Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

A Moment of Fatigue or Moral Discomfort

Your highness: my sons malady has been caused by noble studies.

FROM A LETTER SENT TO MUSSOLINI BY ETTORE MAJORANAS MOTHER

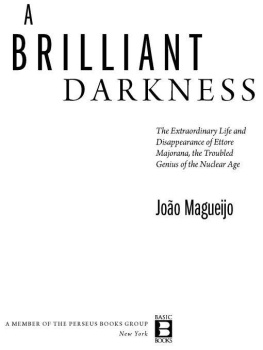

In my early twenties, when I was still an apprentice scientist, I regularly worked as a scientific secretary at the Ettore Majorana Center in Sicily. This was always at the height of summer, when a brutal sun scorches the land, when you cant help but fall in love with the exuberant beauty of Sicily, a splendor full of superlatives, be it in the landscape, the people, or the food: Beautiful is never bello in Sicily, its bellssimo; dangerous is never pericoloso, its pericolosssimo.

It was during one of these so-called working trips, as a bunch of us sat outside demolishing yet another bottle of Corvo Rosso, that I first encountered Ettore. I refer to him by his first name now: Hes been with me throughout my scientific career as a shadow Ive never been able to shake off, perpetually reminding me of his story.

It was hardly surprising that Ettores story came up during so many nighttime chats under starry skies: After all, we worked at a center named after him. For our efforts, we would be handsomely rewardedin cashby Il Centro Ettore Majorana. That bottle of wine, we wouldnt be paying for it: The center would settle the matter gracefully. Just as it took care of restaurant meals, nightclub fees, even the beach umbrellas at the nearby lido. If youre on the right side in Sicily, you dont offer payment: It might cause grave offense. And you certainly wouldnt want that.

So Ettore was with us, at least in spirit, and I wasnt surprised to hear that he was not only a talented physicist but a Sicilian, born in the town of Catania. Hed been a nuclear physicist in Enrico Fermis famous research group, the Via Panisperna Boys, a whiz kid who could outdo even Fermi at the hardest calculations. In fact, Fermi compared Ettore to Isaac Newton and Galileo Galilei on a scale on which he considered himself second classand on which he embarrassingly forgot to include Albert Einstein in the first rank.

However, this is not the end of the story. In fact, its not even the beginning. Nowadays, Ettore is best known for something else: his final stunt. Without it, no one would want to know about his life. Hed be yet another victim of the myth that scientists are rational and emotionlessnot real human beings. Hed be known for his theories about the neutrino and his contributions to nuclear physics and quantum mechanics, but nothing more.

Except for his stunt.

On the night of March 26, 1938, when Ettore was thirty-one years old, he boarded a ship in Palermo, Sicily, and was never seen again. He left behind a series of suicide notes and was known to have been depressed for at least five years; but what prevents the case from being closed is that his body was never recovered, and over the next few decades, he was allegedly sighted on numerous occasions. He also took with him the equivalent of $70,000, as well as his passport. Its hard to deny him human status after that.

Over the years, many theories have been proposed to explain what happened to him. Some claim he joined a monastery in Calabria; others that he may have run away to Argentina; still others say (or, rather, whisper) that he might have got into trouble with the Mafia. Conspiracy theorists consider him kidnapped by another political power eager for his nuclear knowledge. The lunatic fringe prefers him abducted by aliens, or perhaps still in flight in the extra dimensions. The fact is that no one really knows.

Naturally, on that Sicilian evening, fueled as we were by Corvo Rosso, and given that we were all budding physicistsa specie endowed with psychotic levels of imaginationwe came up with even more fantastic theories. I recall someone suggesting that hed bedded the Pope and been killed by a Vatican bodyguard.

But in all seriousness, Ettores story still fascinated me the next morningand has fascinated me ever since. The more I found out about him, the more relevant I found the issues raised by the story of his life. Over time, I became interested in more than just what happened to him; I became hooked on the question, what drove him to disappear? As my career progressed and I felt more acutely the many conflicts affecting scientists, the more I understood Ettore. Back in 1991, I was a raving idiot, too happy to be knowledgeable, too keen to be true. My feelings about Ettore grew with me as I matured and started to question the sanity of scientists myself. Until I began referring to him by his first name.

Ettore Majorana was born in Catania, on the eastern coast of Sicily, on August 5, 1906, at 8:15 pm. His early days were those of a child genius, a prodigy, a gift from God. Having revealed a precocious ability with numbers, little Ettore was often paraded before visitors, doing cubic roots in his head, while the other kids were out playing marbles. He was never allowed to play and bore the corresponding solitude along with his brilliance.

In 1928, he abandoned conventional studies in civil engineering to become a theoretical physicist, at that time regarded as an unhinged pursuit. It was an impulsive act, never fully sanctioned by his family, but the poisonous bait was laid out for him by Enrico Fermi and his friends. Ettore at this time is described as Moorish looking, with intensely black hair and extremely bright eyes; disheveled and shy, constantly pondering, unable to chatthe caricature of a genius.

Now it just so happened that on Via Panisperna in Rome, there was a kindergarten for geniuses: a group of young, extremely bright physicists led by Fermi. They worked at an institute where they were given free rein: They held wagers as to who could solve differential equations the fastest, disputed audacious solutions to the riddle of the atomic nucleus, and dared each other to come up with the craziest theories of the universe. How they shouted... what a racket they made, even considering they were Italians. One day, one of them became so excited he threw a chair at another during an argument on the nature of solar fuel. Deep in their hearts, they were barely adults. In a sense, they were playing with marbles.

When Ettore first arrived at Via Panisperna to meet Fermi, the institute was struggling to solve what is now known as the universal Fermi potential, an essential tool for doing calculations in atomic physics. Fermi had managed to tabulate some regions of the potential, doing a giant number of sums essentially by hand (this was before computers), and although the results looked promising, they were still inconclusive. Fermi explained to Ettore why there were still such gaping holes in his table and why no one had been able to fill them. Ettore asked a few short questions, then left in the enigmatic style that would become his trademark.

The next day he returned and asked Fermi to show him the table again. Ettore then produced a piece of paper, did a few quick calculations, and congratulated Fermi on having made no mistakes. When Fermi looked surprised, Ettore went to the blackboard and wrote out a simple mathematical transformation converting the impenetrable problem into a well-known textbook equation. The picture of the full potential sprang into focus. Jaws duly dropped. Young Ettore was much given to theatricality.