OH PURE AND RADIANT HEART

OH PURE AND RADIANT HEART

Lydia Millet

Soft Skull Press

Brooklyn, NY | 2005

Oh Pure and Radiant Heart

2005 Lydia Millet

Book Design: David Janik

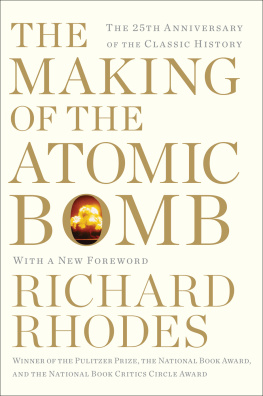

Cover Art: Trinity 2 (21kt, NM, 16.Jul.1945) Copyright 19952003

Gregory Walker (), Creator of Trinity Atomic Web Site.

Author Photo: Adam Frank

Published by Soft Skull Press

71 Bond Street

Brooklyn, NY 11217

Distributed by Publishers Group West

1.800.788.3123

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Millet, Lydia, 1968

Oh pure and radiant heart / Lydia Millet.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-593763-13-8

1. Oppenheimer, J. Robert, 1904-1967Fiction. 2. Fermi, Enrico, 1901-1954Fiction. 3. Nuclear physicistsFiction. 4. Women librariansFiction. 5. Santa Fe (N.M.)Fiction. 6. Szilard, LeoFiction. 7. CelebritiesFiction. 8. Atomic bombFiction. 9. Time travelFiction. I. Title.

PS3563.I42175O37 2005

813.54dc22

2005001028

Behold, I have set before you an open door, and no man can shut it.

Revelation 3:8

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their insight and critical help I wish to thank Jenny Offill, Kieran Suckling, and Kate Bernheimer. For their forbearance as readers, my thanks to Saralaine Millet and Maria Massie. And I am deeply grateful to Richard Eoin Nash for his perseverance and conviction.

For her help with the Japanese language and her hospitality in Tokyo, thanks to Nerissa Moray; for help and guidance in Hiroshima, thanks to Andrew Hill; and for her many social connections, thanks to Alycia Rossiter. For their kindness and interpretive skills, thanks to Kazue Moshi Ichi in Hiroshima and Keiko Shirahama in Nagasaki. Thanks to Hibakusha Tomei Ozaki for his eyewitness account of the bombing of Nagasaki.

Thanks also to Tonya Turner-Carroll and Michael Carroll for their gracious hospitality in Santa Fe, to Debbie Bingham for her help at the White Sands Missile Range, and Peter Galvin and Melanie Duchin for their knowledge of the Grateful Dead. I am also grateful to Brian Segee for his advice on Freedom of Information Act matters, Evelin and Mike Sullivan for their assistance with particle physics, and Ernest B. Williams, tour guide at the Nevada Test Site, for his inspiration.

1

I n the middle of the twentieth century three men were charged with the task of removing the tension between minute and vast things. It was their job to rend asunder the smallest unit of being known to be separable from itself; out of a particle so modest there are billions in a single tear, in a moment so brief it could not be perceived, they would make the finite infinite.

Two of the scientists were self-selected to split the atom. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi had chosen long before to work on the matter, to follow in the footsteps of Marie Curie and her husband, who had discovered radioactivity.

The third man was a theoretical physicist who had considered the subject of the divisible atom among many others. He was a generalist, not a specialist. He did not select himself per se, but was chosen for the job by a soldier.

Thousands worked at the whims of these men. From Szilard they took the first idea, from Fermi the fuel, from Oppenheimer both the orders and the inspiration. They built the first atomic bomb with primitive tools, performing their calculations on the same slide rules schoolchildren were given. For complex sums they punched keys on adding machines. Their equipment was clumsy and dull, or so it would seem by the standards of their children. Only their minds were sharp. In three years they achieved a technological miracle.

Essentially they learned how to split the atom by chiseling secret runes onto rocks.

And it should be admitted, the concession must be gracefully made: in the moment when a speck of dust acquires the power to engulf the world in fire, suddenly, then, all bets are off.

Suddenly then there is no idea that cannot be entertained.

O n a clear, cool spring night more than half a century after the invention of the atom bomb, a woman lying in her bed in the rich and leisured citadel of Santa Fe, New Mexico, had a dream.

This itself was not surprising.

To be precise it was less a dream than an idea in the struggle of waking up. She thought the dream as she began to rouse herself and she was left, after waking, with an urgency that had no answer. She was left salty and dry, trussed up in a sheet, the length of her a shudder of vague regret.

In the dream a man was kneeling in the desert.

The man was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Father of the Atom Bomb. The desert was an American desert: it was the New Mexico desert, and the site was named Trinity. Oppenheimer named it that. He gave lofty names to all his works, all except Fat Man and Little Boy.

These details would be revealed to her later. At the time nothing had a name but the man.

The mans porkpie hat was tipped forward on his head and his pants were torn. His knobby knees were scratched and the abrasions were full of sand. She almost thought she could feel the sand against her own raw flesh, where the grains agitated. It may have been dust on the sheet beneath her, or, further removed, dust between the sheet and the mattress, a pea dreamed by a princess.

He was bent over abjectly, his face turned to the ground.

Then there was the flash, as bright as a thousand suns, which turned night into day. And on the horizon the fireball rose, spreading silently. In the spreading she felt peace, peace and what came before, as though the country beneath her, with its wide prairies, had been returned to the wild. She saw the cloud churning and growing, majestic and broad, and thought: No, not a mushroom, but a tree. A great and ancient tree, growing and sheltering us all.

The sight of it was poetry, the kind that turns mens bones to dust before their hearts.

At this point in the scene she confused it with the Bible. The man named Oppenheimer saw what he had made, and it was beautiful. But when he looked at it, the light burned out his eyes and turned him blind.

She saw the rolling balls of the eyes when he righted himself to face the tree, and they were white like eggs.

B ack then she knew nothing about Oppenheimers life: not who he was, not the identities of places, not the fact that the sand in the scrapes in his knees would have been the sand of the valley with the Spanish name Jornada del Muerto, Voyage of the Dead. There were infinite details she could not recognize, infinite details beyond her awareness in her own half-idea, in the deep blind territory of what is not known to be known but is known all the same.

Also there was what she knew without knowing why she knew it, for example the phrase brighter than a thousand suns. She recalled these words without a hint of where they came from or how they had first been imprinted on her memory. She did not know what brighter than a thousand suns would mean, how a brightness so bright could be outdone. The eye is not equal to even one sun, she thought. Straight, unwavering, bold, the eye cannot abide it.

A thousand suns? The eye could never adapt.

Or maybe once it is blinded the eye is transformed, she thought, and ceases to be an eye at all.

Next page