Contents

Guide

Page List

THE APOCALYPSE FACTORY

PLUTONIUM AND THE MAKING OF THE ATOMIC AGE

STEVE OLSON

For Lynn, again,

and in memory of John Hersey

The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation provided support for the

writing of this book through its Public Understanding of

Science, Technology, and Economics program.

Apocalypse: A prophetic revelation of future events.

... Have you ever held plutonium

in your hand? Someone once gave me a piece shaped and nickel-plated

so alpha particles couldnt reach the skin. It was the temperature, you see,

the element producing heat to keep itself warmnot for ten

or a hundred years, but thousands of years. This is the energy contained

in Hanfords fuel. I think of that place as a song not properly sung.

A romantic song. And not one person in a hundred knows the tune.

Kathleen Flenniken,

A Great Physicist Recalls the Manhattan Project

CONTENTS

THE APOCALYPSE FACTORY

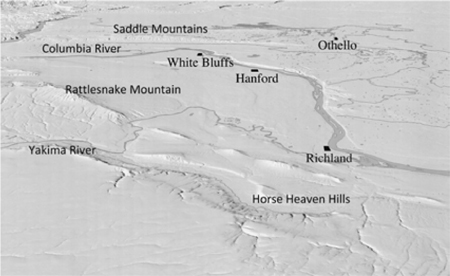

AS SOON AS FRANKLIN MATTHIAS FLEW OVER THE HORSE HEAVEN Hills, he knew hed found what he was looking for. Spread out below him was a barren, wind-swept plain. The Columbia River, running cold and deep, separated the plain from higher ground to the north and east. To the west the top of Rattlesnake Mountain was covered by snow, but the rest of the land, tinted gray-green by sagebrush, was snow-free, even on this first day of winter.

Matthias, a 34-year-old colonel in the US Army Corps of Engineers, went through the checklist hed gotten from the engineers at DuPont. The Columbia could provide plenty of clear, cold water for the reactors. A row of spindly metal towers carried high-voltage lines from Grand Coulee Dam, which had come online just the year before. Not far from the towers, a spur line from the Milwaukee Road emerged from the gap where the Columbia cut through the Saddle Mountains. DuPont could haul equipment, construction materials, and chemicals down the rail line to the site.

The plain was at least twice as large as the 12-mile by 16-mile expanse that the engineers had demanded, and no large towns were nearby. If one of the reactors blew up, relatively few people would be killed. And on that December 22, 1942, with the sun low on the horizon and silvered by clouds, the land looked sere and forlorn. A few scraggly townsRichland, Hanford, and White Bluffs, according to the mapinterrupted the treeless expanse, along with some bedraggled farms. But the number of people who would have to move couldnt be more than a thousand or two. This is it, Matthias thought. Theres nothing like it in the country.

Matthias was looking for a place to build a facility that he had been told could end World War II. Four years earlier, two chemists working in a laboratory a few miles away from Hitlers Berlin headquarters, with the invaluable help of an Austrian physicist living in exile in Sweden, had announced that atoms of uranium could split and release immense quantities of energy. Alarmed that Nazi Germany would use the discovery to build atomic bombs, the United States had launched a crash program, dubbed the Manhattan Project, to build them first. Even as Matthias was flying over the towns of Richland, Hanford, and White Bluffs, workers were clearing a vast tract of land in eastern Tennessee, near a sharp rise of land known as Black Oak Ridge, where a massive factory to create bomb-making materials would rise over the next two years. On the flanks of an extinct volcano in New Mexico, other workers were converting a boys school in the tiny hamlet of Los Alamos into a top-secret laboratory, where many of Americas leading scientists would soon congregate to assemble the raw materials of the atomic age into weapons of unprecedented power.

Los Alamos and, to a lesser extent, Oak Ridge have gotten most of the attention in histories of the Manhattan Project. Thats understandable. The Oak Ridge facility produced the material in the first atomic bomb used in warfare, the one dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. The scientists at Los Alamos accomplished in a few short years work that would normally have taken much longer.

But in this book I argue that the Hanford nuclear reservation in south-central Washington State is the single most important site of the nuclear age. Hanford produced the material in the first atomic bomb ever exploded, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. The first full-scale nuclear reactor was built at Hanford, and all subsequent reactors have used ideas and technologies developed there. The last atomic bomb used in warfarethe one dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945contained nuclear material manufactured at Hanford.

The Hiroshima bomb was a technological one-off. No subsequent bombs used that design, except for a few artillery weapons that were soon discarded. At the core of every nuclear weapon in the world today is a small pit of radioactive material made either at Hanford or at a comparable facility elsewhere in the world.

Hanford and its successor facilities have given us, for the first time in history, the ability to destroy ourselves and everything we have ever created. Understanding what happened at the site that Colonel Matthias chose on that solstice day in December 1942 may give us a way to avoid that fate.

IF MATTHIAS HAD LOOKED through the window of his reconnaissance plane toward the northeast, he would have seen a distant gray smudge on the horizon. Thats the town of Othello, Washington, where I grew up in the 1960s and early 1970s. I had an idyllic, all-American childhood in Othello. In those days of laissez-faire parenting, my friends and I, on weekends and in the summer, were free to do pretty much anything we wanted once wed finished a few chores. We could ride our bikes to the swimming holes outside town, to the strange rock formations carved into the desert by prehistoric floods, sometimes all the way to the Tri-Cities, 60 miles to the south, on the banks of the Columbia River. We congregated at Othellos many parks to play baseball, at the drugstore to read comics, and at the one-room library adjacent to city hall. In rosy hindsight, I remember Othello as an isolated, self-contained paradise where we were free to make our own mistakes and enjoy our own triumphs.

If I hadnt lived in Othello, I could have written almost exactly the same book as you hold in your hands. Then again, if I hadnt lived in Othello, this book might never have been written. Hanford and Nagasaki have always been the neglected stepchildren of World War II. Some people might have heard of Hanford as the most contaminated nuclear site in the Western Hemisphere, or as the location of a multi-billion-dollar Department of Energy cleanup, but they probably havent heard much else. In Japan, residents of Nagasaki often wonder why Hiroshima gets so much more attention than the city on which the second bomb was dropped. Throughout the world, people tend to speak of the bomb, rather than the bombs, as if the two quite different bombs dropped on Japan can all be captured in a single abstract image.

The first time Colonel Franklin Matthias saw the barren stretch of land extending from Richland to White Bluffs in south-central Washington State, he knew it would be perfect for the plutonium production facilities that came to be known as Hanford. The distance from Richland to White Bluffs is about 30 miles.