MERIDIAN

Crossing Aesthetics

Series founded by the late Werner Hamacher

Editor

WHAT IS REAL?

Giorgio Agamben

Translated by Lorenzo Chiesa

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

English translation 2018 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

What Is Real? was originally published in Italian in 2016 under the title Che cos reale? La scomparsa di Majorana 2016, Neri Pozza Editore.

This book was negotiated through Agnese Incisa Agenzia Letteraria, Torino.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Agamben, Giorgio, 1942 author.

Title: What is real? / Giorgio Agamben ; translated by Lorenzo Chiesa.

Other titles: Che cos reale? English

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2018. |

Series: Meridian: crossing aesthetics | Originally published in Italian in 2016 under the title Che cos reale? La scomparsa di Majorana.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018011743 (print) | LCCN 2018014658 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503607378 | ISBN 9781503606203 | ISBN 9781503606203 (cloth :alk. paper) | ISBN 9781503606210 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Majorana, Ettore. | Nuclear physicistsItaly. | Missing personsItaly. | Quantum theory.

Classification: LCC QC774.M34 (ebook) | LCC QC774.M34 A66 2018 (print) | DDC 530.092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018011743

Cover design: Rob Ehle

Cover photograph: Ettore Majorana, Wikimedia Commons

Contents

What Is Real?

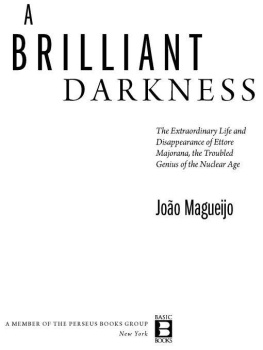

1. On the night of 25 March 1938, at 22:30, Ettore Majorana, who was regarded as one of the most talented physicists of his generation, boarded a Tirrenia steamer in Napleswhere he had held the chair of theoretical physics for a yearheading for Palermo. In the words of the announcement published on 17 April in the Chi lha visto? column of the Domenica del Corriere, from that moment, except for unconfirmed reports and conjectures, every trace of the thirty-one year old professor, 170 cm tall, lean, dark hair and eyes, with a long scar on the back of his hand was lost. In spite of searches involving the police authorities and, under pressure from Enrico Fermi, the head of government in person, Ettore Majorana had disappeared forever. His relatives never accepted the possibility of suicide, which in itself seemed to convince the police that he had killed himself, and did not apply for a declaration of presumed death, as is usual in these circumstances. Unverifiable legends then circulated about the scientists escape to Argentina or Nazi Germany, his retreat to a monastery, and reappearance as a tramp in Sicily and Rome in the 1970s.

Every reflection on his disappearance should start from the letters Majorana wrote on the very day of his departure and the next as the only indisputable documents. A careful analysis of the texts shows that, at the very moment when he decides to disappear, Majorana seems to suggest divergent explanations for his gesture, as if he wanted to cover his tracks, intentionally leaving it open to contrasting interpretations.

On the same day of his departure he writes the following letter to Carrelli, his colleague at the University of Naples:

Dear Carrelli, I have made a decision that was by now inevitable. It does not contain a single speck of selfishness; but I do realize the inconvenience that my sudden disappearance may cause for the students and yourself. For this, too, I beg you to forgive me; but above all for having betrayed the trust, the sincere friendship and the sympathy you have so kindly offered me over the past few months. I beg you also to remember me to all those I have come to know and appreciate at your Institute, in particular Sciuti; of all I shall preserve the dearest memories at least until eleven oclock this evening, and possibly later too.

Majorana refers to the act he is carrying out as my sudden disappearance, not as a suicide, and shortly after specifies that he will remember his friends from the Institute of Physics until eleven oclock this evening, and possibly later too. His intention to insinuate discordant explanations is already evident; until eleven oclock may indeed refer to an anticipation of death, but, as has been observed, it is highly unlikely that, having the whole night ahead of him, he intended to jump in the sea half an hour after departing, when the sailors and passengers were still awake on the decks and would certainly have seen him. From this standpoint, the possibly later too is even more misleading, as it seems to contradictalthough only hypotheticallyevery idea of suicide. Moreover, we should highlight the claim about the absolutely non-subjective motivation for his decision (it does not contain a single speck of selfishness). That Majorana was actually not thinking about suicide seems to be proved by the only other fact that is certain: before setting off, he withdrew a considerable amount of money and brought his passport with him.

On the other hand, the letter he leaves at the hotel for his parents reads like a suicide note, although death is curiously evoked only through its repercussions with respect to dress codes: I have only one desire: that you do not wear black. If you want to follow custom, then bear some sign of mourning but not for more than three days. After that, if you can, remember me in your hearts and forgive me.

On 26 March, Carrelli received a laconic telegram that contradicted the letter Majorana had just sent and promised a new one: Dont get alarmed. Letter to follow. Majorana. The new letter, dated Palermo 26 March 1938-XVI (we should notice the reference to the Fascist Era, as if it were an official document), in fact announced the imminent return of the missing person:

Dear Carrelli, I hope you got my telegram and my letter at the same time. The sea rejected me and I will be back tomorrow at the Hotel Bologna traveling perhaps with this letter. However, I intend to give up teaching. Do not think I am like an Ibsen heroine, because the case is different. I am at your disposal for further details.

Once again the allusion to the seas rejection may suggest an abandoned intention to commit suicide (but also the intention to embark upon a sea voyage); however, the decision to disappear is now replaced by the decision to give up teachingwhich is presented as somehow equivalent. As in the first letter where disappearance is at stake, emphasis is being placed on the non-psychological motivations for this resignation (Do not think I am like an Ibsen heroine, because the case is different). The case is different; Majorana implicitly suggests to his friend that it is a matter of understanding the particular nature of the case in question.

Majoranas behavior duly disproved even the content of this letter. Although according to the shipping line the return ticket had been used and a nurse who knew him said she had glimpsed him on a street in Naples, Majorana did not return to the Hotel Bologna nor did he show up at the university to resign from his position. Now he had truly disappeared forever.

The first conclusion we can draw from the examination of the letters is that the reality of facts never duly corresponds to the reality they evoke, which in turn lends itself to divergent interpretations, of which the author could not be unaware. Majorana did not disappear after the first letter, which announced his final parting, and did not reappear after the second, which communicated his reappearance. Nor did he kill himself, as seemed implicit in the letter to his relatives. However, the only certain thing is that he actually and irrevocably disappeared, and that he relinquished his position in theoretical physics in an equally irrevocable manner, but in both cases in ways other than those suggested by the letters.

Next page