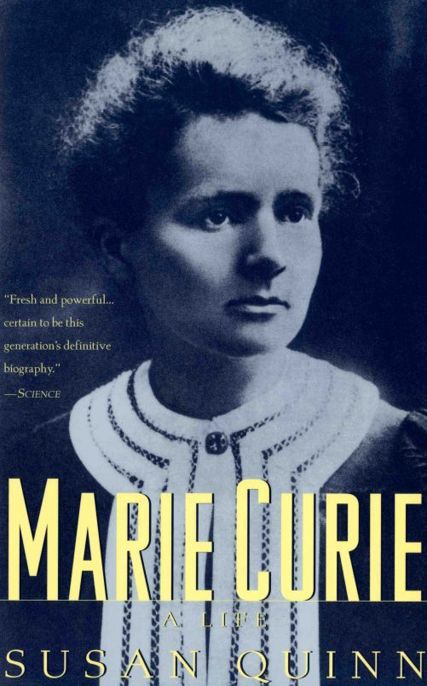

Marie Curie: A Life

by Susan Quinn

Published by Plunkett Lake Press, August 2011

www.plunkettlakepress.com

Susan Quinn

Notes for this book can be found in the hardcover and paperback editions.

TO DANNY

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. A Family with Convictions

2. A Double Life

3. Some Very Hard Days

4. A Precious Sense of Liberty

5. A Beautiful Thing

6. Everything Hoped For

7. Discovery

8. A Theory of Matter

9. The Prize

10. Turning Toward Home

11. Desolation and Despair

12. A New Alchemy

13. Rejection

14. Scandal

15. Recovery

16. Serving France

17. America

18. A Thousand Bonds

19. Legacies

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

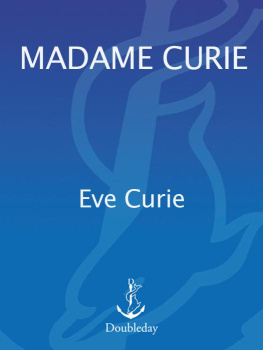

Marie Curie came from a family of chroniclers. Her father, Wadysaw Skodowski, wrote a history of his family in Poland, and her brother Jzef recapitulated the story, adding an account of his generation. Maries sister Helena also wrote her memoirs and published them in Polish. Marie herself wrote a biography of Pierre Curie and a brief autobiography. In addition, both of Marie Curies children wrote about their famous mother. In 1937, her younger daughter ve Curie published one of the most popular biographies of all time, Madame Curie.

Like all family historians, these members of the Skodowski-Curie clan had their reasons for setting down the story. For Maries father, and to a large extent for her brother Jzef, keeping a family history was a political act, a means of preserving the precious Polish heritage which foreign oppressors made such brutal attempts to blot out during most of their lifetimes. For Maries sister Helena and daughter Irene, it was a matter of elaborating one aspect of the story.

But in the case of both Marie Curie and her daughter ve, one important reason for writing was unspoken. For Marie Curie, writing a biography of Pierre Curie was an act of love, a part of the religion of memories she practiced after his tragic, premature death. Her autobiography, written in English and never translated for fear the French would find it immodest, was a means of thanking her American admirers, who had been so generous. But it also provided the outlines for the triumphal version of her life that her daughter would write soon after she died.

After spending seven years working on this biography, I am more astounded than ever at the speed with which ve Curie was able to gather the facts and put together her mothers story in Madame Curie. Her biography of her mother appeared in 1937, three years after Marie Curies death. When I asked ve Curie Labouisse, in an interview in 1988, why she wrote the book so quickly, she told me that she was afraid that someone else would do it first and not get it right.

For ve Curie, getting it right meant portraying her mother as a woman of great nobility, tremendously hardworking and dedicated, who often didnt get the credit she deserved. She tells the story so well that it is not immediately obvious that the biography is serving as a defense of her mother. And yet lurking beneath the surface and motivating the undertaking is an event which had had a devastating effect on Marie Curie: her public exposure and vilification because of an affair she had with a fellow scientist, Paul Langevin. Although Marie Curie was a widow at the time, Paul Langevin was married and the father of four children. And reactionary elements in the French press used the incident to drum up xenophobic hatred of the foreign woman who was destroying a French home, and to exploit an array of prejudices against godless intellectuals and emancipated women. It was partly to prevent the retelling of that painful episode that ve Curie wrote her book, which deals with it in a few paragraphs as a perfidious campaign... against this woman of forty-four, fragile, worn out by crushing toil, alone and without defense.

My reasons for undertaking a biography of Marie Curie were as much of our time as ve Curies were of hers. I wanted to peel back the layers of myth and idealization which had grown up around Marie Curies story since her daughter told it over fifty years ago. I have looked for evidence that Marie Curie was not just a singular, exceptional woman (though she was indeed that) but also a woman who experienced the same difficulties as other women with strong opinions and ambitions. That meant exploring more carefully the barriers to women which surrounded her in Poland and in France. It also meant looking more closely at her defeats and humiliations at the hands of the Academy of Sciences as well as the proper bourgeoisie and the outrageous right-wing press.

The triumphal version of Marie Curies life tends to portray her as impervious to these defeats and humiliations. Of her rejection from the Academy of Sciences, for instance, ve Curie wrote, She was not to comment by so much as a word upon this setback which in no wise afflicted her. This is undoubtedly what Marie Curie herself said about her exclusion from the most important scientific institution in France at the time. But the evidence suggests that the rejection had a profound effect: for many years afterward she did not publish her work in the Comptes rendus, the official organ of the Academy and the most widely read French scientific publication.

Throughout her life, and particularly after she became the focus of attacks and adulation, Marie Curie tended to present a cool facade to the world. Einstein, though he was fond of her, once went so far as to say that Marie Curie was poor when it comes to the art of joy and pain. In fact just the opposite was true.

Several important new sources have provided evidence of Marie Curies intense emotional life. In 1990, a journal that Marie Curie kept during the year after Pierres death was made available for the first time to researchers at the Bibliothque nationale in Paris; her entries, addressed to her lost husband, reveal her to be a woman capable of profound joy and deep sorrow.

At the cole de physique et chimie in Paris, I found evidence of Marie Curies passionate attachment to those she cared about. In testimonials which had been closed until I read them, Marie Curies friends told the story, in detail, of her affair with Paul Langevin and of the scandal that ensued. One friend described her as capable of going through fire for those she loved. In the Langevin affair, she certainly did. In the end the story reveals Marie Curie as someone who, like the rest of us, didnt always make the wisest choices in love.

The idealization of Marie Curie the scientist has gone in the opposite direction. In general she has been portrayed as passionate, hardworking, dedicated, and a seeker of a cure for cancer. She herself, when she described her work in discovering and then isolating radium, emphasized the dedication and hard physical toil rather than the important scientific ideas upon which the work was premised. But in retrospect, her labor and her association with the search for a cancer cure were far less important than her critical insight that radioactivity was an atomic property of her newly discovered elements. It was this idea, put forth almost one hundred years ago, which led to our modern understanding of the structure of the atom. Just as my biography provides new evidence of the range of emotions Marie Curie experienced in her personal life, it also demonstrates, through a detailed examination of her discovery of radioactivity, that her success as a scientist depended not just on her dedication but also on her intellectual clarity.

The distinction between her personal and scientific life was one Marie Curie made during one of her bravest hours. At the height of the Langevin scandal, after it was announced that she had won the Nobel Prize for chemistry, a member of the Swedish Academy wrote to tell her that she would not be welcome in Sweden, because of the Langevin affair, and should refuse the prize until she had cleared her name. Marie Curie wrote back that, in fact, the prize had been awarded for her discovery of radium and polonium and she intended to come to Sweden to accept it. I believe that there is no connection between my scientific work and... private life.

Next page