In memory of Alan Henry (19472016),

colleague and friend

The potential biographies of those who die young possess the mystic dignity of a headless statue, the poetry of enigmatic passages in an unfinished or mutilated manuscript, unburdened with contrived or banal endings.

ANTHONY POWELL , The Valley of Bones

Typical of Drax to buy a Mercedes. There was something ruthless and majestic about the cars, he decided, remembering the years from 1934 to 1939 when they had completely dominated the Grand Prix scene... Bond recalled some of their famous drivers, Caracciola, Lang, Seaman, Brauchitsch, and the days when he had seen them drifting the fast sweeping bends of Tripoli at 190, or screaming along the tree-lined straight at Berne with the Auto Unions on their tails.

IAN FLEMING , Moonraker

PROLOGUE

He could see the umbrellas going up again in the grandstands as the rain fell harder, water sluicing across the track, in places forming inch-deep, foot-wide rivers, elsewhere creating a smooth surface as deceptive as ice. The Grand Prix was past the halfway point and he had made it through to the lead.

On a filthy afternoon in the Ardennes, the conditions were as treacherous as they had been when he made his first tentative steps into the sport eight years earlier, barely out of school uniform. But there had been no crowd to speak of on that sodden day in the Malvern Hills, no one to see the 18-year-old make a beginners mistake. There had been no team manager to offer guidance, no mechanics attending to his car, no young wife watching from the pits, and certainly no national prestige at stake.

No driver likes racing in the rain. Some good ones, champions in other circumstances, cant cope with it. They ease back and wait for the day to be over. Others have a sensitivity that allows them to make the most of the challenge: a light touch on the steering and the throttle, and even greater delicacy on the brakes. In his early days he had made mistakes in the rain, but he had learnt from them and now he was regarded as one of those who possessed the special instinct.

Several of his rivals had already spun off the track and out of the race. His nearest challenger was twenty seconds adrift. He could afford to back off a little and reduce the risk as he sped along the tree-lined road, but that was not in his mind. He still needed to prove himself. His only thought was to press on in the gloom, peering through his visor for reference points a farmhouse, a road sign, the end of a line of trees and feeling his tyres search for grip on the wet asphalt. The rain mantling the hills and forests in this corner of Belgium was unlikely to lift in the final hour of the race. As he approached the end of the twenty-second lap, with thirteen to go to the chequered flag, it was all in his hands.

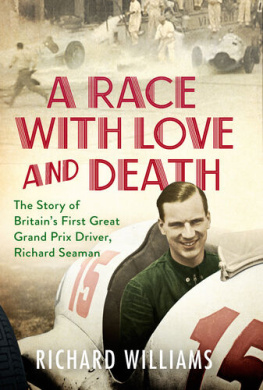

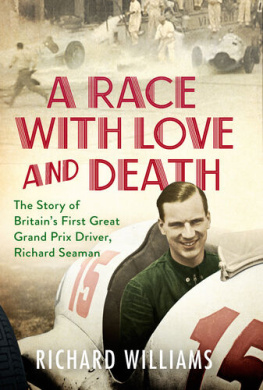

When Dick Seaman died while leading the Belgian Grand Prix that day in 1939, at the age of twenty-six, he was on the brink of taking his place among a generation of British sporting heroes. The others were not hard to identify. Fred Perry, the Stockport-born son of a cotton spinner, became the mens singles champion at Wimbledon three years in a row, from 1934 to 1936, between the ages of twenty-five and twenty-seven. The Russian-born Prince Alexander Obolensky, whose father had been an officer in the Tsars Imperial Guard, was nineteen when he ran three-quarters of the length of Twickenham one afternoon in 1936 to touch down for an unforgettable try in Englands first-ever rugby victory over New Zealand. In 1937 the 21-year-old Stanley Matthews, the wizard of the dribble, scored a hat-trick in Englands 5-4 defeat of the formidable Czechoslovaks at White Hart Lane. And in the Ashes series of 1938 the Yorkshire cricketer Len Hutton, aged twenty-two, spent thirteen hours compiling a record 364 runs against Australia at the Oval. Given another season or two, Seaman would surely have joined them.

And yet, five days after his death, the biggest wreath at his funeral came from Adolf Hitler, whose colours he had carried in races across three continents. When he crashed in his Mercedes-Benz, he was admired as the first British racing driver to join one of the two state-sponsored German teams that had established a total domination of the sport. He had emerged from a background of privilege and sophistication, but all his parentswealth would have been useless without talent and determination as he fought his way to the top.

As the mourners gathered in London, they were headed by the two women between whom he had been forced to choose barely six months earlier: his mother and his wife, united in grief but severed from each other in every other way. And many of those present were shocked by the arrival of the wreath from Berlin. Like Dicks half-hearted Hitler salute at the Nrburgring a year earlier, a reluctant response to the acclaim of a German crowd while surrounded by Nazi uniforms on the victory podium at the moment of his greatest triumph, it stained the reputation of a young man who had now lost the chance to explain himself. Unlike a Hutton or a Matthews, he would have no opportunity to pick up the threads of his sporting career once the war was over. Or, more important, to show which side he was really on.

PART ONE

191130

A Mayfair romance

The couple who would become Dick Seamans parents met on a November evening in 1910 at the restaurant of the Savoy Hotel, overlooking the Thames by Waterloo Bridge. William Seaman and Lilian Pearce were the guests of Sir Thomas Dewar, a Scottish whisky distiller and former Member of Parliament. On this evening Tommy Dewar was hosting a table of ten at an establishment where the culinary standards had been set by Auguste Escoffier and diners were expected to wear evening dress.

He was also acting in the role of matchmaker to two friends who had not met before: a man and a woman who had both been widowed prematurely, and whom he seated together. William John Seaman fifty-two years old, a tall and distinguished figure, albeit bearing some of the signs of recent ill health was a director of John Dewar & Sons. Seven years earlier his wife had died at their home in Glasgow, leaving him with a 10-year-old daughter. His neighbour at the dinner table, the vivacious Lilian Graham Pearce, was around twenty years his junior; she had lost her husband, a former officer in the Manchester Regiment, to a sudden illness in 1902, barely a year after their marriage. She, too, had been left with a daughter, then still an infant. As she wrote in a memoir many years later, she liked the look of William Seaman straight away, finding him charming and interesting as he told her that he had recently spent several months convalescing on his yacht off the west coast of Scotland after treatment for severe heart problems. Now he was staying briefly in London, at the Berkeley Hotel on Piccadilly, en route to Bournemouth, where he planned to continue his recovery in the company of his valet and his personal physician. Her home, she mentioned, was in Clarges Street in Mayfair, only a couple of minutes walk from his hotel.

After dinner the party moved on to the Savoy Theatre, where William Seaman thwarted Tommy Dewars plan to reshuffle his guests by slipping quickly into the seat next to Mrs Graham Pearce. They continued their conversation during the intervals, and he invited her to lunch at the Ritz the following day. When she told him that, alas, a womens lunch party at her club meant she would have to decline, he grimaced and invited her to reconsider, pointing out that it would be his last day in London. He leaned back and put his hand on his heart, leading her to imagine that he might be about to have another heart attack. While protesting that she hated to break an appointment, she finally accepted his invitation and was interested to note the colour return to his cheeks. Their host noticed it, too. I asked you to engage this man in interesting conversation, Tommy Dewar told her, not to give him a charge of electricity.