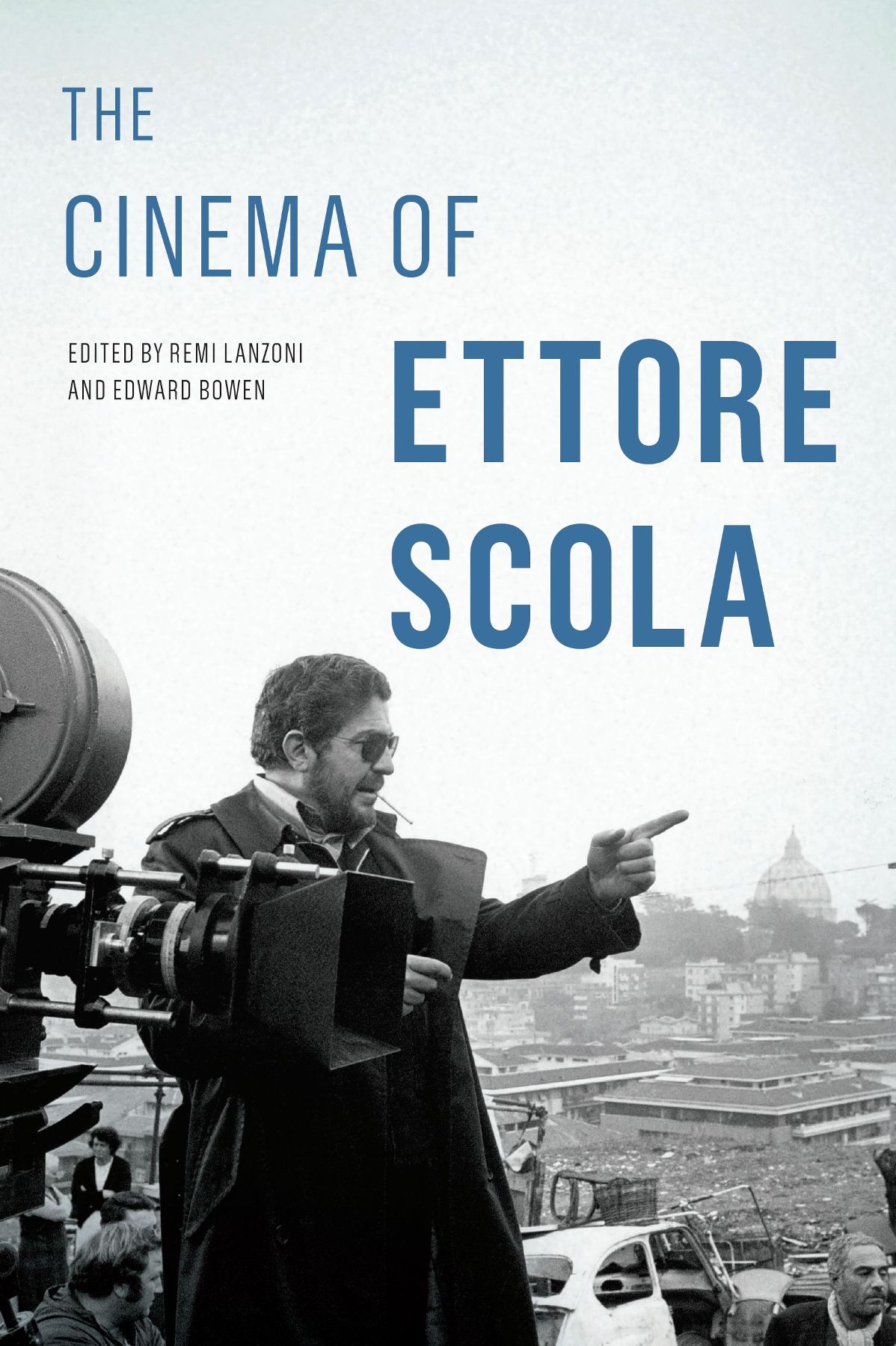

The Cinema of Ettore Scola

Contemporary Approaches to Film and Media Series

A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu.

General Editor

Barry Keith Grant

Brock University

The Cinema of Ettore Scola

Edited by Remi Lanzoni and Edward Bowen

Wayne State University Press

Detroit

2020 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4379-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-8143-4747-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8143-4380-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020931835

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 482011309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

Dedicated to Peter Bondanella

Contents

Edward Bowen and Rmi Lanzoni

Mariapia Comand

Fabrizio Cilento

Rmi Lanzoni

Millicent Marcus

Christian Uva

Pierre Sorlin

Francesca Borrione

Brian Tholl

Emiliano Guaraldo and Federica Colleoni

Marina Vargau

Nicoletta Marini-Maio

Dario Marcucci and Luca Zamparini

Edward Bowen

Gian Piero Brunetta

I am honored to have the privilege of opening this volume on one of the crucial authors of Italian cinema, Ettore Scola. Scola was a true intellectual, both politically involved and fully dedicated to aesthetic research in his work. With Scola, one could easily apply the formula of a postmodern commitment, coined by Pierpaolo Antonello and Florian Mussgnug, a political commitment however commensurate with the new era, dominated by the crisis of ideologies. One important point of the present volume is to underline how the analysis of Scolas cinema should be directed not only to its contents but also and above all to its form. Scola thus becomesas this book recognizesa laboratory case that allows for the application of all the tendencies of contemporary theory on cinema, from ideology to poststructuralism, from gender to genre, from the body to the mask, from the studies on perception and reception to film production.

This being said, it is difficult for me to talk about Ettore Scola from only a scholarly point of view. For me, Ettore was a mentor and an inspirational role model. At the beginning of the new millennium, I organized a retrospective on Scola for the Pesaro Film Festival, and Scola was also my guest at the Teatro Palladium in Rome in one of his last, if not last, public appearances for the Cinema and History conference, where I had the pleasure of speaking extensively with him and about him. We spoke many times about politics and cultural policies, and he insisted that I should not abandon the National Association of Cinema Authors (ANAC) at a time of strong turmoil and scission. For a man of culture like him, political commitment and militant action were essential. He felt bound to that association, which gathered many authors of his generation, from Age and Furio Scarpelli to Leo Benvenuti and Piero De Bernardi (the founders of the commedia allitaliana), from Citto Maselli to Carlo Lizzani and Giuliano Montaldo (some of the fathers of post-neorealist auteur cinema).

Relevant to my thoughts on Scola, there is an expression that was coined by the Sicilian writer Gesualdo Bufalino: la moviola della memoria (the editing machine of memory). Memory, especially for a movie lover, works like a Moviola, the analog machine used for much of the history of cinema to edit films. Like film stock, memory unfolds in a serpentine fashion, sometimes making insalate (salads; in filmic jargon, a tangle of celluloid), and it can be moved forward and backward on a Moviola. It can be used for flashbacks and flash-forwards. That is what I am doing here, exercising my memory on a master filmmaker who also happens to be a familiar character. I would like to start from just a couple of flickering images of my encounters with Scola, which still move me today and in my opinion remain important finds, fragments of both archive and memory. First of all, I recall Scolas famous chat at the Pesaro Film Festival with his friend, exegete, and political companion Lino Miccich, which reappeared in the 2016 documentary on Scola, Ridendo e scherzando (Laughing and Joking, 2016) made by his daughters, Silvia and Paola Scola. There are many elements of interest in that visual testimony, including the role of directing versus screenwriting. Directing is not what interests me the most, Scola affirms in his conversation with Miccich. He explains that the things that impress him most of filmmaking are the story and good screenwriting. The rest comes by itself; it is a natural way of writing for images. In addition, he discusses his own formation as a screenwriter and director, his relationship with Antonio Pietrangeli, the commedia allitaliana, and of course his involvement with politics. It was exciting to see two men of this caliber, one of the greatest directors and one of the best-known critics and cultural operators of Italian cinema, conversing with each other. We experienced, I assure you (for me and the other cameraman who helped me film), a moving atmosphere and the feeling of living a historical moment, especially since the old critic was ill and the elder director had come to pay him homage at his homea gesture that seemed to me of great nobility and generosity.

I will also never forget when Scola, his daughter Silvia, Christian Uva, and I met prior to the Cinema and History conference to prepare a video on the representation of history in his films. At the time, Scolas legs were bothering him, and he stated that the legs go before ones mind; his energy and irony were still intact. Scolas precious legacy still remains in me. It is as if Scola himself had accompanied me in this montage of sequences, even if he did not spare me some of his usual irony: Ettore, I asked, tell me which clips you want to choose for the audience. He simply replied: I meet more and more people who want me to do the work that they have to do. So do your job and you choose the scenes! Despite the good-natured rebuke, the indications were precise, starting from the initial frame in which Ornella Muti, in Il viaggio di Capitan Fracassa (The Voyage of Captain Fracassa, 1990), talks about the inexorable pace of time and the cyclic return of things. The theme of history, in fact, covers every possible discourse on Scolas cinema: the motif of nostalgia, the analysis of history and microhistory, the reflection on the relationship between history and film history, the reconstruction of the committed and militant filmmaker. In his films, la Storia (History) is found in the style of politics, but also in space, in the closed or open places that make the great scenography of History. History is a fundamental protagonistHistory with a capital H and also history and histories (storie) with a lowercase h. Here, I am not only referring to the histoire de longue dure (history of long duration or the study of long-term historical structures), to use Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvres phrase, and to the histoire vnementielle

Next page