Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CW17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

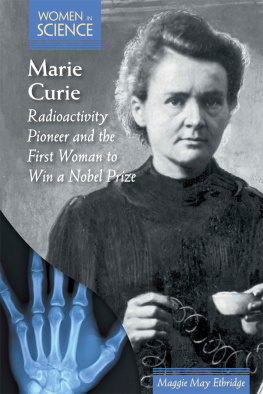

Names: Ethridge, Maggie May.

Title: Marie Curie : radioactivity pioneer and first woman to win a Nobel Prize / Maggie May Ethridge.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, [2017]

| Series: Women in science | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016023217 (print) | LCCN 2016024757 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502623096 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502623102 (E-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Curie, Marie, 1867-1934. | Women chemists--Poland--Biography. | Women chemists--France--Biography. | Nobel Prize winners--Biography.

Classification: LCC QD22.C8 E84 2017 (print) | LCC QD22.C8 (ebook) | DDC 540.92 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016023217

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editors: Leah Tallon/Kristen Susienka

Copy Editor: Rebecca Rohan

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Alan Sliwinski

Production Assistant: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover ullstein bild/Getty Images; itsmejust/Shutterstock.com; Throughout book Bereziuk/Shutterstock.com; p. 4, 56, 95 Popperfoto/Getty Images; p. 8 File:Marie Sklodowska 16 years old.jpg/Wikimedia Commons; p. 11, 40, 48, 62, 78 Photos.com/Thinkstock; p. 13, 101 Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 15 ullstein bild/Getty Images; p. 17 AFP/Getty Images; p. 18 Photo Researchers/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 27 Heritage Images/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 31 Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images; p. 36 Library of Congress; p. 38 Laurent Erny/Bridgeman Images; p. 44, 99 Bettmann/ Getty Images; p. 46 Photo Researchers/Science Source/Getty Images; p. 60 American Institute of Physics/Science Photo Library/Getty Images; p. 66 Boyer/Roger Viollet/Getty Images; p. 69, 86 Print Collector/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 76 Look and Learn/Bridgeman Images; p. 82 Universal Images Group/Universal History Archive/Getty Images; p. 96 Zhang Fan/Xinhua/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 104 Joachim Hiltmann/imageBROKER/Getty Images.

Printed in the United States of America

Marie Curie as a young girl in Poland

INTRODUCTION

THE LIFE OF MARIE SKLODOWSKI CURIE

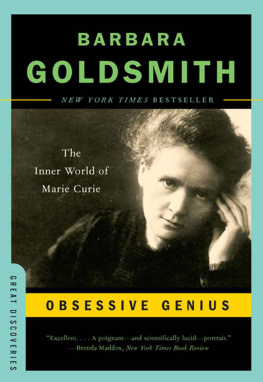

M arie Sklodowski Curie is one of the most important scientists in human history. Born November 7, 1867 to a poor but loving Polish family, she brought a deep intellect and ethics of hard work to her time of higher learning at the Sorbonne in Paris, France. At the Sorbonne, she met her husband, Pierre Curie. The Curies eventually had two daughters, Irne and ve. Pierre was an important scientist, and the two married and began working together on Maries thesis. Her thesis was built on the work of Wilhelm Rntgen and Antoine Henri Becquerel, two physicists. Curie herself was a chemist and physicist.

In July 1898, the Curies announced to the Academy of Sciences the discovery of a new chemical element, polonium. At the end of the year, another paper was presented to the Academy, announcing the discovery of another element, called radium. The Curies and their colleague, Henri Becquerel, were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903 for their research on the phenomenon of radiation. The Curies had discovered the source of radiation, and proven that it came from the atomic level, which completely changed the scientific understanding of the atom.

Pierre Curies life ended in 1906 after he was tragically knocked down and killed by a horse-drawn carriage. Soon afterward, Marie Curie took over his post as professor of general physics in the Faculty of Science, as the first woman to teach at the Sorbonne. She ensured the creation of The Radium Institute, of which she was also appointed director of the Curie laboratory. The Curie Foundation was established in 1920 and was quickly recognized as a public interest institution the following year, becoming a model for cancer centers around the world. In 1970, The Radium Institute and the Curie Foundation merged to become Institut Curie, with three missions of research, teaching, and treating cancer.

In 1911, Curie received a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her discovery of the elements polonium and radium. The discovery of radium led to some of the most important treatments of cancer. Radium has the ability to kill cells, so it is used for targeted elimination of cancer cells. Radium is also used in dating techniques on ancient objects, rocks, and the age of our universe, as well as for molecular biology and modern genetics. Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, and she remains the only woman to win the award in two different fields.

The Curies research was a crucial step in the development of surgical X-rays. During World War I, Curie designed ambulances equipped with unique X-ray equipment. Curie herself drove these vehicles on the front lines. The International Red Cross assigned her as head of radiological service, and injured soldiers in battlefield tents were assisted by her Little Curies, the portable X-ray machines she had invented. Curie held training courses for medical orderlies and doctors so they could quickly absorb the new techniques, and she taught these techniques at The Radium Institute after the war.

By the late 1920s, her health was beginning to deteriorate from exposure to radiation. She died on July 4, 1934 from aplastic anemia, a disease of the bone marrow. The Curies eldest daughter, Irne, was also a scientist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Like her mother, she would also die from effects of radiation exposure.

Despite her success, Marie Curie repeatedly encountered opposition from French male scientists, and she did not acquire financial gains from her research and discoveries, in part because she and Pierre had declined to patent their discoveries. Curie never regretted her decision, saying that radium was an element, and as such, belonged to the people. She was clear that scientific research had value in its contributions to mankind, not in monetary benefits.