THE KINGDOM AND

THE GLORY

MERIDIAN

Crossing Aesthetics

Werner Hamacher

Editor

Translated by Lorenzo Chiesa

(with Matteo Mandarini)

Stanford

University

Press

Stanford

California

2011

THE KINGDOM AND

THE GLORY

For a Theological Genealogy o f Economy

and Government (Homo Sacer II, 2)

Giorgio Agamben

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

English translation 2011 by the Board of Trustees of the

Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

The Kingdom and the Glory was originally published in Italian under the title Il Regno e la Gloria. Per una genealogia teologica delleconomia e del governo. (Homo Sacer II, 2)

Giorgio Agamben 2007.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Agamben, Giorgio, 1942 author.

[Regno e la gloria. English]

The kingdom and the glory : for a theological genealogy of economy and government / Giorgio Agamben ; translated by Lorenzo Chiesa (with Matteo Mandarini).

pages cm. (Meridian, crossing aesthetics)

Originally published in Italian under the title Il Regno e la Gloria.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8047-6015-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8047-6016-4 (pbk : alk. paper)

1. Religion and politics. 2. Power (Philosophy) 3. Political sciencePhilosophy. I. Chiesa, Lorenzo, translator. II. Mandarini, Matteo, translator. III. Title. IV. Series: Meridian (Stanford, Calif.)

BL65.P7A3313 2011

201.72dc22

2010043992

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8047-8166-4

Translators Note

and the Appendix were drafted by Matteo Mandarini and revised by Lorenzo Chiesa.

In accordance with the authors request, after prior consultation of the original works, all quotations were translated into English in line with his own translation into Italian, with the notable exception of works originally published in English. This also applies to works currently available in English translation, in which case translations were consulted, incorporated, and, where appropriate, modified. Significant phrases and sentences that do not appear in the existing English translations are indicated in braces. I have used the same method to signal the few instances in which the authors personal translation and the English version differ substantially. Page references refer to the English translation or, failing this, to the original.

I wish to thank Giorgio Agamben, Tom Baldwin, Emily-Jane Cohen, Mike Lewis, Frank Ruda, Danka tefan, and Alberto Toscano for their valuable suggestions and for their help in securing access to sources that proved difficult to obtain.

Oeconomia Dei vocamus illam rerum omnium administratione vel gubernationem, qua Deus utitur, inde a conditio mundo usque ad consummationem saeculorum, in nominis sui Gloriam et hominum salutem.

J. H. Maius, Oeconomia temporum veteris Testamenti

Chez les cabalistes hbreux, malcuth ou le rgne, la dernire des sphiroth, signifiat que Dieu gouverne tout irresistiblement, mais doucement et sans violence, en sorte que lhomme croit suivre sa volont pendant quil excute celle de Dieu. Ils disaient que le pech dAdam avait t truncatio malcuth a ceteris plantis; cest--dire quAdam avait rentranch la dernire des sphires en se faisant un empire dans lempire.

G. W. Leibniz, Essais de thodice

We must then distinguish between the Right, and the exercise of supreme authority, for they can be divided; as for example, when he who hath the Right, either cannot, or will not be present in judging trespasses, or deliberating of affaires: For Kings sometimes by reason of their age cannot order their affaires, sometimes also though they can doe it themselves, yet they judge it fitter, being satisfied in the choyce of their Officers and Counsellors, to exercise their power by them. Now where the Right and exercise are severed, there the government of the Commonweale is like the ordinary government of the world, in which God, the mover of all things, produceth natural effects by the means of secondary causes; but where he, to whom the Right of ruling doth belong, is himselfe present in all judicatures, consultations, and publique actions, there the administration is such, as if God beyond the ordinary course of nature, should immediately apply himself unto all matters.

Th. Hobbes, De Cive

While the world lasts, Angels will preside over Angels, demons over demons, and men over men; but in the world to come every command will be empty.

Gloss on 1 Corinthians 15:24

Acher saw the angel Metatron, who was given permission to sit down and write the merits of Israel. He then said: It is taught that on high there will be no sitting, no competition, no back, and no tiredness. Perhaps, God forbid, there are two powers in heaven.

Talmud, Hagiga, 15 a

Sur quoi la fondera-t-il lconomie du Monde quil veut gouverner?

B. Pascal, Penses

Preface

This study will inquire into the paths by which and the reasons why power in the West has assumed the form of an oikonomia, that is, a government of men. It locates itself in the wake of Michel Foucaults investigations into the genealogy of governmentality, but, at the same time, it also aims to understand the internal reasons why they failed to be completed. Indeed, in this study, the shadow that the theoretical interrogation of the present casts onto the past reaches well beyond the chronological limits that Foucault assigned to his genealogy, to the early centuries of Christian theology, which witness the first, tentative elaboration of the Trinitarian doctrine in the form of an oikonomia. Locating government in its theological locus in the Trinitarian oikonomia does not mean to explain it by means of a hierarchy of causes, as if a more primordial genetic rank would necessarily pertain to theology. We show instead how the apparatus of the Trinitarian oikonomia may constitute a privileged laboratory for the observation of the working and articulationboth internal and externalof the governmental machine. For within this apparatus the elementsor the polaritiesthat articulate the machine appear, as it were, in their paradigmatic form.

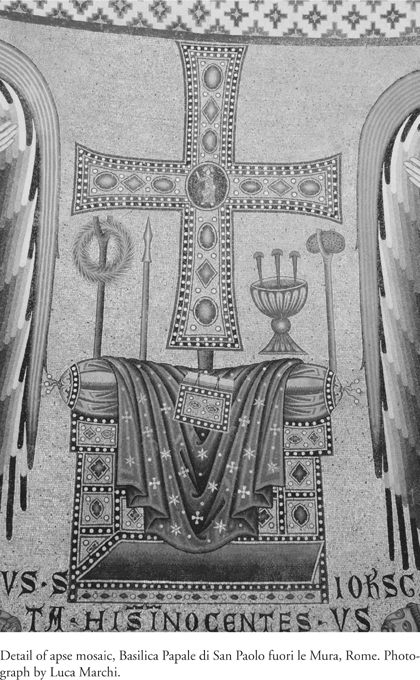

In this way, the inquiry into the genealogyor, as one used to say, the natureof power in the West, which I began more than ten years ago with Homo Sacer, reaches a point that is in every sense decisive. The double structure of the governmental machine, which in State of Exception (2003) appeared in the correlation between auctoritas and potestas, here takes the form of the articulation between Kingdom and Government and, ultimately, interrogates the very relationwhich initially was not consideredbetween oikonomia and Glory, between power as government and effective management, and power as ceremonial and liturgical regality, two aspects that have been curiously neglected by both political philosophers and political scientists. Even historical studies of the insignia and liturgies of power, from Peterson to Kantorowicz, Alfldi to Schramm, have failed to question this relation, precisely leaving aside a number of rather obvious questions: Why does power need glory? If it is essentially force and capacity for action and government, why does it assume the rigid, cumbersome, and glorious form of ceremonies, acclamations, and protocols? What is the relation between economy and Glory?

Next page