W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

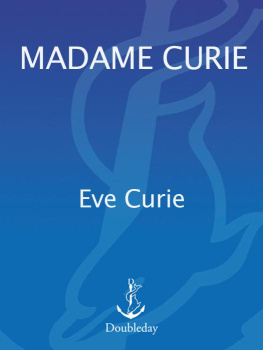

Acknowledgment is made to quote material from Madame Curie by Eve Curie, translated by Vincent Sheean, copyright 1937 by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. Used by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Introduction

P aris, April 20, 1995: the white carpet stretched block after block down the rue Soufflot ending in front of the Panthon, which was draped in tricolor banners that extended from the dome to the pavement. To the tune of the Marseillaise, the Republican Guardsmen moved along the white expanse. The thousands who lined the streets were unusually quiet; some tossed flowers as the cortge moved by. Faculty from the Curie Institute were followed by Parisian high school students who held aloft four-foot blue, white, and red lettersthe Greek symbols for alpha, beta, and gamma rays.

As the marchers approached the Panthon, they fanned out and stared up at a platform under the grand dome on which were seated such luminaries as President Franois Mitterrand. Suffering from cancer, in the last weeks of his fourteen-year presidency, he had decided to dedicate his final speech to the women of France and in a dramatic gesture to place the ashes of Madame Curie and her husband, Pierre, in the Panthon, thus making Marie (Marya Salomee Sklodowska) Curie the first woman to be buried there for her own accomplishments. The Curies had been exhumed from their graves in the suburb of Sceaux to join such French immortals as Honor-Gabriel Riqueti (Comte de Mirabeau), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, mile Zola, Victor Hugo, Voltaire (Franois-Marie Arouet), Jean-Baptiste Perrin, and Paul Langevin.

Seated beside Mitterrand was Lech Walesa, the president of Poland, Madame Curies native country. Finally, there were the families of the two scientists being enshrined: their daughter Eve, and the children of their deceased daughter Irne and her husband Frdric Joliot-CurieHlne Langevin-Joliot and Pierre Joliot, both distinguished scientists.

Pierre-Gilles de Gennesthe director of the School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry of the City of Paris (EPCI), where Marie and Pierre had discovered radioactivity, radium, and poloniumspoke first, saying that the Curies represented the collective memory of the people of France and the beauty of self-sacrifice. Lech Walesa spoke of Marie Curies Polish origins and termed her a patriot both of Poland and France. Franois Mitterrand then rose:

This transfer of Pierre and Marie Curies ashes to our most sacred sanctuary is not only an act of remembrance, but also an act in which France affirms her faith in science, in research, and we affirm our respect for those whom we consecrate here, their force and their lives. Todays ceremony is a deliberate outreach on our part from the Panthon to the first lady of our honored history. It is another symbol that captures the attention of our nation and the exemplary struggle of a woman who decided to impose her abilities in a society where abilities, intellectual exploration, and public responsibility were reserved for men.

Above Mitterrands head, as he spoke these words, one could read the inscription on the Panthons faade: TO GREAT MEN FROM A GRATEFUL COUNTRY. The irony is apparent.

After the speeches, a deafening ovation echoed down the streets. The modest Pierre Curie, who wanted to be buried in Sceaux because he abhorred noise and ceremonies, would have hated this display. But, like it or not, the Curies, especially Marie, had been deified. Madame Curie was now an icon for the ages and an inspiration to women who saw in her the fulfillment of their own dreams and aspirations, however vague. I was among them.

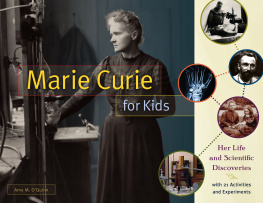

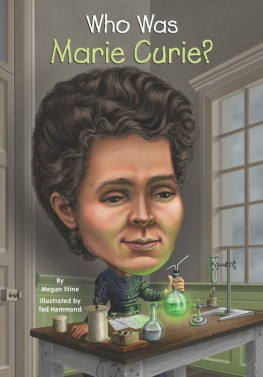

As a teenager, I tacked up, among the detritus on my bulletin board, between a reproduction of Van Goghs Starry Night and my Friday night bowling card, a photograph of Marie Curie sitting under an elm tree, her arms stretched out to encircle the waists of her daughters, two year old Eve, and nine year old Irne. I dont know why I was drawn to this photograph, but it wasnt about science. Madame Curie was my idol, and like other idols you dont have to know what they did to worship them. Perhaps I found comfort in what I took to be Maries protective embrace since, at the time, my own mother was far away in a hospital, having been critically injured in an automobile accident. Who knows?

In the photograph there are none of the usual smiling faces. All three look ineffably sad. I didnt know why then. Now I do. Under the picture I had placed two of Madame Curies quotations: Nothing in life is to be feared. It is only to be understood, and It is important to make a dream of life and of a dream reality. It was only while researching this book that I found that Pierre Curie, not Marie, wrote the latter.

Marie with Eve (left) and Irne (right) in the garden at Sceaux in 1908.