RADIOACTIVE!

How Irne Curie & Lise Meitner Revolutionized Science and Changed the World

WINIFRED CONKLING

ALGONQUIN YOUNG READERS

2016

CONTENTS

A WORD ABOUT NAMES

This is the story of Lise Meitner and Irne Curie, but it also covers events in the lives of other members of the Curie family, including Marie Curie, Pierre Curie, Eve Curie, and Frdric Joliot-Curie. To make matters more confusing, as a married woman Irne sometimes used the name Curie and other times Joliot-Curie. While it is customary to refer to a subject by last name on second and sub-sequent references, in the text the Curies are referred to by their first names if there is any possibility of confusion. The use of first names is intended to promote clarity; it is never meant to minimize status or respect.

1

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL EXPERIMENT IN THE WORLD

T heir moment had finally arrived. In the fall of 1933, scientists Irne and Frdric Joliot-Curie were invited to present their latest research at the 7th Solvay Conference in Brussels, Belgium. The French researchers were thrilled to have a chance to appear before their intellectual idols, 40 of the best and brightest nuclear physicists in the world, and impress them with their insights into the structure and properties of the atom and how it worked.

The Joliot-Curies were among the youngest scientists at the conference: Irne was 36 years old and Frdric was 33. As a research team they had earned a reputation for doing interesting work in the past few years, but this promised to be their breakout moment; their chance to step out from the shadow cast by Irnes parents, Nobel Prizewinning scientists Marie and Pierre Curie. Marie had attended this conference every year, but this was the first time that Irne and Frdric had been invited.

Frdric almost always came across as poised and confident, but when it was his turn to stand behind the podium he was noticeably nervous. Most of the men in attendance had fashionable mustaches or beards; Frdrics clean-shaven face made him appear even younger than he was. Irne stood by Frdric as he presented their research findings, which suggested a new way of thinking about the architecture of the atom.

Forty of the worlds leading physicists attended the 7th Solvay Conference in Brussels, Belgium, in October 1933. Irne Joliot-Curie is seated in the front row, second from the left. Lise Meitner is in the front row, second from the right. Marie Curie is seated in the first row, fifth from the left. Frdric Joliot-Curie is standing in the second row, third from the left.

Physicists at the turn of the 20th century were just beginning to understand atomic structure. We now know that atomsthe basic building blocks of matterconsist of a core called a nucleus, which is made up of particles called protons (with a positive charge) and neutrons (with no charge), and that the nucleus is circled by electrons (with a negative charge). While this information is considered elementary today, scientists were just figuring it out in the 1930s.

At the time the Joliot-Curies were presenting their research, physicists thought that the nucleus of the atom consisted of protons and electrons, positive and negative particles. In the 1930s, atomic structure was uncharted territory for even the most brilliant physicists. Nobel Prize winning physicist Wolfgang Pauli explained the state of knowledge when he said, , and for me it is so difficult that I wish I were a film comedian or something like that and had never heard of physics in the first place.

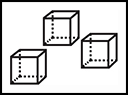

A (VERY) BRIEF HISTORY OF ATOMIC STRUCTURE

Ancient Greek philosopher Democritus (460370 bc ) proposed the theory that everything in the universe is made up of tiny, indivisible, indestructible particles known as atoms.

John Dalton (17661844) suggested that atoms could combine to form compounds. He envisioned atoms as solid spheres.

Joseph John Thomson (18561940) discovered negatively charged electrons. He developed the plum pudding model of the atom in which a large, positively charged mass (the plum pudding) contains a number of randomly dispersed negatively charged small electrons (the raisins in the pudding). A more modern model would be chocolate chips in a cookie or blueberries in a muffin.

Ernest Rutherford (18711937) changed the understanding of atomic structure in 1911. He conducted an experiment in which he fired electrons through a sheet of gold foil. Most of the electrons passed straight through, but a few were deflected, or knocked out of alignment. From that, Rutherford determined that most of the mass of a gold atom was concentrated in a central nucleus which was surrounded by electrons.

Niels Bohr (18851962) argued that electrons revolved around the nucleus in fixed orbits, much like planets rotating around the sun. His model included a nucleus made up of protons and neutrons.

The modern model, sometimes called the electron cloud model, refines Bohrs model by acknowledging that its impossible to know the exact position or speed of an electron at any one moment. Instead of fixed electron shells, this model shows electrons as inhabiting a cloud, which indicates the probable position of an electron rather than a firm boundary. This model takes into account the complex and erratic behavior of electrons.

The research that Irne and Frdric presented at the Solvay Conference challenged what was believed about atomic structure at that time. When the Joliot-Curies presented their findings about neutrons, the scientists in the room were not convinced. Instead of giving the praise Irne and Frdric had hoped for, their colleagues questioned their results. British physicist Patrick Blackett challenged the Joliot-Curies interpretation of their research. As Irne took the floor and tried to defend their findings, the audience whispered to one another and remained dubious.

Then Lise Meitner, a German scientist with an impeccable reputation, raised her hand.

The room quieted. The chairman called on her, and Meitner stood and said: . We have been unable to uncover a single neutron. She then sat down.

Next page