THE AMAZING

STORY OF

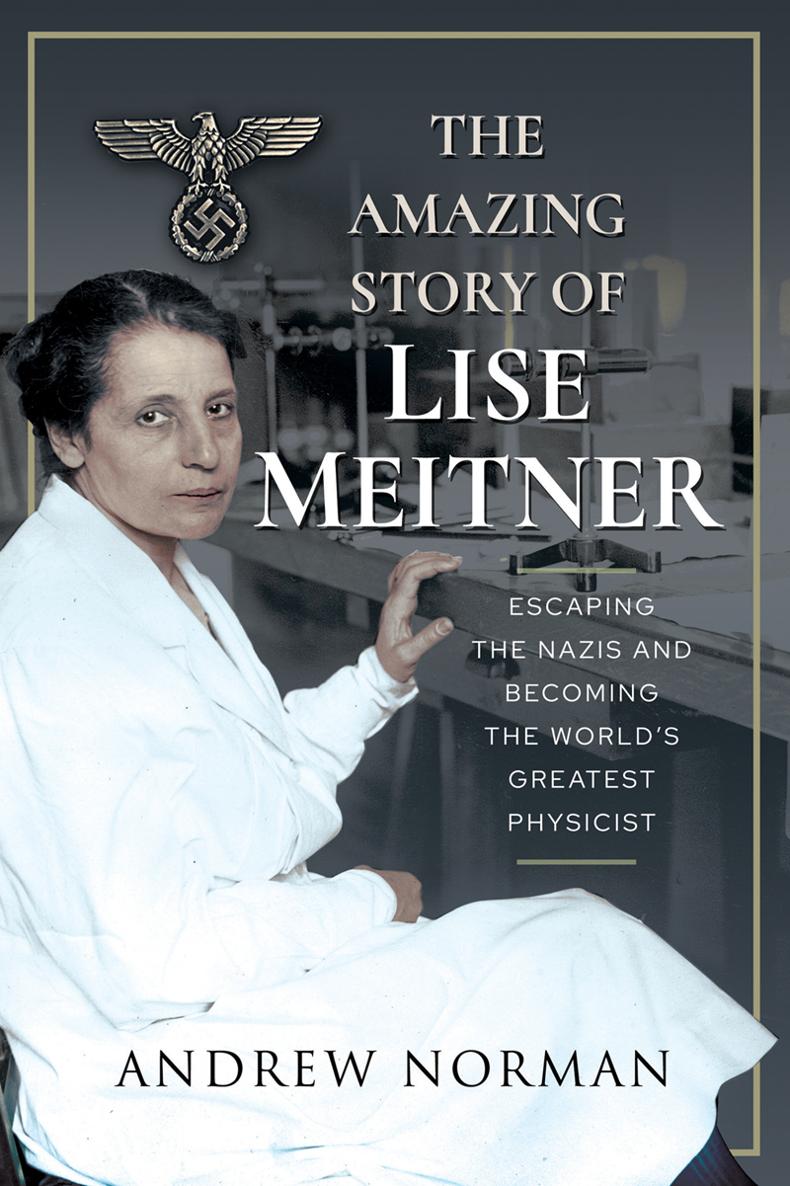

LISE

MEITNER

Escaping the Nazis and Becoming the Worlds Greatest Physicist

To

Ruth Lewin Sime

in gratitude

THE AMAZING

STORY OF

LISE

MEITNER

Escaping the Nazis and Becoming the Worlds Greatest Physicist

ANDREW NORMAN

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Andrew Norman, 2021

ISBN 978 1 39900 629 3

eISBN 978 1 39900 631 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 39900 632 3

The right of Andrew Norman to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Ruth Lewin Sime for her kindness, generosity, and expertise; Philip and Anne Meitner for welcoming me into their home, sharing memories, and permitting me to use material from the Churchill College Archives; Bernard C. Burgess for help with translations and research; Anthea J. Coster and Arina R. Klokke for providing information about their grandfather Dirk Coster, and to Arinas husband Eelco M. Havik; Karl Grandin; Helen Fry; and Anthony Barrett.

I am grateful to Robert Pugh, Barry L. King, Tom Topol, the Reverend John Lenton, Allen Packwood, and Susanne Uebele.

I also thank Churchill College Archives, Cambridge, UK; University of Chicago Library; Rijksmuseum Boerhaave Museum Archives, Leiden, Netherlands; and the Archive of the Max Planck Society, Berlin-Dahlem. Letters quoted in the text were, in the main, translated by Ulla McDaniel, Eleonore Watrous, Bernard C. Burgess, Rachel Norman, and Eelco Havik.

I am deeply grateful to my beloved wife, Rachel, for all her help and support.

Introduction

In May 1993, US physics historian Margaret W. Rossiter coined the term the Matilda effect.

Although womans scientific education has been grossly neglected, said Matilda, yet some of the most important inventions of the world are due to her. A woman, she said, has to face contempt of her sex, open and covert scorn of womanhood, and deprecatory allusions to her intellectual powers. In the case of inventions by women, and Matilda listed some of the more major ones, she would hold no right, title, or power over this work of her own brain.

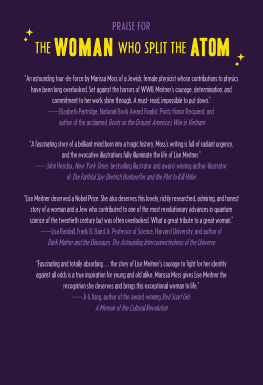

Sixty-three years later, on 10 December 1946, a woman physicist, whom German-born theoretical physicist Professor Albert Einstein (18791955) described as even more talented than Marie Curie herself, would find herself a victim of such discrimination when her one-time colleague, Otto Hahn, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics. The third member of the team of Berlin researchers who Fritz Strassmann, the second member of the team, described as the intellectual leader of our team, was ignored. Her name was Lise Meitner.

Foreword

Lise Meitner was born in Vienna, Austria on 7 November 1878. She was petite in stature and, from a young age, passionately interested in science. Subsequently, she was determined to make this her career, but events were stacked against her from the start. For girls, unlike boys, state education ended at the age of 14, and, in any event, women were debarred from university education.

The breakthrough came when the Austrian government relaxed its regulations and permitted women to enrol as undergraduates. For Lise, this came only just in time, and she managed to master the preparatory school curriculum by cramming seven years of study into two and passing the qualifying examination or Matura to enter the university. However, having obtained her degree from the University of Vienna, she found it impossible to obtain a professional post and, accordingly, moved to Berlin where she worked as an unpaid laboratory assistant. Finally, in 1917 at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (KWIC) in Berlins borough of Dahlem, her talents were recognised, and she was appointed head of physics with her own physics department. (This is not to be confused with the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (KWIP), Dahlem, which shared the same campus.)

In 1938 there came another setback when Lise, on account of her being an ethnic Jew, was forced to leave Nazi Germany. Lise was not a practising Jew, for she and her siblings had been left to choose their own faith, and in 1908 she had become a Protestant (in a Catholic country), although she was not particularly religious. She, therefore, relocated to Sweden. However, she kept in contact with her fellow researchers in Berlin.

The heaviest known element at the time was uranium, and Lise was fascinated by the results that others had achieved by bombarding (i.e. irradiating) it with neutrons. In 1934, she persuaded Otto Hahn, the head of the KWIC, to join her in a uranium investigation. The outcome was that her team of three, comprising herself and two chemists, Hahn and Strassmann, came up with some extraordinary results which they were at a loss to explain.