MARIE CURIE

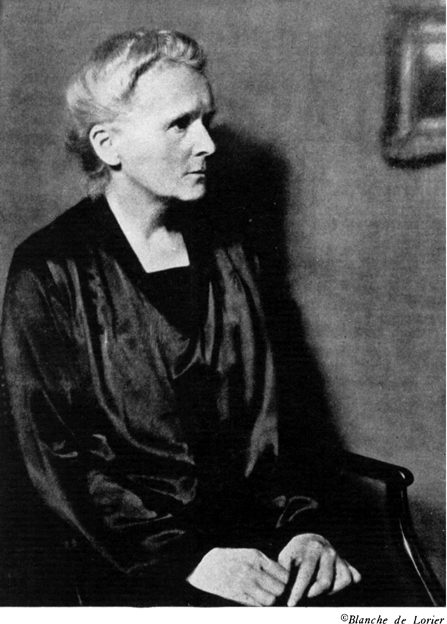

A Portrait Made in 1929.

COPYRIGHT , 1937

BY DOUBLEDAY, DORAN & COMPANY, INC .

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CL

eISBN: 978-0-307-81912-3

v3.1

Contents

Illustrations

Mme Sklodovska, Marie Curies Mother

The Sklodovski Children

The House in Which Marie Curie, then Manya Sklodovska, Taught as a Governess

M. Sklodovski and His Three Daughters

The Two Positivists

The Diploma of the Second Nobel Prize Award Made to Mme Curie in 1911

A Page from Manya Sklodovskas Private Notebook, Written in 1885

The Curie Family

Pierre Curie, as He Appeared Lecturing to His Classes in 1906

Two Views of the Shed at the School of Physics on the Rue Lhomond Where Radium Was Discovered

Pages from Marie Curies Work Books, 18971898

Henri Becquerel, the First Scientist to Observe the Phenomenon of Radioactivity

Marie and Pierre Curie with Their Daughter, Irne, in 1904

Marie Curie and Her Two Daughters, Eve and Irne, in 1908

Marie Curie and Pierre Curie and Their Daughter, Irne, in the Garden of the House on Boulevard Kellermann, 1904

Marie Curie in Her Laboratory, 1912

Marie Curie with Her Two Sisters, Mme Szalay and Mme Dluska, and Her Brother M. Sklodovski, Photographed in Warsaw in 1912

Mme Curie in Her Laboratory, in 1912

Marie Curie at the Wheel of the Famous Renault Car Converted into a Radiological Unit

Marie Curies Favorite Portrait of Her Husband

The Radium Institute at Warsaw

The Radium Institute at Paris

Mme Curie, Irne Curie and Pupils from the American Expeditionary Corps, at the Institute of Radium in Paris

Marie Curie with Dean Pegram, Dean of the School of Engineering at Columbia University, 1921

Marie Curie Discussing a Scientific Problem at Pittsburgh During Her American Tour

Marie Curie and President Harding During Her Tour of the United States in 1921

Mme Curie in Her Office at the Radium Institute in Paris, 1925

A Group Photograph Made at the Institute of Radium in Paris

Mme Curie and Her Daughter, Irne, 1925

Marie Curie in 1931, Three Years before Her Death

The Curie Family Tomb, in the Cemetery at Sceaux

Introduction

T HE LIFE OF MARIE CURIE contains prodigies in such number that one would like to tell her story like a legend.

She was a woman; she belonged to an oppressed nation; she was poor; she was beautiful. A powerful vocation summoned her from her motherland, Poland, to study in Paris, where she lived through years of poverty and solitude. There she met a man whose genius was akin to hers. She married him; their happiness was unique. By the most desperate and arid effort they discovered a magic element, radium. This discovery not only gave birth to a new science and a new philosophy: it provided mankind with the means of treating a dreadful disease.

At the moment when the fame of the two scientists and benefactors was spreading through the world, grief overtook Marie: her husband, her wonderful companion, was taken from her by death in an instant. But in spite of distress and physical illness, she continued alone the work that had been begun with him and brilliantly developed the science they had created together.

The rest of her life resolves itself into a kind of perpetual giving. To the war wounded she gave her devotion and her health. Later on she gave her advice, her wisdom and all the hours of her time to her pupils, to future scientists who came to her from all parts of the world.

When her mission was accomplished she died exhausted, having refused wealth and endured her honors with indifference.

It would have been a crime to add the slightest ornament to this story, so like a myth. I have not related a single anecdote of which I am not sure. I have not deformed a single essential phrase or so much as invented the color of a dress. The facts are as stated; the quoted words were actually pronounced.

I am indebted to my Polish family, charming and cultivated, and above all to my mothers eldest sister, Mme Dluska, who was her dearest friend, for precious letters and direct evidence on the youth of the scientist. From the personal papers and short biographical notes left by Marie Curie, from innumerable official documents, the narratives and letters of French and Polish friends whom I cannot thank enough, and from the recollections of my sister Irne Joliot-Curie, of my brother-in-law, Frederic Joliot, and my own, I have been able to evoke her more recent years.

I hope that the reader may constantly feel, across the ephemeral movement of one existence, what in Marie Curie was even more rare than her work or her life: the immovable structure of a character; the stubborn effort of an intelligence; the free immolation of a being that could give all and take nothing, could even receive nothing; and above all the quality of a soul in which neither fame nor adversity could change the exceptional purity.

Because she had that soul, without the slightest sacrifice Marie Curie rejected money, comfort and the thousand advantages that genuinely great men may obtain from immense fame. She suffered from the part the world wished her to play; her nature was so susceptible and exacting that among all the attitudes suggested by fame she could choose none: neither familiarity nor mechanical friendliness, deliberate austerity nor showy modesty.

She did not know how to be famous.

My mother was thirty-seven years old when I was born. When I was big enough to know her well, she was already an agingwoman who had passed the summit of renown. And yet it is the celebrated scientist who is strangest to meprobably because the idea that she was a celebrated scientist did not occupy the mind of Marie Curie. It seems to me, rather, that I have always lived near the poor student, haunted by dreams, who was Marya Sklodovska long before I came into the world.

And to this young girl Marie Curie still bore a resemblance on the day of her death. A hard and long and dazzling career had not succeeded in making her greater or less, in sanctifying or debasing her. She was on that last day just as gentle, stubborn, timid and curious about all things as in the days of her obscure beginnings.

It was impossible to inflict on her, without sacrilege, the pompous obsequies which governments give their great men. In a country graveyard, among summer flowers, she had the simplest and quietest burial, as if the life just ended had been like that of a thousand others.

I should have liked the gifts of a writer to tell of this eternal studentof whom Einstein said: Marie Curie is, of all celebrated beings, the only one whom fame has not corruptedpassing like a stranger across her own life, intact, natural and very nearly unaware of her astonishing destiny.

E VE C URIE .

T HE AUTHOR is indebted to Dr Harry Plotz, of the Pasteur Institute, for his assistance in checking certain of the scientific material in this book.

PART ONE