Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To immigrants, then and now

This book has been written with the support and encouragement of many people and we are in their debt. A word or two of heartfelt gratitude is much deserved.

First of all, thanks to Sir Christopher Llewellyn Smith, who in 1996 planted the original idea of a book about Enrico Fermi into Ginos mind, thinking undoubtedly that Italian physicists need to stick together. Then to the family historian, Olivia Fermi, who has kept her grandparents legacy alive by an open cultural dialogue (see the Neutron Trail website). Her enthusiastic support of our book was also reflected in lengthy and often moving interviews with other members of the Fermi family: Sarah Fermi, the widow of Fermis son, Judd (Giulio); and Rachel Fermi, Enrico and Lauras youngest granddaughter. Ginos cousin Fausta Walsby shared some childhood memories of the Fermi family from their overlapping time in Los Alamos with her parents, Emilio and Elfriede Segr. And more background was generously provided by Robert Fuller, who regarded Judd Fermi as his best friend. Our meeting in Ithaca with Rose Bethe and her son Henry also provided invaluable anecdotes of the Fermi history.

We particularly want to acknowledge the kindness and insights of Ugo Amaldi, himself a physicist, who spent the greater part of a day with us in Geneva, speaking about Fermi and his family, lifelong friends of his parents, Edoardo and Ginestra Amaldi. Several follow-up communications offered an even richer rendering of this friendship and a talk with Ugos brother, Francesco, was helpful in filling a few blanks in the picture.

In Rome, we were delighted to have a personal tour of the Fermi museum at the university, as well as repeated help with our research from the historian Adele La Rana. Thanks also to the historian Giovanni Battimelli who offered us advice, guided us with his own writings, and provided precious access to other documents. We benefited in Pisa from the counsel of Roberto Vergara Caffarelli and the Domus Galilaeanas welcome, where the able assistance of Maura Begh in gaining access to its Fermi Archives was greatly valued.

Special thanks also go to the courteous and more than competent archivists Diane Harper and Barbara Gilbert at the Regenstein Library of the University of Chicago and to Savannah Gignac at the Emilio Segr Visual Archives of the American Institute of Physics. For the American part of this book, the trip that Ellen Bradbury Reid arranged for us a few years ago to Trinity, the site of the first atom bomb explosion, lent extra poignancy to this story.

Several esteemed physicists contributed astute observations and comments regarding Fermi and his collaborators. The list includes Harold Agnew, Jeremy Bernstein, Frank Close, Freeman Dyson, Kenneth Ford, Jerry Friedman, Richard Garwin, and Murray Gell-Mann. We are especially grateful to two distinguished physicists, Kenneth Ford and Alfred Goldhaber, who have read the manuscript in galley form, giving us valuable advice and pointing out errors. Needless to say, any remaining errors are purely our own fault.

We were lucky to have an editor, Serena Jones at Henry Holt, who was a strong believer in the importance of telling this story and guided the writing of it with a gentle and deft hand. And special thanks to Molly Bloom and Emily DeHuff, whose meticulous edits improved the manuscript. We are also grateful to Katinka Matson and John Brockman, literary agents who continue to find imaginative and creative ways of making the world of science accessible to a larger public.

And finally, many thanks to Doron Weber and to the A. P. Sloan Foundations program in the Public Understanding of Science, Technology and Economics for providing the means to travel and absorb the many influences on Fermis life. This book benefited enormously from their support.

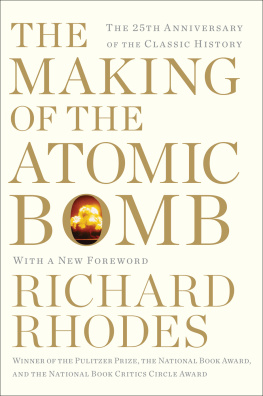

July 16, 1945. Dawn broke reluctantly, the early rays of the day barely grazing the tops of nearby peaks. It was almost as if the sun sensed that its brightness would be outshone. A group of scientists, huddled together against the morning chill, set aside their worries about bad weather and concentrated on the seismic event that was about to occur.

The countdown began at 5:09:45 a.m. If all went according to plan, exactly twenty minutes later they would throw a switch triggering the detonation of the worlds first atom bomb. The tension at the site was palpable as they waited. An earthen mound above a concrete slab roof, all supported by massive oak beams, fortified the structure they were staying in. Located ten thousand yards south of the hundred-foot-high tower holding the bomb, the shelter was thought to be safe no matter how large the explosion at Ground Zero might be. The small group who manned the Trinity Project, as it was named, included George Kistiakowsky, the head of explosives, Kenneth Bainbridge, the man who had selected and built up the site, and of course J. Robert Oppenheimer.

General Leslie Groves, feeling that he and Oppenheimer should not be together in case of disaster, had gotten into his jeep a little earlier and driven five miles south to Base Camp, leaving his military deputy in charge at the bunker. Most of the physicists who had worked on Trinity were at Campania Hill, some twenty miles northwest of Ground Zero. A few, including Enrico Fermi and Emilio Segr, were ten miles closer, at Base Camp. Shallow trenches had been dug there to protect them, but would those trenches be enough? Everybody thought yes, but how big was the blast going to be? Might it even be a complete failure?

A few days earlier the senior physicists had started a betting pool about the blasts magnitude; a one-dollar entrance fee built up the pot. Kistiakowskys wager had been one thousand tons of TNT equivalent, a low estimate, as he would discover when he climbed on top of the bunker after the blast, only to be knocked over by the shock wave that reached him a few seconds later. Hans Bethe, head of the theory division, had said eight thousand, while a worried Oppenheimer had settled for a modest three hundred.

The switch was thrown at 5:29:45. Many recorded their impressions of what happened next, an event subsequently described as brighter than a thousand suns. From base camp, Isidor Rabis memory was that Suddenly there was an enormous flash of light, the brightest light I have ever seen or that I think anyone has ever seen. It blasted, it pounced: it bored its way right through you. It was a vision that was seen with more than the eye. The flash was so overwhelmingly intense that irrational instants of fear were common. For a moment I thought the explosion might set fire to the atmosphere and thus finish the earth, even though I knew this was not possible, Segr recalled.

Seconds later, as the mushroom cloud began rising in the sky, those watching it were left trying to grasp the meaning of what they were witnessing. Oppenheimer remembered the lines from the Bhagavad Gita s scriptures coming to him: I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds. Bainbridge expressed himself in much more prosaic language: Now we are all sons-of-bitches.

Fermi was arguably the physicist most responsible for the world-changing event that had just occurred in the New Mexico desert. There is no documentation of what he was thinking at the time. But there is a record of what Fermi was doing. If you didnt know him, it would seem bizarre, but everybody knew he always acted with purpose. A few seconds after the blast, Fermi stood up and began tearing a large sheet of paper into small pieces and then dropping them from his upraised hand. Forty seconds later, as the front of the shock wave hit, the midair pieces were blown a short distance away. Pacing off the distance to where they landed, some eight feet, he consulted a little chart he had prepared beforehand. Shortly afterward, Fermi told those around him that he estimated the blasts force as roughly equivalent to ten kilotons of TNT.