Copyright 2020 by 11th Street Productions, LLC

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bascomb, Neal, author.

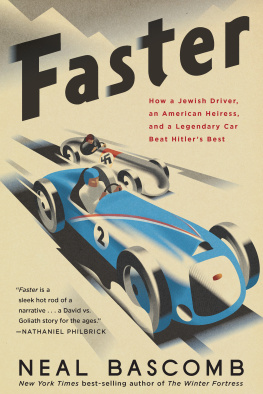

Title: Faster : how a Jewish driver, an American heiress, and a legendary car beat Hitlers best / Neal Bascomb.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019033972 (print) | LCCN 2019033973 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328489876 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781328489838 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Automobile racingHistory. | Automobile racing driversBiography. | Discrimination in sports. | Grand Prix racingHistory. | World War, 19391945Social aspects.

Classification: LCC GV1029.15 .B347 2020 (print) | LCC GV1029.15 (ebook) | DDC 796.7209dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019033972

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019033973

Cover illustration Mads Berg

Author photograph Meryl Schenker Photography

v1.0220

For Charlotte and Julia,

May you embrace lifes fearful joys

I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips,

Straining upon the start.

William Shakespeare, Henry V

Authors Note

A TERRIFIC ADVENTURE AWAITS , but I must hurry.

Midmorning, heading north on the I-405 from Los Angeles International Airport, I am stuck in a traffic jam. A sea of vehicles of every make surround me: long-haul semis, boxy sedans, Denalis with tinted windows, Priuses with Uber stickers, black town cars, landscaping trucks, and the occasional zesty convertible. My own rented black GMC Terrain is one of those nondescript compact SUVs that automakers stamp out with all the cookie-cutter variation of a Ford Model T. If parked in a crowded lot, I would fail to pick out my rental without clicking its key fob to trigger the lights.

None of us is getting anywhere fast. Ten minutes pass at a standstill. Then twenty. According to Google Maps, I have another fifty-eight milesor one hour, fifty-two minutesto go until I reach Oxnard. The line of my route on the screen map looks an ugly red. Surely they will wait for me before they ship the Delahaye 145 race car off to London to sit behind a velvet rope in the Victoria & Albert Museum. I try not to pound the steering wheel in frustration.

The bottleneck ahead finally loosens. Once I veer off onto the I-10 toward Santa Monica, the stop-and-go traffic becomes mostly go. Then I am cruising north on the Pacific Coast Highway. In the distance there are mostly vistas of ocean and wildflower-covered hillsides. I might make it after all.

My GMC is comfortable, but unexcitinga rental car obligation. Retractable seats with good lumbar support. Automatic transmission. Apple CarPlay to listen to my latest Spotify favorite, the Lumineers. Past Malibu, I battle with the electronic windows, unable to convince them to remain half open. Instead I seal myself into the air-conditioned cocoon. No salty breezes for me. At stoplights, the engine shuts off to save gas. It does not ask me for permission.

Halfway there I take a call from my wife in Seattle. She cannot even tell Im driving. Whatever churns underneath the hood, it is quiet, reasonable, and unflappable, all worthy qualities in a vehicle meant to get one safely from point A to point B.

A very different car is being readied for me in Oxnard. It is a rewardand capstoneafter two years of investigation into its long-forgotten history.

There was a period, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, when the Delahaye 145 was one of the most noted Grand Prix race cars in the world. Its exploits had equal billing to news stories of peace coming undone in Europe. Huge crowds assembled to watch it compete or to glimpse its shiny V12 engine up close at motor shows. When it first appeared at Montlhry, an autodrome in France, many thought its design peculiar. One critic likened it to a praying mantis rather than a machine built for speed. After the Delahaye smashed records on the closed oval circuit, sought the Million Franc prize, and dared to be The Car That Beat Hitler, the naysayers became adoring admirers. Its owner, its designer and builder, and the driver who often risked death pushing the Delahaye to the limit were heralded as national heroes.

Its story began in 1933, when the leader of the new Third Reich made reigning over the Grand Prix one of his first missions. His Silver Arrow race cars, piloted by the ruthlessly indefatigable champion Rudi Caracciola and the blond-haired, blue-eyed poster boy Bernd Rosemeyer, stood for more than sporting prowess: they represented the master race conquering the rest of the world. A Mercedes-Benz victory is a German victory, heralded the Nazi propaganda machine. Hitler aimed to use their success to inspire hundreds of thousands of young men to enlist in the ranks of a motorized army, which its automobile firms, now transitioning into massive industrial machines, would help bring into being.

After years of unchecked German triumph, a woman called Lucy OReilly Schell decided that something must be done, so she launched her own Grand Prix racing team. A dazzlingly fine driver in her own right and the only child of a well-heeled American entrepreneur, she had cash to spend, reasons of her own to challenge the Germans, and the will to claim her place in a world dominated by men. For a car, she chose the most unlikely of manufacturers: Delahaye. Managed by Charles Weif-fenbach, the old French firm was known for producing sturdy, staid vehicles, mostly trucks. Racing was a path to save the small company. For a driver, Lucy recruited Ren Dreyfus; once a meteoric up-and-comer, he had been excluded from competing on the best teams, with the best cars, because of his Jewish heritage. Triumph over the Nazis promised redemption for all of them.

My journey to uncover this tale of a team of strivers took me in many directions. Unlike the prewar stories of such sports giants as Jesse Owens, Joe Louis, or that crooked-leg racehorse named Seabiscuit, time had largely erased from memory the endeavors of Lucy, Ren, Charles, and the Delahaye 145. No writer had devoted a book solely to the subject. At first, I sank myself into libraries like the marvelous Revs Institute in Naples, Florida. This was my first foray into automotive history, and the sheer volume of contemporaneous journals and magazines devoted to the Grand Prixin multiple languagesstunned me. Day after day, I thumbed through thousands of pages, rooting out pieces of the saga. The Daimler-Benz Archives in Stuttgart and the National Library of France in Paris proved equally helpful.

I quickly learned that information on classic carsand their driversis deeply cherished but often held closely by clubs and private collectors. Diligence and a little bit of persuasion gained me access to scholarly treasures held inside a sprawling French farmhouse, a cluttered Seattle garage, and a storybook English manor, among other places. The family of Ren Dreyfus shed a lot of light as well.

It is one thing to study detailed course maps of the significant races in this history. It is another to walk or drive them. La Turbie outside Nice. The Nrburgring in the Eifel Mountains. Montlhry south of Paris. Monaco through the streets of Monte Carlo. Pau on the edge of the Pyrenees separating Spain and France. I wanted to know every hairpin, every straight, every rise and fall.

Throughout my research, I visited numerous car museums across America and Europe, wandering among the collections of Alfa Romeos, Bugattis, Maseratis, Delahayes, Talbots, Ferraris, Mercedes, Peugeots, and Fords. Polished to a sheen, these cars looked like works of art. And they were immobile, surrounded by walls, their purposeto go fastthwarted now.