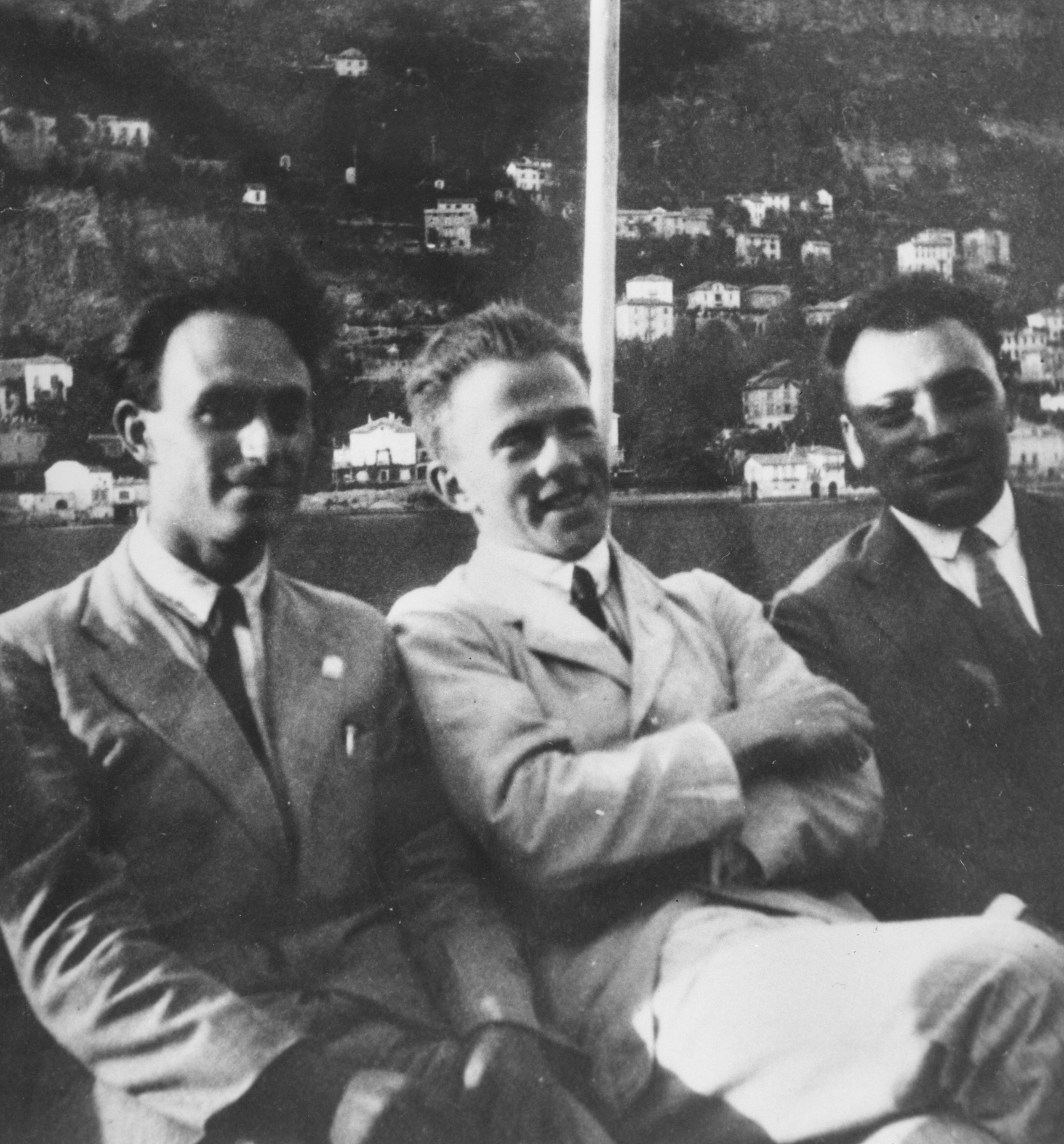

During his trip Heisenberg reconnected with another former Gttingen student, Enrico Fermi, a Nobel Prize-winning Italian physicist. Fermis seven months at Germanys elite university had been difficult. He felt uncomfortable and insecure. Gttingen attracted the worlds brightest physicists, future Nobel Laureates like Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli. Fermi worried that he would not measure up. Nevertheless, he and Heisenberg became close friends.

Enrico Fermi, Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli

(Photograph by Franco Rasetti, Courtesy AIP Emilio Segr Visual Archives, Segr Collection)

The two reunited at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where they attended an annual meeting of theoretical physicists. A photo taken at the time captures the moment. It shows them with three Michigan faculty members: Samuel Goudsmit, Clarence Yokum and Edward Kraus. Goudsmit, another Gttingen graduate, was a close friend of Heisenberg.

Samuel Goudsmit, Clarence Yokum, Werner Heisenberg, Enrico Fermi and Edward H. Kraus at the University of Michigan, summer 1939

(AIP Emilio Segr Visual Archives, Crane-Randall Collection, Goudsmit Collection)

Heisenbergs last trip to the annual summer meeting was in 1939. Two years later, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor thrust him and his three American friends into the front lines of World War II where they squared off against each other in a race to build the atom bomb.