Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2017 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-8047-9891-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-5036-0070-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-5036-0075-1 (electronic)

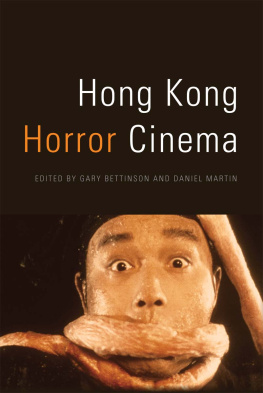

Cover image: Film still from Back Yard Adventures (1955), a Cantonese remake of Hitchcocks Rear Window.

Typeset by Motto Publishing Services in 10/14 Palatino

ARRESTING CINEMA

SURVEILLANCE IN HONG KONG FILM

KAREN FANG

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

For Elliot and Benjamin (my best work)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

From Rear Window, Modern Times, and Man with a Movie Camera, to Blow-Up, The Conversation, and The Truman Show, some of world cinemas best-known and most critically acclaimed films are about surveillance. Surveillance films extend over a wide range of genres and include movies as diverse as The Matrix, The Lives of Others, Cach, and even low-budget, pulpy films like the Paranormal Activity horror franchise or breakthrough independent films like sex, lies, and videotape. One of the main things that these films have in common is that they usually portray social, spatial, and data monitoring as intrusive, perverse, repressive, and violent. This critical and highly suspicious view of surveillance has only consolidated as a result of digital technology and the highly contested debates about security and civil liberties in the post-9/11 world. Well into the twenty-first century, controversies regarding data mining, biometrics, mandatory ID cards, and other technologies and practices have caused modern society to grow more cautious about the varied and pervasive forms that subject us to surveillance. Within this context, cinematic representation can function as a compelling mirror of the ubiquitous instances of screen- and camera-mediated monitoring by which many of us live our daily lives.

Arresting Cinema adds to this extensive critical and popular dialogue by exploring Hong Kong film both as a necessary contribution to an otherwise predominantly Western-centered discourse and as the source of a unique view of surveillance ethics and aesthetics. Hong Kong cinema has been long known for its prolific production and enviable local and regional success; during its height in the mid-1970s through the early 1990s, the industry exported films throughout Asia, and the market was almost unique in that its consumption of locally made product exceeded that of Hollywood imports. But Hong Kong cinema should also be noted for its intelligent and often unexpected take on world films important surveillance themes. In Hong Kong film, surveillance themes can surface in unique and unconventional genres, such as gambling and comedy, and often in contexts that depict those themes with a tolerance or enthusiasm unprecedented in Hollywood-dominated treatments. Yet, rather than dismiss these differences between Hong Kong and Hollywood cinema as symptomatic of essential and orientalist differences between East and West, we should take a closer look at the territorys history, especially the cinemas acumen at blending imported Hollywood conventions with Chinese cultural traditions, which demonstrate Hong Kongs direct engagement with global surveillance culture. As shown by recent high-profile events, such as the 2014 Umbrella protests by local democratic activists and the temporary stay in Hong Kong the preceding year of American domestic spying whistleblower Edward Snowden, Hong Kong has long fostered a complex tradition of surveillance critique whose history, while idiosyncratic, nevertheless has great relevance for the world at large.

This book is guided by two overarching themes. One is the relationship of surveillance to spectacle, not only the way that cinematic images engage surveillance theory and practice but also the disparate concepts and aesthetics that surveillance and spectacle imply. Although much of the recent scholarship on surveillance imagery in cinema tends to characterize these terms as related, this was not always the case. Michel Foucault, for example, famously opposes surveillance to spectacle in Discipline and Punish, and Laura Mulvey, in her equally seminal essay Visual Pleasure and the Narrative Cinema, sketches a similar opposition, contrasting a Hitchcockian cinema of narrative investigation with a Sternbergian aesthetic in which image trumps all. Yet Hong Kong film, with its inveterate surveillance plots and imagery knitted into kinetic action and its famously eye-popping film id Indeed, with regard to the film medium in particular, Hong Kongs dynamic cinema traditions present a rich and intriguing archive to contrast with the spectacular surveillance traditions widely noted in Western film.

This formal interest in surveillance spectacle also relates to my second overarching theme: Hong Kong films challenge to Chinese soft power. Originally coined to conceptualize American foreign policy after the Cold War, soft power is now a major topic in studies of Chinese and Sinophone film and culture, which since the mid-2000s have used the term to describe Chinas aspirations to the global influence once associated with American hegemony. Surveillance has always been an implicit factor in soft power, given the concepts Cold War origins and especially its current revival with Chinese ascendancy, but when realized in film, the issue of soft power further underscores the aesthetic and thematic differences between Hong Kong images of surveillance and more overtly spectacular cinema emanating from Chinas surveillance state. Thus, while cinematic manifestations of Chinese soft power can be found in the recent revival of traditional wuxia martial arts films; the crowd-pleasing blockbuster films of Feng Xiaogang, the Chinese Spielberg; or even Zhang Yimous orchestration of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, this books focus on Hong Kong film reveals an alternative aesthetic. This aesthetics unique treatment of surveillance behaviors contrasts with the hard political intent behind Chinese soft power. Its comparative subtlety and occasionally subversive undertones pose an alternative mode of Sinophone soft power that paradoxically emanates from a position of political disempowerment.

Like many fans of Hong Kong film, my love for the city is almost impossible to disentangle from my fascination with its cinema, but given my interest in surveillance, this popular conflation of city with cinema is particularly justified by the centrality of screen and camera mediation in both entities. No one who visits or lives in Hong Kong can fail to recognize the ubiquitous closed-circuit television (CCTV) monitors and security cameras throughout the city, imparting an inevitable familiarity to the sense of seeing the cityand oneselfon-screen. Yet, as this book shows, this explicitly cinematic surveillance imagery is but the tip of the iceberg in a massive official and de facto surveillance complex that includes the territorys omnipresent private watchmen and security guards, unusually strong regulations and informal practices regarding human monitoring, a wealthy and remarkably powerful municipal government, and one of the worlds largest and most empowered urban police forces. Local cinema mirrors these structural attributes in some of the genres most commonly identified with Hong Kong film, but what is particularly intriguing about both Hong Kong cinema and the city itself is that they have fostered those developments to the point that they exist largely unremarked. Thus, while it is common for London to be described as the most surveilled city in the world, Hong Kong provides an important counter and comparison to that claim. If the assertive and tellingly awed tones by which London is described betray a perverse kind of pride, Hong Kongs equally extensive surveillance society deserves similar noticeand is all the more intriguing because it has developed almost without notice.

Next page