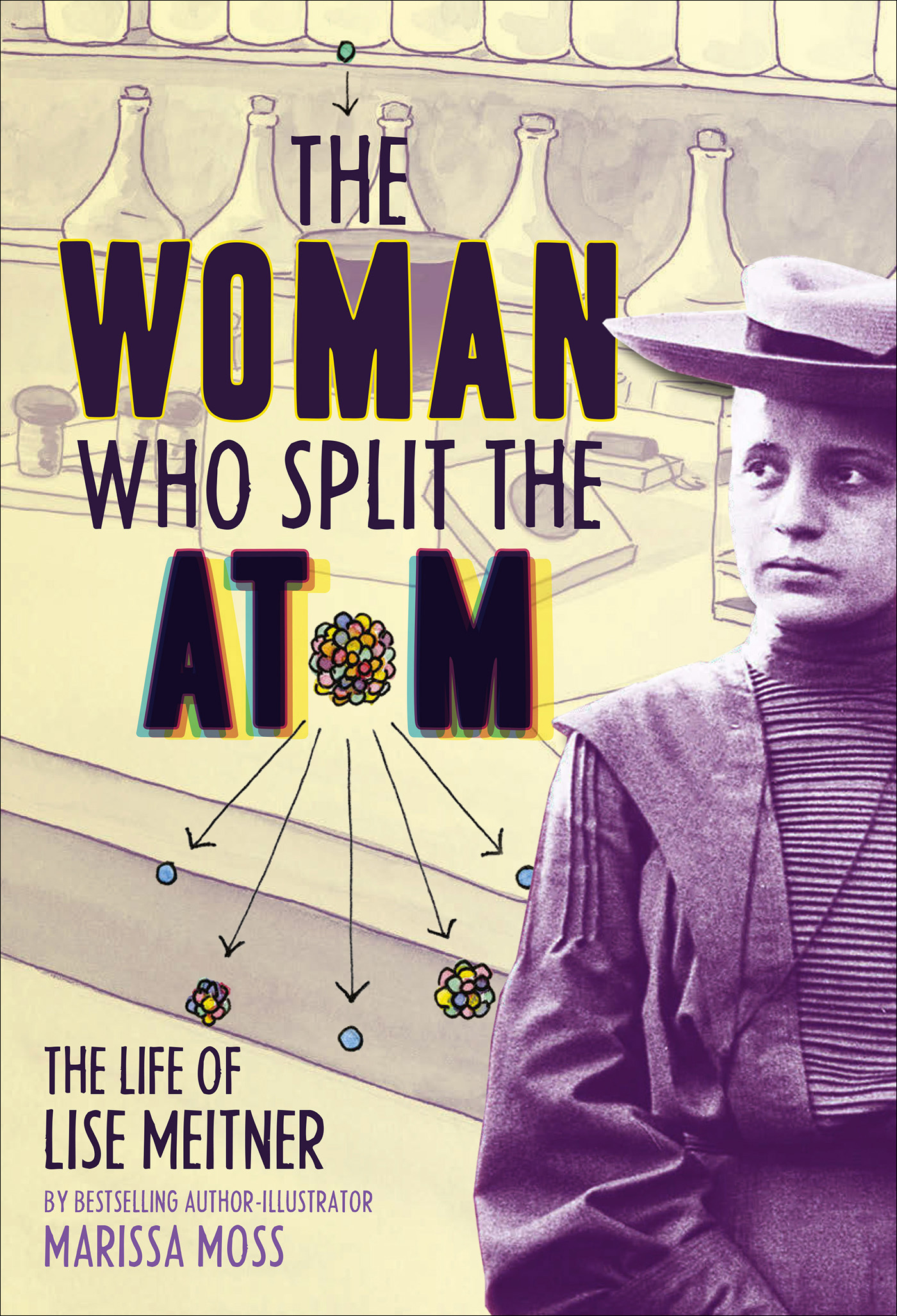

The illustrations in this book were made with pen, ink, and watercolor wash.

See for photography credits.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for and may be obtained from the Library of Congress.

Edited by Howard W. Reeves

Published in 2022 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, an imprint of ABRAMS.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Abrams Books for Young Readers are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

TO WARREN HECKROTTE,

with deep gratitude for his help in understanding nuclear physics. Warren was a nuclear physicist who worked at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and was involved in nuclear weapons talks with the Soviets under five different presidents, starting with John F. Kennedy, ending with Bill Clinton. Warren knew personally many of the physicists mentioned in this book and gave me access to his personal library of books and documents about the history of nuclear fission. Sadly, Warren died before the manuscript was finished, but we spent many hours together at his dining room table, hashing through different aspects of Meitners story and the science and personalities behind it.

CONTENTS

ONE

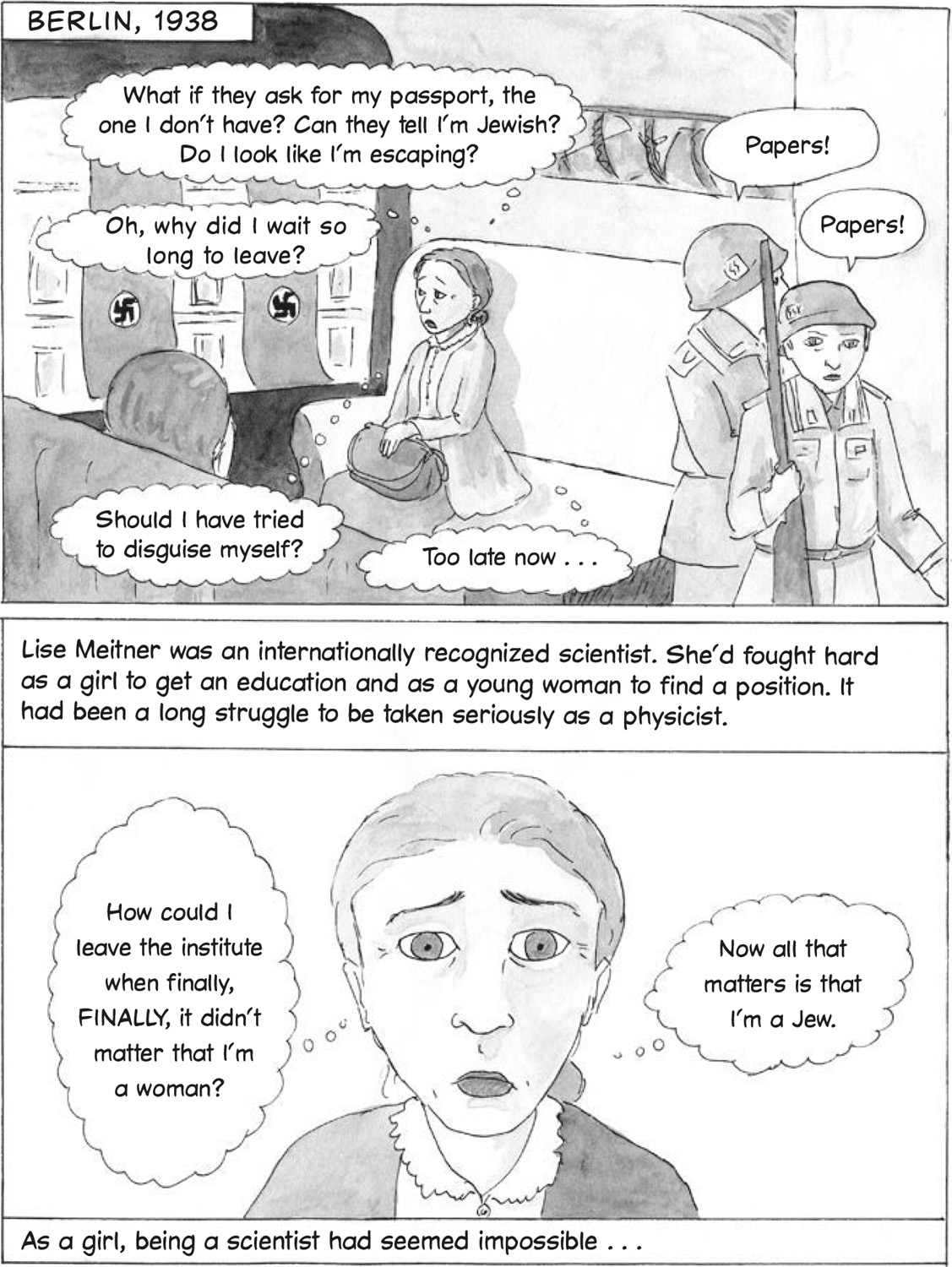

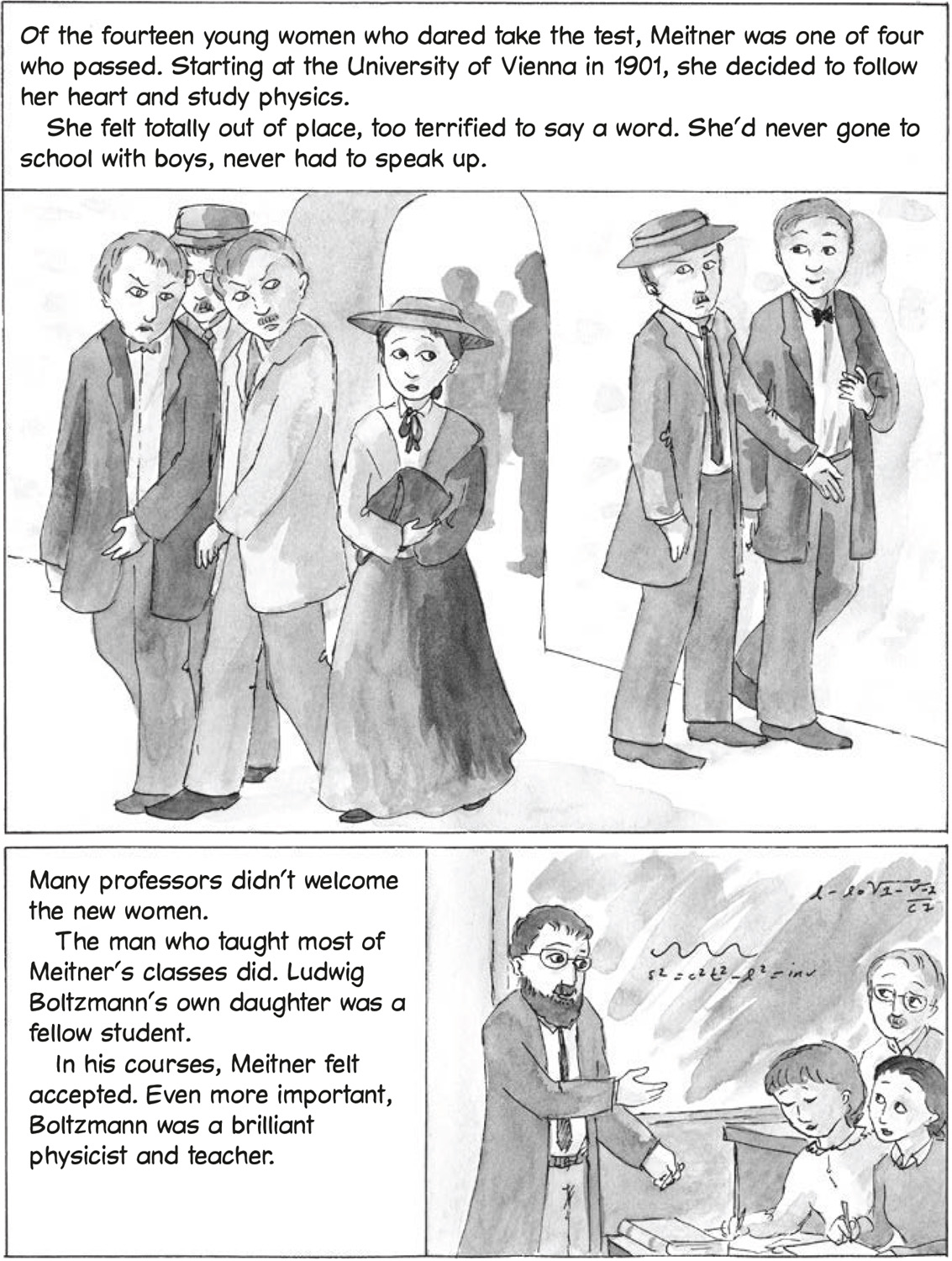

DREAMS OF THE IMPOSSIBLE

Lise Meitner had thought of herself as a completely ordinary little girl, a girl who happened to sleep with a math book under her pillow, as if the equations would slip into her head overnight. Instead of reading novels or poetry like her sisters, she read about the quadratic formula, about figuring out the volume of a cone, about plotting a parabola on a grid. Her brain was full of questions, and she had to know the answers.

Her parents encouraged her curiosity. They wanted all eight of their children to think about the world and follow their interests. For them, the late 1800s were exciting years to be in Vienna. Meitners mother had come from Russia, her father from Czechoslovakia. Both were places where Jews couldnt live, work, or study easily. In Austria, Jews may have lived in ghettos, but new doors were open to them. Meitners father was one of the first Jews to become a lawyer in this more accepting world.

More accepting for Jewish men, at least. Going to college, following a profession, that was for sons, not daughters.

Still, Meitner learned however she could. She studied the colors in a drop of oil. She noticed the reflections in puddles. She couldnt stop herself from asking questions about how the world worked. What made the film on the top of the puddle? How did light reflect off it? How could a drop of water be divided? What kept the drop together in the first place? She was excited that there were such things to find out about in our world, she wrote later when thinking about her childhood.

To get the answers, Meitner wanted to go to high school. This was something girls simply didnt do in most of Europe in the late nineteenth century. Why bother to teach girls anything when they only needed to know how to raise children and run a household? In Vienna, not only were girls considered incapable of learning, but their presence would be a distraction for the boys. The University of Vienna declared that the character of the university would be lost and the institution endangered by their [womens] presence.

Meitner didnt think she would distract anyone. Nobody would ever call her pretty. Not that she cared about that, since she didnt want a husband anyway. She just wanted to learn the way her brothers did.

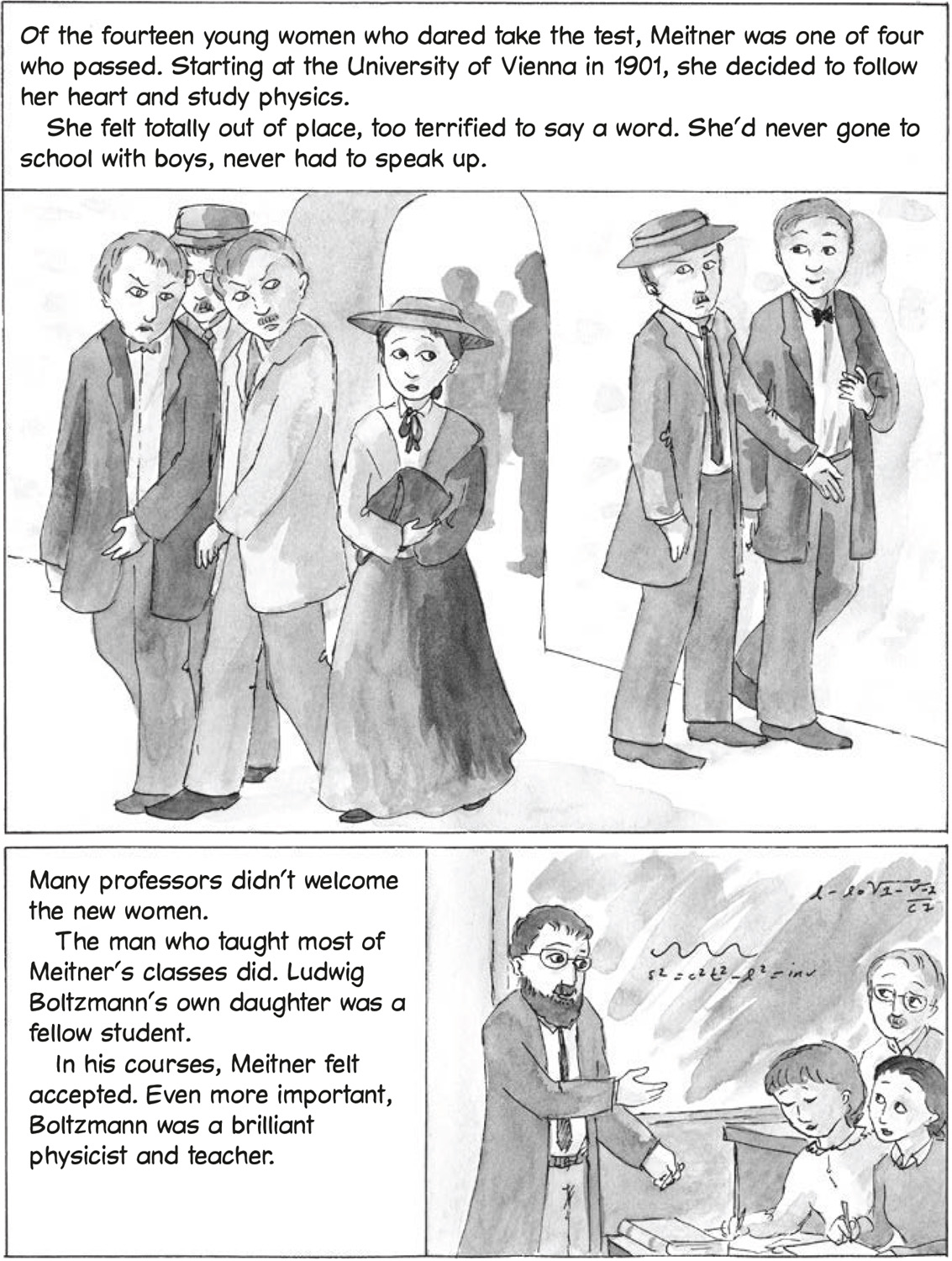

Meitners parents encouraged her. Her mother urged her to study on her own, saying, Listen to your father and me, but think for yourself. Her father used himself as an example for his daughter, saying that if he could become a lawyer, then she could learn whatever she wanted. And like her father, she was lucky. In 1897, when Meitner was nineteen, the law in Austria changed and women were allowed to go to universities. But first they had to pass the difficult high school exit examwithout having actually gone to high school.

Her older sister Gisela started preparing for the test first, but Meitner quickly joined her. They studied Greek, Latin, math, physics, botany, zoology, mineralogy, psychology, logic, literature, and history. They read constantly, from as soon as they opened their eyes in the morning until they closed them, exhausted, at night. Meitners younger brothers and sisters teased her that she would fail because youve just walked across the room without picking up a book. Meitner was obsessive. This was her chance, and she wasnt going to miss it.

Gisela passed the difficult exam first and started medical school. As Meitner finished her studies, her father discouraged his younger daughter from following the same pathhaving two daughters in the impossibly male field of medicine was too much. Medicine wasnt Meitners passion anyway. Physics was. She wanted to figure out how the world worked, but she didnt think physics had any practical applications. Medicine seemed the more noble, useful thing to do.

So it was a relief when Meitners father urged her to follow her real interest. He knew any profession would be difficult for a young woman. To face the many obstacles, you had to care deeply about your subject, be willing to fight constantly for your right to be in that field. The tough high school exit exam was only the first hurdle.

TWO

EDUCATION AT LAST!

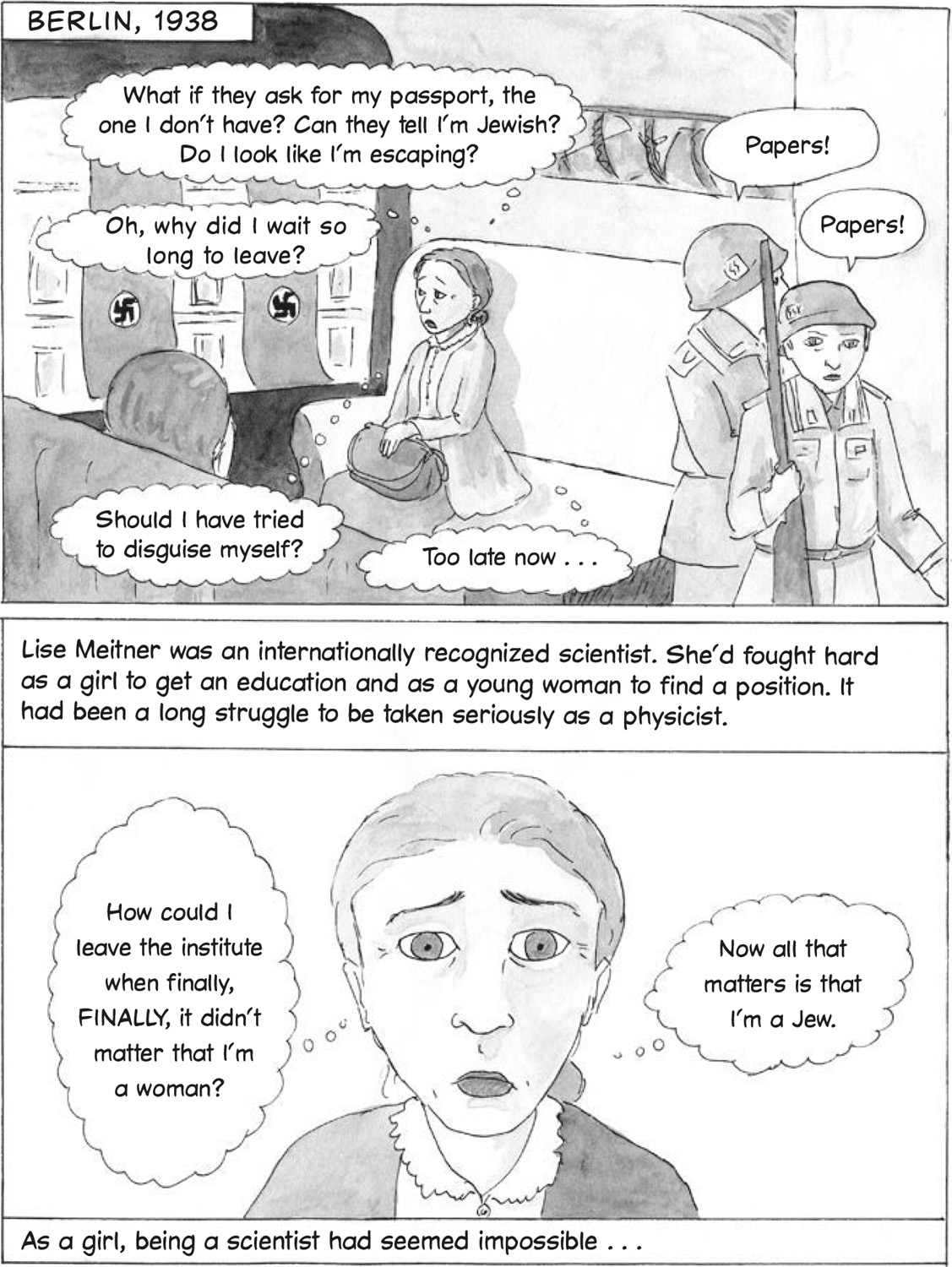

Meitner called Boltzmanns lectures the most beautiful and stimulating that I have ever heard... He himself was so enthusiastic about everything he taught us that one left every lecture with the feeling that a completely new and wonderful world had been revealed. Boltzmanns big bushy beard shook as he spoke, his thundering voice commanding his students attention. And what he taught was fascinating. Boltzmann was an early believer in atoms, which many established physicists mocked. Could you see an atom? How could you believe in something that was invisible? The controversy Boltzmann described made clear to Meitner that science pretended to be objective but was often shaped by human bias. Meitner wanted to follow Boltzmanns pathshe was hungry to discover what she didnt know, not look for confirmation of how she wanted things to be.