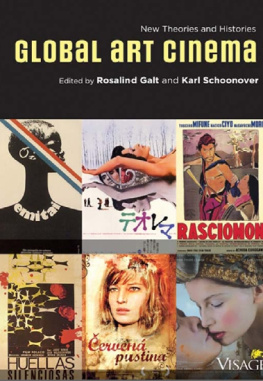

Edited by

Rosalind Gal t Karl Schoonove r

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that furthe r Oxford Universitys objective of excellenc e in research, scholarship, and education .

Oxford New Yor k Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karach i Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairob i New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toront o

With offices i n Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greec e Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapor e South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietna m

Copyright 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc . 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 1001

www.oup.co m

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Pres s

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced , stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means , electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise , without the prior permission of Oxford University Press .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Dat a

Global art cinema : new theories and histories / edited by Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover . p. cm . Includes bibliographical references and index . ISBN 978-0-19-538562-5; 978-0-19-538563-2 (pbk. ) 1. Motion picturesAesthetics. 2. Independent filmmakers . I. Galt, Rosalind. II. Schoonover, Karl . PN1995.G543 201 791.4301dc22 200902610

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Foreword

Dudley Andrew

I never apologize for combining the word art with the word cinema. You would need a nineteenth-century conception of arta clich even thento cast it as effete. After Freud, Trotsky, Benjamin, and Adorno, after futurism, constructivism, dada, surrealism, and the explosion of pop, it seems hard to remember that artand the art filmwas once considered the spiritual playground or retreat of a bourgeois elite. True, there had been Film dArt around 1910, best remembered for the black-tie audience assembled for the premiere of LAssassinat du duc de Guise at the Paris Opra with music composed by Saint-Saens. And in the 1920s certain patrons of The Seventh Art treated cinema as though it were a debutante being intro duced into high society. In Film as Art ( Film als Kunst , 1932) Rudolf Arnheim consolidated the aesthetic principles achieved toward the end of the silent era, principles based on classical painting (balance, emphasis, discretion, and so forth). But Duchamp, Leger, and Buuel had already blustered in to spoil the ball.

W hen cinema next attached itself to art, after the Second World War, it was not to emulate the forms and functions of painting or drama, but to adopt the intensity of their creation and experience. For even when it is seemingly ready-made, trouv, informe, or absurd, art is exigent in the demands it makes on makers and viewers. Art cinema is ambitious, the word with which Franois Truffaut characterized the filmmakers he championed, the film maker he wanted to become. If cineastes are artists, it is because they partake of the ambition of genuine novelists, painters, and sculptors to supersede the norm, each in his own domain.

I n 1972 Victor Perkins answered Film as Art with his own Film as Film . We loved this title. It demonstrated that cinema had arrived, had come into its own and no longer needed the corroboration of established aesthetics to be taken seriously. A terrific book, it pointed to the most telling and complex moments within a spectrum of films from Hollywood genre pieces to silent classics. As his title announced, Perkins oriented us to experience and to explore films on their own terms. He adjusted his rhetoric so as to enter not so much the discourse as the world projected before him. You can argue that art cinema, like art in general, serves contradictory functions (as cultural capitalindeed as actual capitalas propaganda or cri tique of ideology, as mass entertainment, etc); but those who live their lives in tandem with cinema care precisely about the function of film as film, even while understanding it to be congenitally impureas Bazin insistedand enmeshed in the terrestrial and the social.

Global Art Cinema : the first adjective of this title binds what it mod ifies to a mesh of relations that keep the whole thing from floating up and away like a balloon. At the same time Art Cinema is by defini tion pan-national, following the urge of every ambitious film to take off from its point of release, so as to encounter other viewers, and other movies, elsewhere and later. The title in fact begs a question debated in comparative literature over the vexed term, dating from Goethe, of Weltliteratur . For David Damrosch, a text joins the com munity of world literature when it finds sustained reception beyond the borders of the specific community out of which it arose. World literature comprises not just a huge bibliography of works, but more pertinently the complex interactions among these works, as they form the mixed traditions absorbed by later writers, as they are consumed by various communities of readers, and as they are tracked and interpreted by scholars and academics. Perched on the promontories of their carefully erected theories, scholars have been tempted to sense intelligent design in the evolution of world literature. On behalf of literature they take note of contributions that come from unlikely quarters where new topics, new techniques, and new generic hybrids stretch language across more and more realms and types of experience. As for the rest of writing (all those newspaper essays and serial stories that are thrown away, those folktales never leaving the local language, that doggerel whose echoes remain in homes and cafs), is this not material for the anthropologist more than the literary scholar? Such materials give insights into what is valued by individuals and groups, but, if never translated, these texts interact not at all with readers outside the community. Goethe and Damrosch would leave them alone, and so does global art cinema.

N o one would dispute the value of the visual culture of any given time or place, or even the beauty of some of its expressions; no one would doubt the artistry, intelligence, and wit that has gone into in numerable state-commissioned documentaries, popular television shows, advertisements, home movies, and episodes of local film series. But insofar as these remain within the culture, discovered per haps by scholars interested in those cultures, they do not participate in the cultural economy of world film and certainly do not belong to anything one would label global art cinema.

T he latter might best be thought of as festival fare, since today every film programmed by an international festival becomes de facto visible to spectators anywhere on the globe who seek out distinctive movies. In the early days of festivals, titles were selected by national commissions to go abroad, whereas today festivals select what they show, sometimes even commissioning work by artists they deem tal ented. This does not upset the rapport of national culture to the cul ture of the cinephile, but it accelerates its movement. For example, of the hundred films made each year in the Philippines this past decade, only fifteen or so can be identified as part of the Philippine art ci nema, specifically those that have been selected to be screened abroad. Whereas it took the Taiwanese new wave several years to penetrate the international market, the Philippine titles in todays global net work have instantly left their imprint, altering the profile of Asian cinema in toto. So there would seem to be two distinct Philippine cinemas, one belonging to a specific culture bound principally by the Tagalog language, and the other taken up by a polyglot international audience who can access these films at festivals or download them on their computers.